The following is largely quoted from Kathleen Toohey’s re write of her Masters Thesis regarding Alexander the Greats Battle tactics. Freely available on Academia.edu .

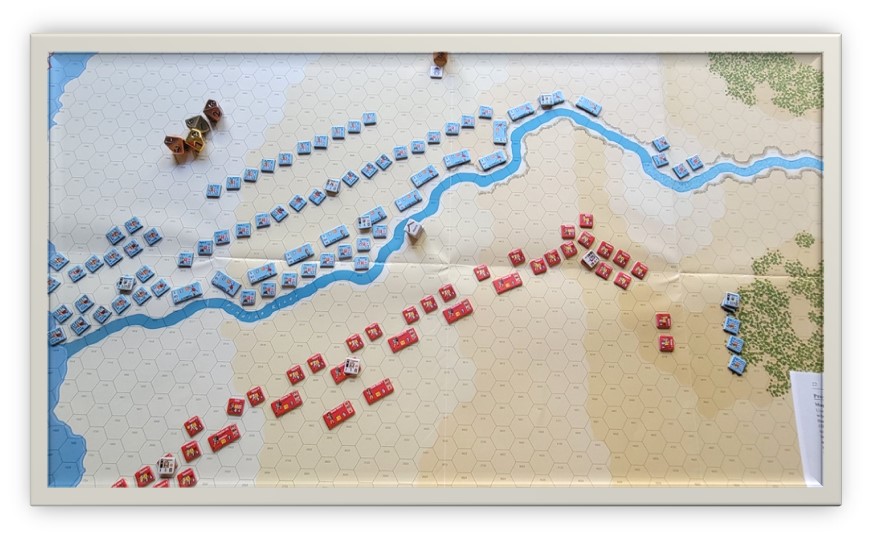

I have focused upon the chapters and sections that are relevant to the Battle of Issus and the events surrounding the battle, location and outcome. This article is a precursor for a battle AAR that will appear in due course using the Great Battles of History system – Macedonian Art of War.

One aspect that is often overlooked when we play these discrete tactical battles is why was it fought where it was and what circumstances lead to that. With several sources of referenceable data from Arrian, Cleitachus and Curtius to Diodorus we can deduct a lot. But it is often easier to allow a scholar such as Kathleen do the heavy lifting, cross referencing, fact matching, discounting of myths and all that detective work.

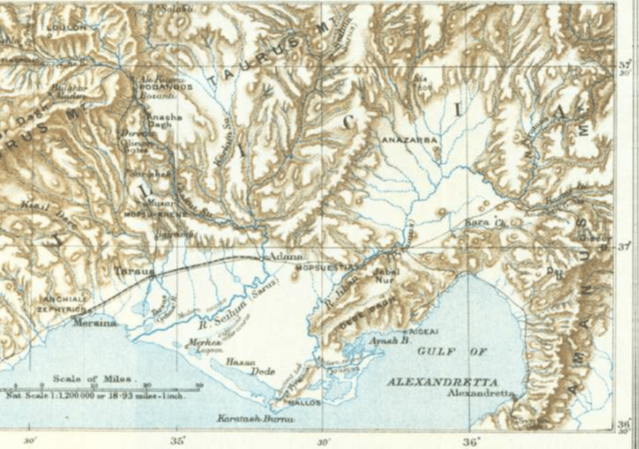

Unlike the Granicus and Gaugamela, the battle of Issus can only be understood in the context

of the events that preceded it. The battle at the Granicus had taken place in late May 334 BC.

After that, apart from some time lost besieging key cities like Miletus and Halicarnassus,

Alexander had been largely unopposed as he marched across Anatolia claiming one territory

after another for more than a year.1 During this time, three pivotal events happened.

First, in response to Alexander’s invasion, the Persian emperor, Darius III, decided to deal

with the problem himself, rather than leaving the matter to some underling. His army was

significantly larger than Alexander’s,2 and confident of success he determined to face Alexander

at a place of his choosing. To that end he assembled his army “at a place called Sochoi on the N.

Syrian plain”.3

Then after marching his army down onto the Cilician plain, Alexander became seriously ill

soon after arriving at the city of Tarsus.4 While the cause of the illness remains unclear,5 all

sources agree it was both severe and potentially life-threatening.6 This illness was a cause of

considerable anxiety and distress to Alexander’s troops; a point affirmed by both Plutarch and

Curtius.7 Alexander recovered, but he could no longer be seen as indestructible. And his

campaign in Cilicia was significantly delayed by his illness and subsequent recovery, and some

minor campaigns undertaken to secure western Cilicia.

It is at this point that the author does some extensive analysis of sources when tracing Alexander and his armies activities. It’s a great read. Alexander visits Gordium resolves the Gordian Knot problem deftly, subjugates a few townships who surrender meekly and then captures the Cilician gates, allowing entry to the plains. Arasames a local Satrap flees Cilicia without much of a fight, depending upon which source we rely on.

It is at this point that either prior to or during a swim in Tarsas Alexander falls ill for several days and finally is given a ‘cure’ by an advisor named Phillip. Alexander recovers but is not 100% by any means and spends some time tarrying and doing ‘light conquering’ to encourage the troops.

Why does any of that matter?

Both Curtius and Diodorus agree that what prompted Darius himself to lead an army against

Alexander was the news of the death of Memnon.73 The chronology of these events is unclear.74

But it can be reasonably conjectured that Darius had already begun to assemble an army in

Babylon to face Alexander, should the need arise, when he heard of Memnon’s death.75 On

hearing the news, he marched into Syria, almost certainly despatching messengers to his satraps

in his western provinces to meet with him there. And as Murison elegantly puts it, “at a place

called Sochoi on the N. Syrian plain … on a field of his own choosing, where there was plenty of

room for his cavalry to manoeuvre, he settled down to await the arrival of Alexander”.76

Only Alexander failed to come to battle.

With regard to what happened, there is again conflict in the sources, though here it remains

possible to reconstruct at least the core sequence of events, if not the precise timeline.

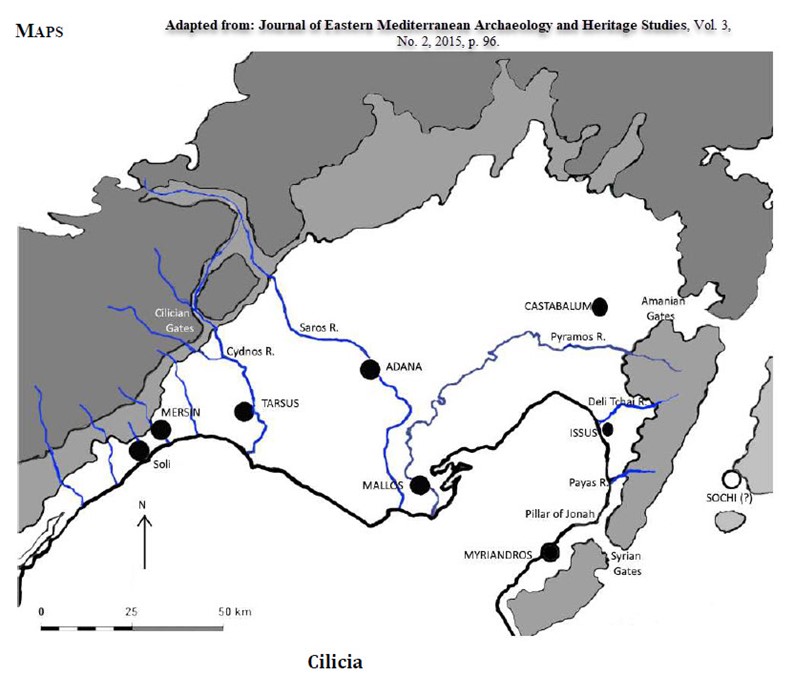

According to Arrian, after returning to Tarsus Alexander sent his cavalry under Philotas

across the Aleian plain to the river Pyramus. At the same time, “he himself went with the

infantry and the royal squadron to Megarsus” where he offered sacrifice, possibly for the second

time, to Athena.77 (Alexander’s decision to travel with the infantry, together with the sacrifice to

Athena, suggests he was still not fully recovered at this time.) From there he moved on to

Mallus. It was while he was in Mallus that he received a report that Darius “was encamped at

Sochi”, two days march from the Syrian Gates. After a quick council of war, he set off the next

day to attack the Persians, passing through the Gates on the second day, to camp near

Myriandrus.78

Taken literally, this would suggest Mallus was only four days march from Soli. But Arrian’s

account makes no allowance for two delays Alexander would have experienced on this march –

settling his invalids at Issus,79 and marching the army through the Syrian Gates.

As well, the report Alexander received on the location of the Persian army would have been at

least two to three days out of date when it reached him.

Darius, meanwhile, ignorant of Alexander’s illness,80 had grown progressively more impatient

with Alexander’s failure to appear. On Arrian’s account, Darius appears to have remained at

Sochi throughout the time Alexander was ill in Tarsus at least up until the time Alexander left

Soli.81 How long after that he waivered is unclear. Arrian gives a lengthy account, almost

certainly fiction, of the conflicting advice from Darius’ advisers on what the king should do. In

the end, he decided to march north and then west on the other side of the Amanus range to

Alexander, to descend into Cilicia through the Amanian Gates.82

In brief, despite their differences, these accounts affirm the following key facts:

That Alexander’s illness was serious enough to delay him for a significant time in Cilicia;

That this delay led Darius to abandon his original plans to await Alexander at Sochi;

That at the time the two armies were moving both Alexander and Darius were ignorant of

just where their enemy’s army was.

Murison has suggested that Darius chose to descend through the Amanian Gates in the hope

that he would be able to cut “the Macedonian army in two” by inserting his army between

Parmenio’s advance guard and the bulk of the army that had remained behind with

Alexander.86

The net of all this as far as I can tell is that Darius wisely chose the Armenian Gate so he could deploy for battle on the wide plain. This cuts off Alexander! Who then doubles back.

The Greek text Brunt translated as ‘Next’, Έκ δὲ τούτου,93 could be read as consequential rather than simply sequential as ‘next’ implies. This, I believe, is the more likely interpretation. Once he was strong enough, and it was clear he would recover, the very first thing Alexander would want do was to present himself to his troops to

reassure the army that he was alright. Both Curtius and Plutarch refer to this,94 but Arrian, seeking to play down the illness, appears to intentionally omitted any reference to it.

The next thing he would want done is to have the Gates from Syria into Cilicia secured, to

ensure his army could not be taken by surprise during his recovery. So Parmenio was sent off

with both the cavalry troops usually assigned to him, the Thracians and Thessalians, reliable light

cavalry suitable for both scouting and harassing the enemy. With him, too, went the most

expendable, of the infantry, the allied infantry and the Greek mercenaries who Alexander never

trusted for front line duties in battle.

What Parmenio did after that is much less clear. Arrian makes no further mention of him

until he is outlining Alexander’s deployment for the battle of Issus, when as at the Granicus,

Parmenio is given charge of the left wing.95

Still hanging in there?

A summation:

Sometime after the battle at the Granicus, Darius began to bring together an army at Babylon

to deal with the Macedonian invasion. At first this was probably just as a backup plan. Later,

perhaps after word reached him of further losses such as Miletus and Halicarnassus, the plan

began to evolve, and Darius made the decision not to waste his resources by having his satraps

attempt to defend their own territory. Whether this happened before or after he received news of

the death of Memnon, on whom he had first rested his hopes, is impossible to say. But soon after

that news reached him, he led his army out of Babylon to Syria. Either during that march or

possibly even before it began, orders were sent out to the satraps of the western regions to

abandon their territories, and bring the troops under their command to him. That was why

Arsames ‘fled’ Cilicia, and why Alexander encountered little resistance throughout his march to

and through that territory.

In Syria, Darius made camp for his assembled forces at a place called Sochi to await the

coming of the Macedonian invaders in a place of his choosing.

Alexander, meanwhile, after dividing his forces for the winter, had reassembled his army at

Gordium and begun his march on Cilicia. He encountered no opposition at the Cilician Gates,

and Tarsus fell to him soon after without a fight. But there, Alexander fell seriously ill and took

a long time to recover. When the worst of the illness had passed, he presented himself as

soon as possible to his troops to reassure his men that he was alright, even though he was still in

recovery.

He then sent Parmenio off to scout out their intended route to Syria and secure the Syrian

Gates and other passes. Which he did, capturing Issus along the way. Sometime after that,

Alexander began to test his own mettle by leading his army south to engage in a show of force

against Cilician resistance in the mountains behind Soli. At the end of this, reasonably satisfied

with his recovery, he returned to Tarsus and marched on Mallus, holding celebratory games and

offering sacrifices to the gods as he went.

At Mallus he learnt that Darius was at Sochi. Rendezvousing with Parmenio at Castabalum,

they then marched south to the Syrian Gates, leaving their sick and wounded at Issus on the way.

At about the same time Darius, ignorant of Alexander’s illness, decided to wait no longer.

After sending his wealth and baggage off to Damascus, he led his army away from Sochi, up

through the Amanian Gates to descend on the Cilician plains from there. What his plans were, is

impossible to say, but by the time he reached Issus he knew that Alexander had left the plains,

and all he could do was follow him. By then, word had reached Alexander that Darius was

behind him. So he turned his own army around to march back and confront Darius on a

battlefield that was not the choice of either commander.

The analysis of the marches by both sides is also very interesting, as Kathleen deduces that there are some relatively different unit placements based on the actions she has read about and we will be apply those to the above map and setup.

But we shall save that for another post.