An exclusive preview of the Designers’ Notes for the upcoming The Fate of All.

Remember, only the most audacious of feats find the favour of the mighty Gods. Take your place in Krateros’ Phalanx by sending a votive tablet to info@TRLGames.com , and write your name in history! Or visit the following Temple to know more about the future: https://trlgames.com/the-fate-of-all

Designer’s Notes, by Fabrizio Vianello

The Classical Antiquity period has always been my other great passion, and I’ve been planning a series about it since the first days of Thin Red Line Games.

As already happened for the NATO – Warsaw Pact conflict, I was quite confident and full of Hubris when I’ve started, and once again I’ve discovered rather quickly how inadequate my knowledge was and how naive some of my opinions were. With that in mind, I think the best possible use for these Designer’s Notes is to share some of our discoveries, and how they have been used and integrated in The Fate of All.

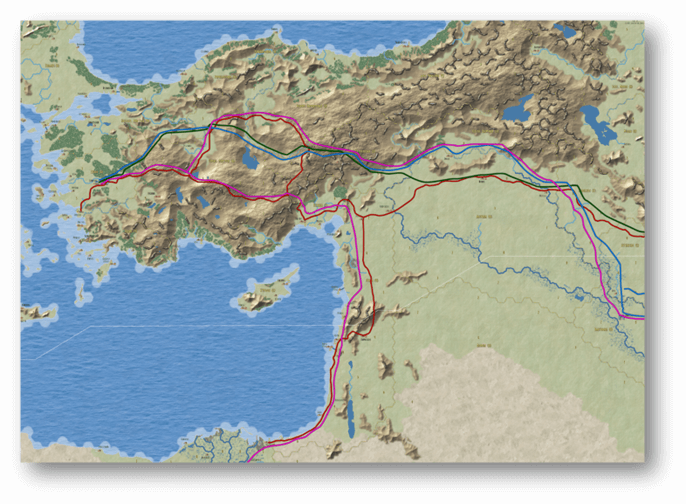

The Geography of Herodotus, Updated Version

The initial map layout has been prepared using 1:500,000 charts printed by the British War Office and Air Ministry in the 1950 – 1957 period, as they represented the areas before the significant changes introduced by heavy industrialisation and petrodollars.

After defining the basics, several changes have been made to reflect the layout in the IV Century BCE:

-

The areas covered by forest have been increased by 20 – 25%.

-

The coastline has been slightly but significantly changed, particularly around Lamia, Ephesos, Mallos, and Tyros.

-

Some natural lakes not existing anymore have been added, and several artificial lakes have been removed.

The most difficult task has been identifying and cataloguing the cities, as we needed to evaluate not only their existence, but also their supply and defence capabilities, both key factors during the campaigns of Alexander.

In some cases, the location and extension of a city remained uncertain despite our best effort. One example for all is Thapsakos on the Euphrates (hex B1820), that could have been placed in at least two different locations, depending on who you are listening to.

Tracing the Persian Royal Road, probably the first serious attempt to build a road network encompassing a vast empire, was also difficult. Nothing certain is known about its extension or path, except for a couple of segments explicitly cited in the ancient sources. The fact that there’s no significant archaeological evidence also suggests that the overall quality of the Royal Road was not comparable to the Roman ones, but nevertheless it had an impact on movement that cannot be ignored.

Last but not least, a decision has to be taken about bridges. Here too, the scarcity of archaeological evidence suggests that permanent bridges were not commonplace, and that the few existing ones were probably not suitable for military use.

Different theories about the Royal Road

The Marching Army

Several ancient sources and modern researches gave us a quite detailed idea of the average movement rate of an army. Here are some examples of documented marches during the campaign:

| From → To | Army Size | Distance | Days |

| Therme → Sestos | 35k | 480 km | 20 |

| Sardeis → Ephesos | 50k | 130 km | 4 |

| Tyros → Gaza | 40k – 50k | 220 km | 9 – 11 |

| Gaza → Pelousion | 40k – 50k | 150 km | 7 |

| Darius’ Tigris Crossing | 100k? | 5 – 6 | |

| Alexander’s Euphrates Crossing | 50k | 5 |

In the end, the good old average figure of 25 – 30 km per day can be used as a basis, but other considerations must be taken into account: The terrain, the size of the army, and the presence of significantly slower elements in it.

Terrain does not reserve big surprises, as it works more or less in the same way no matter the era, so I will leave it aside for the moment.

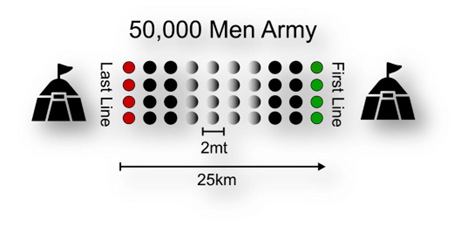

The Bigger, the Better?

The size of the army is a more interesting point. Of course, the bigger the army, the slower it moves. Some of the reasons for that are immediately clear, like the increased quantity of supply and beasts of burden, but there are others not that evident.

Let’s take as an example the typical army led by Alexander, consisting of approximately 50,000 men. Using lines of 4 men, probably the maximum allowed considering the roads and trails available at the time, the column will have 12,500 lines. With each line taking on average 2 meters, the army will form a column 25 km long.

This means that when the march starts and the second line of 4 men moves out, the first line will be two meters ahead….OK, no big deal. But when the 2500th line moves out, the first line will be already 5,000 meters ahead. In the end, the 12,500th line will move out from the base camp only when the first line has already marched for five hours and has arrived at destination, 25 km ahead.

Bottom line: if your army is significantly bigger than 50,000 men a part of it would reach the destination camp only the following day, making a 25km per day marching rate highly improbable if not impossible.

A possible solution, both in real life and here, is splitting the army in different columns, each one marching independently. This could bring different problems such as the availability of an alternate route, the possibility for a part of the army to be attacked while separate from the rest, and difficult coordination among the columns.

Those Beasts Are a Burden

Baggage and siege trains are two additional factors that can slow down the pace of an army. These involve a considerable number of draft animals, recognised for their endurance rather than speed, and may incorporate wagons as well.

Moreover, baggage trains could include not only food and equipment, but also servants, women, and loot. The more, the worse.

Philip II of Macedonia was well aware of the negative impact of an oversized baggage train, and established rules for it: horses and mules were the only beasts of burden allowed, and wagons were forbidden. Moreover, the number of servants following the army was limited to one for every ten foot soldiers, and one for every cavalryman. And of course, no women.

Alexander followed the same rules as long as possible, abandoning them only when he started advancing in Mesopotamia. Even after that, he always tried to keep the size of the baggage train under control, and before entering the Kara-Kum desert he ordered to burn all the excess baggage and wagons, beginning with his own.

As already stated in the rules, in The Fate of All every army is considered to have its “standard” baggage train. When the army is particularly big, as it is often the case for the Persians, or an inhospitable area had to be crossed, the only solution can be increasing the size of the baggage train, thus slowing down the march rate.

No Food, No Babylon

Alexander, Caesar and Napoleon all had something in common, beside military genius: They understood the utmost importance of logistic, and planned accordingly…At least most of the times.

Despite these examples, you may be tempted to examine the map and conceive your plan with only a cursory look at the supply problems. After all, how difficult could it be, right?

Well, not here. If you don’t plan accordingly, your will probably find yourself in the middle of nowhere with only some carrots to eat, and the survivors of your army ready to sacrifice you to appease Zeus.

The hard facts to take into account are:

-

The first and foremost source of supply for an army was foraging, also known as “living off the land”. This means that the available supply depended on the season.

-

Even in the most fertile areas, the territory in classical antiquity had not enough resources to feed an army of tens of thousand men and horses for more than a couple of months.

-

Alternative sources of provisions costed money, in case of paid requisitions, or the support of local governors and population in case of plundering.

The problems don’t end here, but there’s also some solution. Let’s dig in some additional detail.

Beverages Not Included

We need some math now, please bear with me.

According to “The Logistic of the Macedonian Army”, one of the most cited studies on the subject, Alexander’s army at the beginning of the campaign consisted in 48,000 soldiers, 6,000 cavalry horses, 16,000 slaves and adjutants, plus 1300 pack animals for carrying tents, blankets, personal possessions and so on.

When marching through terrain with abundant water and forage for the animals, the total weight of grain requirement of the personnel, horses, and pack animals was 269,000 lb. Each day.

A pack animal could carry 250 lb, but needs 10 lb of grain daily, plus 10 lb of forage that could be hopefully found by pasturing in the fields.

Therefore, the number of pack animals required to carry one day’s supply was 1,121. That’s 269,000 lb (the total of grain needed) divided by 240 (the 250 lb carrying capacity of a pack animal minus its daily ration of 10 lb).

Using the same formula, we can find the number of pack animals needed to transport the army’s provisions for several days:

| Days | Grain Needed (lb) |

Carry Capacity (250 – 10 lb per day) |

Animals Needed (Grain / Capacity) |

|

1 |

269,000 |

240 |

1,121 |

|

5 |

1,345,000 |

200 |

6,725 |

|

10 |

2,690,000 |

150 |

17,934 |

|

15 |

4,035,000 |

100 |

40,350 |

|

20 |

5,380,000 |

50 |

107,600 |

As you can see, it was practically impossible to carry more than a few days’ provisions, even in optimal conditions (remember, water and forage are not included). Moreover, as the author of the study Donald Engels noted, “it is doubtful whether this many suitable animals existed in the whole of Greece”.

A smaller army will have of course lower needs, but also fewer men to handle the pack animals, so the overall problem doesn’t change much.

A realistic and already generous upper limit was probably 5 – 6 days of provisions carried and constantly replenished during march, and this is the number used by the supply rules. Every 10 movement points, a moving army has eaten up the supply initially transported and must replenish it by whatever source available: Foraging in the regions crossed, requisitions in friendly cities, food loaded on the fleet, sea shipping to friendly ports, or plunder as a last resort. If the provisions gathered are scarce, things will take a bad turn rather quickly.

This is also why it doesn’t really make a difference if you just left the valley of Eden when entering the valley of Tears: no matter how plentiful the previous region was, the army can transport only a few days’ supply and needs to find the rest in the area where it spent most of the time.

Your New Best Friend: Light Cavalry

The first solution to the supply problems was light cavalry. Cavalry foraging parties moved ahead and on the flanks of the army, finding and collecting provisions, crops, cattle, drinkable water, anything. An army with a strong cavalry component could have been able to cross an otherwise inaccessible region and survive, at least for some time.

Foraging was not a job without risks, as an army having cavalry to spare would have used it to attack and raid the enemy foraging parties. Depending by the orders, a cavalry detachment could have covered both roles at the same time.

In The Fate of All, light cavalry is used exactly in the same way, and it is up to the army commander to assign it to foraging, raiding, or both.

An Unexpected Help: Forced March

We are all used to the idea that forced marching increases the distance covered by an army in a given time. However, during Classical Antiquity, it was frequently employed not just to increase distance but mainly to minimise the time spent in areas with limited supplies.

By crossing a barren region as quickly as possible, the army could avoid depleting its transported provisions, and reach a more fertile area before they are all eaten up.

Alexander was a specialist on this kind of forced marching and used it when crossing the central mountains of Anatolia and in the Sinai desert.

In The Fate of All, an army could decide to force march for the same reasons, and with the same effects: A mere couple of days less spent crossing the desert could be vital when you are carrying only five days of supply, and make the difference between arriving at destination with an army, or with a bunch of survivors.

Is the Mission Impossible?

Probably most of us, me included, have experienced games where supply can be somewhat of a problem, but in the end almost everything can be achieved for a price.

A couple of months leading the armies of Alexander or Darius will be enough to discover that the price in The Fate of All could be really high.

So, how did Alexander succeed?

First of all, make a plan. Crossing an average fertile region with a large army could be difficult even in full summer. If you are really eager for a catastrophe, try crossing central Anatolia during winter.

Second, do not stick to the idea of “one big army moving around”. Whenever possible, split the army in smaller columns and use different supply sources for each one, avoiding depleting the countryside.

Third, be creative. Send a detachment ahead a couple of months earlier, to create a supply depot in that city along the route. Load supply on ships and have them follow the army along the coast. Create a temporary supply depot by stationing a baggage train on the planned path. Prepare supply depots along the coast by using sea shipping.

In short, don’t get fixated with an idea and try to realise it at all costs: Surrender to reality, and plan accordingly.

The Fun Has Just Begun

I am sure you will agree that, after a day’s march eating stale bread and four hours’ sleep on damp ground, nothing is more corroborating than attending one of the most celebrated human social activities: The mass slaughter of a field battle.

So, let’s take a look in detail at some of the troops that will fight and possibly die a glorious death for the King.

My biggest surprise here was that there are incredibly few confirmed, undisputed facts, even for the Macedonians. In most cases, you have to choose among dozens of diverging hypotheses, each one with its own strong points.

The Phalanx

The cornerstone of the Macedonian army was of course the phalanx: Heavy infantry moving and fighting in close formation, used to hold the centre of the battle line and to pin the enemy in place.

We know for certain that its main weapon was the Sarissa, a spear with a length from 10 to 16 cubits, depending by which source you prefer, translating approximately into 5 to 8 meters. A short sword was carried as secondary weapon and, surprise, some sources also include a javelin.

The defensive equipment was most probably a light armour made of multiple layers of linen cloth glued together (Linothorax). Ancient sources and archaeological evidence also confirm the presence of a small shield made of wood with an outer surface in bronze.

The basic manoeuvre unit of the phalanx was the Syntagma, 16 ranks of 16 men each. Each Syntagma had its own signallers and bugler and could be probably commanded independently.

Higher level units were formed by combining several Syntagmas, with names and composition differing significantly depending on the period. Without entering excessive detail, the most used formation under Alexander was the 1,500 men Taxis, formed by 6 Syntagmas of 256 men each. This is the standard phalanx unit in The Fate of All.

Whatever the details, the real strength of the phalanx came from the wall of Sarissas on its front, and from the ability to fight in tight formation. According to one of the most authoritative studies, the phalanx could deploy in “march” formation with each man having 4 cubits space (2 metres), “battle” formation with 2 cubits space (1 metre), or “close” formation with 1 cubit space (0.5 metre), probably used only for static defense.

Such spacing was, on average, tighter than in the Roman legion or in the classical Greek phalanx, as attested by Polybius writing that in battle each Roman faced two Macedonians. In the Fate of All, this translates into a higher stacking limit for the phalanx, and possibly into a greater weight during melee combat.

The Hypaspists

Despite being the elite infantry of the Macedonian army, we know very little about the Hypaspists. They were likely equipped similarly to the phalanx, but their use in battle as a link between the phalanx and the cavalry suggests they had greater mobility, also confirmed by Alexander using them for special tasks requiring speed and lightness of equipment.

In The Fate of All, Hypaspists have a higher morale than regular phalanx, and are more manoeuvrable on the battlefield.

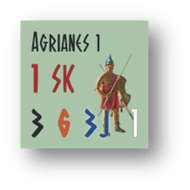

The Peltasts

The word “Peltast” identifies light infantry often deployed as skirmishers. In the classical sources the term is unfortunately used in an interchangeable manner for troops with different origin, equipment, and capabilities. In the end, it becomes impossible to distinguish one from another, and almost every modern historian has his own take about them.

According to the most accepted theory, the Peltasts were organised in 500 men units equipped with light or no armour, a crescent-shaped shield (Pelte), two or more javelins, and a short sword. Some historians propose a short spear in place of javelins, making them a sort of “light phalanx”.

Alexander’s army had three different types of Peltasts: The Agrianes, from a tribe in the regions North of Macedonia; The Thracian, obviously from Thrace; The mercenaries, from Greece or Balcanic regions not under Macedon control.

Alexander had great consideration for the Agrianes, and often detached them to independent operations or particularly dangerous assignments. Consequently, we have assigned them higher combat and morale values.

The Hetairoi, and Some Cataphract too

The phalanx always draws most of the attention, but the battles fought by Alexander were almost invariably decided by his heavy cavalry: the Hetairoi or Royal Companions.

The phalanx always draws most of the attention, but the battles fought by Alexander were almost invariably decided by his heavy cavalry: the Hetairoi or Royal Companions.

Each squadron of 200 horsemen was probably equipped with spears of up to 4 meters length, curved swords (Kopis), helmet of Boeotian type, and the same linen cloth armour used by the phalanx. The Agema squadron, 400 horsemen strong, was personally led by Alexander, and also acted as his bodyguard in battle.

You probably noticed that nothing in the equipment of the Hetairoi immediately qualify them as “heavy” cavalry. Their designation doesn’t come from the equipment or armour, but from their battlefield tactics.

Differently from most cavalry of the period, whose main goal was to attack the enemy on the flank or rear, the Heitairoi were also trained to charge frontally in a compact, wedge-shaped formation. This kind of tactics would have been suicidal against a phalanx but was extremely effective against troops of lower quality.

The Persian cataphracts possibly employed similar tactics, even though there is no clear account of a frontal charge until the Diadochi wars, after the Macedonian doctrine had become dominant. Also, cataphracts were often equipped with a bow, indicating their preference for the traditional hit-and-run tactics. In the end, we decided that, no matter the armour, only  some of the Persian cavalry could really qualify as heavy and be able to charge in battle.

some of the Persian cavalry could really qualify as heavy and be able to charge in battle.

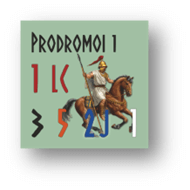

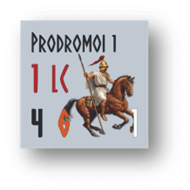

The Prodromoi

The term Prodromoi is generically used by ancient sources to identify light cavalry, with no particular attention to the differences or the exact equipment.

The Prodromoi were probably organised in 300 horsemen squadrons, equipped with sword, some kind of helmet, sometime a light armour. Depending on their origin, the main weapon could have been several javelins, a lance, or a short sarissa designed for cavalry use (a Macedonian speciality). Their operational tasks included reconnaissance, foraging, and raiding, while at tactical level they were used to cover the flanks, and surround and pursuit the enemy.

As happened for the Peltasts, it seems impossible even for professional historians to discern the exact differences among the various units, so we opted for the following subdivision:

-

Macedonian, Greek and Paiones Prodromoi, armed with lance or sarissa.

-

Thracian Prodromoi, armed with javelins.

Thracian Prodromoi, armed with javelins.

The Greek Cavalry

The cavalry used by the Greek city-states posed another interesting problem, as its traditional role as secondary, support troops was being reevaluated after the recent Theban and Macedonian victories.

In the end, in Alexander’s time the cavalry supplied by the Greek allies was probably evolving into a more effective, heavier fighting force. In The Fate of All, most of it is defined as medium cavalry, having greater combat values than the light cavalry but still incapable of a frontal, decisive charge.

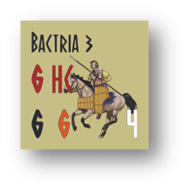

More Persians, More Glory

When it comes to the Persian army, the first problem is of course the numbers presented in the ancient historical accounts.

According to Arrian, the forces of Darius at the battle of Gaugamela amounted to 1,000,000 infantry and 40,000 cavalry. Diodorus Siculus writes of 800,000 infantry and 200,000 cavalry. Curtius Rufus tries at least to avoid being ridiculous and goes for 200,000 infantry and 45,000 cavalry.

A possible origin for these numbers is in the Greek and Roman numeral notation, both not particularly clear when big numbers must be represented. It must have been difficult for a scribe or a medieval monk, transcribing worn out papyrus and knowing nothing about the subject, to avoid errors.

These bombastic figures can be easily discarded by considering their implications on the ground. As an example, Arrian tells us that Darius at Issus had 600,000 men, including a first line of 60,000 Kardakes infantry, armed and arranged as a phalanx. Using a depth of 16 ranks and a spacing of 1 metre for each soldier, the battle line would have been 3750 metres long for the Kardakes only. Even Polybius was skeptical and tried to demonstrate that the plain of Issus simply could not contain such huge armies.

Anyway, in a rare occurrence of general consensus, modern historians agree that fielding and feeding an army above 100,000 men during the Classical Antiquity would have been extremely difficult if not impossible, except for very short periods and under very favourable circumstances. You will find that the foraging and supply limitations in The Fate of All create the same problems and give the same result.

The Kraslukianids with Boomerangs

No, there are no Kraslukianids troops with boomerangs…but it gives the idea of how little we know for certain about the organisation and equipment of the Achaemenid army.

Even today, there are lots of extremely divergent theories. The following points seem to be consistent with the available information and modern analysis, and have been used to define the details of the Persian army:

-

During the first year of Alexander’s invasion, the Achaemenid army fought in its traditional manner: light and skirmish troops, predominantly cavalry, with elite units of medium infantry and cavalry.

-

The basic Persian tactical formation was of 1,000 men, both for infantry and cavalry.

-

Javelin, bow, and sword were the predominant weapons. Armour and shield were usually light.

-

Each Persian Satrapy supplied several contingents of different troop types.

-

The heavy infantry consisted mostly of Greek mercenaries, more and more difficult to recruit after the defeats at Granicus and Issus, and the loss of the Western satrapies.

-

After the defeat at Granicus, Darius tried reforming the army to make it more effective against the Macedonians, introducing phalanx-like units, close formation training for heavy cavalry, and more.

-

When it was time for battle, there were usually a lot of Persians.

To the End of the World

The Fate of All has been a very challenging project, requiring to constantly switch between our Clausewitz and Indiana Jones hats.

The research had to face and resolve problems similar to those encountered in other developments, but on a much larger scale as there are very few authoritative, final answers to several key questions. Even after an answer was found, translating it into rules has been far from easy.

As the project advanced, the sense of wonder and admiration I always had for Alexander grew, together with a new respect for Darius and his attempts to stop an enemy far more capable than himself.

In the end, The Fate of All made me understand better why Alexander was, and still is, the Great. I hope it will be the same for you.

Very cool concepts here. Two questions. Does the ocean and coastline play any role in logistics? For example can you adopt the strategy of Memnon of Rhodes against the Macedonian supply chain? Secondly, any blog on the Persjan units forthcoming? How are for example “GreekStyle” heavy Persian infantry “Kardakes” portrayed? Thank yoy.

Ocean and Coastline: yes, as a shipping route must use only coastal sea hexes.

Memnon strategy: yep again, as a shipping route cannot be traced thru a hex inside an enemy fleet’s reaction zone.

Persian Units: I’ve actually already published some thoughts about the persian army, you may find it here:

https://trlgames.com/2023/08/13/interpreting-the-oracle-part-one/

The Kardakes are classified as medium infantry, with higher combat values than the “regular” and scarce Persian medium infantry. Despite Darius’ attempt to transform them into a Greek-style phalanx, at least from an equipment point of view, nothing attests they were particularly successful in their new role – In particular, the Heavy Infantry capability to add “weight” in combat, but you’ll have to read the rules for that 🙂

Very cool concepts here. Two questions. Does the ocean and coastline play any role in logistics? For example can you adopt the strategy of Memnon of Rhodes against the Macedonian supply chain? Secondly, any blog on the Persjan units forthcoming? How are for example “GreekStyle” heavy Persian infantry “Kardakes” portrayed? Thank you.

There is inherent risk to shipping. I would need to go back and read the rules around Supply and shipping.

Because the establishment of shipping routes requires the Alexandrian player to use his naval forces. It behoves him to ensure that potential enemy naval forces are dealt with before he starts to establish his naval supply chains.

As the Alexandrian player has to convert his navies to merchant carriers it behoves him to deal with potential naval opposition before he starts to establish naval shipping routes.

This looks likely to be the apex game on the subject. Admittedly I’ve only played Berg’s GMT game on it, but I find this campaign to be very hard to model so as the create a realistic model that serves also as an interesting game. Basically, Al was hanging it in every battle, exposing himself to campaign-ending death. If that arrow that took out good King Harold Godwinson had flown into 33X BCE instead and taken out better King Alexander we’d have a very short game. Yet it seems that the device of matching Persian losses in battles with an elevated level of Greek/Macedonian casualties unbalances the game in the opposite direction as well as being historically inaccurate. That balancing act might indeed prove to be ‘mission impossible’.

Indeed, an early death of Alexander can be a disaster for the Macedonians, but it is an undeniable historical fact that Alexander had been seriously wounded at least four times, and every time could have been the last.

In The Fate of All, the Macedonian may avoid exposing the King excessively during the battles and the sieges, but of course this has a cost as Alexander will not be able to lead the decisive cavalry charge or to inspire the besiegers with his leadership.

There’s also an optional rule called “The King Must Survive” for players not manly enough to face the decisions of the Gods 😀

The Prodromoi counter is hard to read due to the unit icon overlaping the number values, ditto for the indian elephant