When board games, especially board wargames are discussed often the topic of Chaos and Control surface. You don’t need to be a Grognard to appreciate that some games give you that God’s Eye view while other mire you in a state of flux powerful enough to cause analysis paralysis.

When we discuss chaos the word means different things to different audiences. If we creak open the pages of Merriam Webster it shows us that chaos is,

: Confusion and disorder: a state in which behavior and events are not controlled by anything

: A state of things in which chance is supreme

Similar words to chaos are:

chance-medley, confusion,

disarray, disorder, disorganization, free-for-all, havoc, jumble, mess, messiness, misorder, muddle, muss, shambles, snake pit….

The last one sounds like a doozy! Whereas control is defined in there as,

: Control – to direct the behavior, to cause (a person or thing) to do what you want

: To have power over something

: To direct the course of something

bridle, check, constrain, contain, curb, govern, hold, inhibit, keep,measure, pull in, regulate, rein (in), restrain, rule, tame

Why is the aspect and consideration of control so important to us as gamers? Why are some of the most popular wargames out today chaos driven or influenced?

Surely we as gamers want to see the perfect plan come to fruition, count the factors, measure the movement, assess the risk, and push forward my cardboard armies in perfect unison?

Or do we desire the simulated, nay, perhaps that is too strong a word, imagined chaos of battle, where plans are thwarted, troops delayed, counters attack foiled?

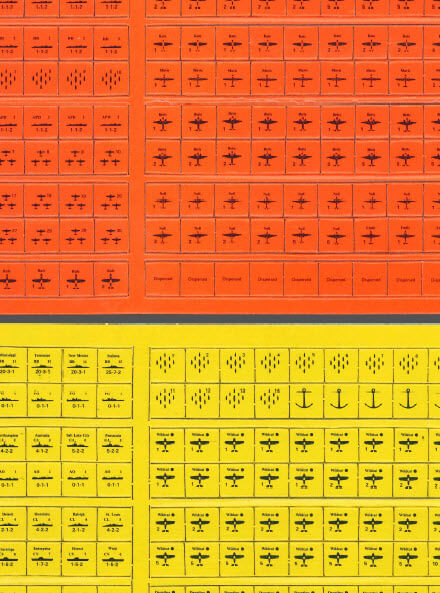

Early game designs focused more upon the factor picking, optimizing approaches to battle and achieving some semblance of war abstracted. Titles such as Stalingrad, & DDay from Avalon Hill are excellent examples, and any of the hundreds of early titles from SPI modeled more control and less chaos. Then as more games were published broader thinking evolved as designers dug into more than just accurate orders of battle and a 1d6 based CRT ranging fro 1:3 to 3:1.

We evolved.

Surely we as gamers want to see the perfect plan come to fruition, count the factors, measure the movement, assess the risk, and push forward my cardboard armies in perfect unison?

Or do we desire the simulated, nay, perhaps that is too strong a word, imagined chaos of battle, where plans are thwarted, troops delayed, counters attack foiled?

Early game designs focused more upon the factor picking, optimizing approaches to battle and achieving some semblance of war abstracted. Titles such as Stalingrad, & DDay from Avalon Hill are excellent examples, and any of the hundreds of early titles from SPI modeled more control and less chaos. Then as more games were published broader thinking evolved as designers dug into more than just accurate orders of battle and a 1d6 based CRT ranging fro 1:3 to 3:1.

We evolved.

With the concept of untried units in PanzerGruppe Guderian where you do not know your opponents strength and nor does he until you engage in combat! Chaos reigned supreme for a while there. If we fast forward to OCS from The Gamers who came along with its 2d6 result set and the surprise roll, which could move your best laid plans +/- 1d6 columns on the CRT! No control there mate! So a surprise for either player was only one combat away.

Concepts around attrition accumulating in units as they move, allowing for soft factors such as morale and political will all contributed to a lessening of control.

The break through moment for me however was the first hidden movement games I played! I was a teenager, we were both very competitive, I was unsure what I was doing, and my opponent had a propensity to cheat..’just a little bit here or there’ when we played C.V where you plotted your aircraft carrier’s movement, or Sniper! where plots were made and spotting attempts occurred to try and find the enemy. Talk about chaos. Your wits were test against your opponent every turn as you sought to achieve your objective. The level of suspense and the excitement was palpable. But these all required a opponent and ideally an honest one. Solitaire hidden movement aint much fun 😉

Another splendid approach to this is double blind gaming with a referee or with two copies of the game and a screen in between. City Fight and NATO Division Commander were my favorites in that genre.

The tension built every turn as you closed in on objectives, searched for the enemy and dashed from building to building or city to city in search sectors!

Less burdensome and more refined is of course the chit pull mechanic where no one knows who shall move first, third or last!

Chit pull of course can take many forms and for me its one of the least explored mechanics by designers. Ted Racier used a very nice method of chit pull with boundaries driven by year. Adam Stark Weathers IGS games took chit pull and allowed for certain chits to always be in the draw, others allowed for chit swaps, variable end turn markers added and special events to be included as well. The options are endless and there is more to be explored here by designers!

You will note that I left out Combat Commander and the seemingly random nature of the cards. Well the truth is it does induce some level of chaos in that you cannot always do what you want when you want, but experienced plays know that if you dump enough hands you will get the card you need or the number you want eventually. CC ends up not being that chaotic after all if you care to count cards.

I think we all cherish a little chaos, some more than others.

What about you? Are you a chaos enabler or a control master?

Don’t you mean KAOS vs. Control? Missed it by *that* much!!! 🙂

On the more serious side:

If you want to explore more of what can be done with the chit pull mechanism, take a look at Richard Berg’s Great Battles of the American Civil War (GBACW) series for GMT Games. This system uses chits to represent division-sized entities, but combines it with variable efficiency (also determined by a separate chit draw!) that determines how many activations each division gets per turn. These are hidden from the opponent, and placed in the same draw “hat” so neither side knows with any degree of certainty how often his opponent’s formations will be able to move during the course of the hour-long game turn. This creates a great fog of war (combined with a few other ingenious “out-of-my-hands” command mechanics), simulates well the “chaos” inherent in ACW combat (as well as the effect of *personality* of the brigade and division commanders), and also is the chief reason why (IMO) GBACW is far and away better than the SPI GBACW system that began with Terrible Swift Sword.

In the TSS system, the you-go-I-go turn structure meant that you had very little chance to get an opponent to cede a position without having to fight for it. In the GMT GBACW, you could use an early chit activation to move a division out *towards* a flank, creating the impression in your opponent’s mind that you intend to use later activations to complete the flanking move and put in an attack. What your opponent might not know is, that “prelude move” might be the ONLY one your division will make that hour!!! Still, if you sell it well enough, the opponent might take the “better part of valor” and pull back, not realizing his mistake until the very end of the turn!

Hmm, Ill need to try it at some point. I was unaware of the command aspect. Ive seen plenty of play, just not command phase stuff. It feels very much like GBoH with guns. That command aspect would give it a very ACW theme.

Another cracking feature, Kevin! Your enthusiasm for war gaming has no limits. 👍 The chit-pull mechanic in Rise of the Roman Republic and Carthage really add tension and chaos.

So True, a title I should have mentioned here. Thank you for reading!

This is one of your best blog posts ever, Kev.

I think one reason why early wargames were highly control-oriented was because all wargames owe their distant ancestry to the grandaddy wargame of them all: chess. The earliest Avalon Hill games had to cater to an audience with no prior experience of a wargame. Double-blind games like Midway or Jutland added chaos in the form of fog-of-war for the opponent, but you still had control over your own side.

As board wargaming developed and became a game genre in its own right, designers and thought-leaders like Jim Dunnigan shifted the reference point from chess or purely fun game mechanics to actual warfare. And so the hobby increasingly looked for ways to boost “realism” and simulation value — adding more “friction” reducing control over your own troops, and pushing the envelope in many ways over the decades, some successful and some not.

Along the way, wargames developed and retained some distinctive core concepts (grid movement, area movement, zone of control, for example) that wargamers came to learn, understand and accept from game to game, even as new concepts and systems continued to be created.

I think the pendulum swing toward “more chaos” is at or near it’s maximum now. It can’t just be packed into a game willy-nilly through lots of added “chrome.” The rise of Eurogames and an accompanying demand for lighter, faster, quicker-to-play and quicker-to-learn puts huge pressure on wargame publishing now, combined with the aging out of the original grognard population. But I think perhaps now we have the best of both worlds.

Take for example Herman Luttman, whose new “Crowbar” D-Day solitaire game you just demoed. Crowbar has tons of chaos, but the design and components are executed in a super-approachable way that even the casual gamer can enjoy. The pressure for elegance and low-overhead has also borne fruit in the games like GMT’s Skies Over The Reich — where a very “deep” wargame is said to have such great player aids, information design and programmed, lavishly illustrated rules that people can pick it up and have fun playing it within minutes.

For me, I find I like a certain amount of randomness or chaos in a wargame, but when it becomes too much I feel like it becomes determined by the chaos and it becomes another version of Candyland.

What is “too much” I agree is subjective. As an example, I absolutely hated A Victory Lost. Why? Because one can easily see that subsequent games are not very comparable because the sequence of chit activations have a HUGE effect on play. If the Axis get to pull back before the Soviets strike the resulting map will look very different than if they do not and there was no skill involved, just the order of chits selected. On the other hand, PGG I really like. The nice things is there are so many games and systems out there that no one is stuck playing a game or system they do not like.

I first became interested in chaos infused games in 1992, when I first played The Gamers’ In Their Quiet Fields I. There weren’t actually any orders rules in that game, but in reading rules for later CWB, RSS, NBS and TCS games, I really appreciated the fact that your cardboard troops can’t (or won’t) do what you want them to do. Plus, one of my regular opponents at the time was a game accountant, carefully counting out each attack so that every one was at least a 3:1. That used to drive me nuts. Lately, I’ve been playing Herm Luttmann’s Blind Swords Series quite a bit and the chaos was just perfect, and perfectly, agonizingly entertaining and simultaneously frustrating.