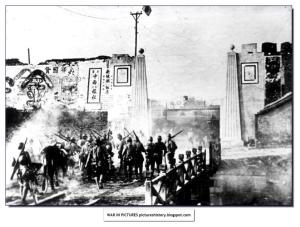

The Battle for Sihang Warehouse, where a morale boosting victory over the Japanese by Chinas forces took place is significant not because of the military value of the objective, nor the tactics used but as in many wars it was the intangible benefit that lifted an entire nation. Poorly armed remnants fought the best of the Japanese army (3rd Division) in China, their tanks, artillery and planes could not dislodge the 800 Heroes 八百壮士. Watched by the world from across the banks of the creek separating the International concessions this battle raged for days. The “800” were dedicated to fighting to the death.

Stay tuned for video play thru posted here.

The stalwart defense lifted the spirits of a nation after the fall of Shanghai. In a war that was to eventually claim over 10 million lives this battle resonates amongst many as something noble. Fought close to the International concession just across the river, Japanese officers were loathe to unload Naval Artillery fire for fear of hitting an Embassy location of another country, making the victory all the more costly.

The Warehouse::

At 10 p.m. on 26 October, the 524th Regiment, based at the Shanghai North Railway Station, received orders to withdraw to the divisional headquarters at Sihang Warehouse. 1st Battalion commander Yang Ruifu was distraught at having to abandon a position he had held for more than two months,[3] but agreed to do so after being shown Sun’s orders for the 1st Battalion to defend Sihang Warehouse.

The warehouse, also known also as the Chinese Mint Godown by those from the concessions, is a six-story concrete building situated in Zhabei District north of Suzhou Creek, at the north-western edge of New Lese Bridge (now North Tibet Road Bridge). Built jointly by four banks—hence the name Sihang (literally meaning, Four Banks)—in 1931, it sits on a 0.3-acre (1,200 m2) plot of land, with an area of 20,700 square metres (222,800 sq ft), 64 metres (210 ft) wide by 54 metres (177 ft) long, and 25 metres (82 ft) high, making it one of the tallest buildings in the area. The warehouse, used as the divisional headquarters of the 88th Division prior to this battle, was stocked with food, first aid equipment, shells and ammunition.

It started to drizzle around 3 p.m., and the fire and screen of smoke around the warehouse were gradually extinguished. The Japanese launched a major attack concentrated in the west, occupying the Bank of Communications building, and deployed cannon to the north of the warehouse. The cannon were unable to heavily damage the thick walls of the warehouse, and Japanese troops in the bank building were easily suppressed by the defenders on the roof of the warehouse, who had a higher vantage point. After two hours the Japanese gave up the attack, but managed to cut electricity and water to the warehouse.

Some time in the day, a small group of Chinese soldiers led by the 524th’s executive officer Shangguan Zhibiao and battalion field surgeon Tang Pinzi (湯聘梓) arrived and joined the battle.

Meanwhile, the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce was overjoyed at the news of Chinese defenders left in Zhabei, and news of this spread quickly through radio. Crowds gathered on the southern bank of the Suzhou River in the rain, cheering the defenders on. More than ten truckloads of aid were donated by Shanghai’s citizens. At night the trucks drove near the warehouse, and the defenders constructed a sandbag wall to the trucks, and then dragged the supplies into the warehouse. The unloading of supplies took four hours, during which three soldiers were killed by Japanese fire. The defenders received food, fruits, clothing, utensils and letters from the citizens.

The same night, the Chamber of Commerce decided to send the soldiers a flag of the Republic of China.[5][7] Regiment-sized Chinese units did not carry army or national flags during the war, so when Yang Huimin delivered the flag to the warehouse, Xie had to personally accept the flag as the highest-ranking officer present. Yang Huimin asked for the soldiers’ plans, to which the answer “Defend to the death!” was given.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nJwTWPf_xjM] Yang Huimin, moved, asked for a list of all the soldiers’ names to announce to the entire country.[5]

As doing so would inform the Japanese of their real strength, Xie did not want to release this information. However, he did not want to disappoint Yang Huimin either. Instead, he asked someone to write down around 800 names from the original roster of the 524th Regiment, and this fake name list was given to her. According to Yang Ruifu, the wounded soldiers sent out earlier that night were also ordered to say 800 if questioned about their strength. Thus the story of the “800 Heroes” spread.[3]

October 29th

The crowd gathered across the river, reportedly thirty thousand strong, was jubilant, shouting “Long live the Republic of China!” while the Japanese were furious and sent aircraft to attack the flag. Because of heavy anti-aircraft fire and fear of hitting the foreign concessions, the planes soon left without destroying the flag. Meanwhile, two days of fighting had damaged or destroyed many field fortifications around the warehouse, and the warehouse itself was also damaged.

At noon the Japanese mounted their largest offensive thus far. Attacking from all directions with cannon fire and tankettes, they pushed the 3rd Company out of their defensive line at the base of the warehouse and forced the 3rd into the warehouse itself. The west side of the warehouse originally lacked windows (as can be seen from the photos above), but the Japanese attacks conveniently opened up firing holes for the defenders. A group of Japanese soldiers tried to scale the walls to the second floor with ladders, and Xie just happened to be at the window they appeared from. He grabbed the first Japanese soldier’s rifle, choked him with the other hand, pushed him off, and finally shot another Japanese soldier on the ladder before pushing the ladder off.

A private, traumatized by the battle, jumped off the building while strapped with grenades and took out some twenty Japanese soldiers in exchange for his own life. The battle lasted until dark, with Japanese waves now frequently supported by armoured vehicles and cannon fire. Finally, after all else had failed, they used an excavator and tried to dig a tunnel towards the warehouse.

October 30th

The Japanese launched a new wave of attack at 7 a.m. on the 30th. There were fewer infantry assaults at the warehouse this time; the Japanese attack was mainly concentrated cannon fire. Because of the sturdy construction and the abundance of sandbags and materials with which to fortify and mend the warehouse, the defenders simply repaired the warehouse while the Japanese tried to destroy it. Cannon fire was so rapid, recalled Yang Ruifu, that there was approximately one shell every second. When night approached, the Japanese deployed several floodlights to illuminate the warehouse for their artillery to strike at. The battle on the 30th lasted the whole day, and the defenders destroyed and damaged several armoured cars.

The foreigners in the concessions in Shanghai did not want the site of combat to be so close to them. With that consideration in mind, and faced with pressure from the Japanese, they agreed to try to convince the Chinese to cease resisting. On the 29th the foreigners submitted a petition to the National Government to stop the fighting “for humanitarian concerns”. To Chiang, the battle was already won as most of the Chinese forces in Shanghai had successfully been redeployed to defend more favourable positions, and the defense of the warehouse now had the attention of the western world, so he gave the go-ahead for the regiment to retreat on 31 October. A meeting was arranged with the British general Telfer-Smollett through the commandant of Shanghai Auxiliary Police (上海警備), Yang Hu (楊虎),and it was decided the 524th would retreat to the foreign concessions and then rejoin the rest of the 88th Division, which had been fighting in west Shanghai. The Japanese commander Matsui Iwane also agreed and promised to let the defenders retreat, but later reneged on the deal. Xie, on the other hand, wanted to remain in the warehouse and fight to the last man. Zhang Boting finally convinced Xie to retreat.

At midnight, 1 November, Xie led 376 men in small groups toward the British concession across New Lese Bridge. Ten defenders had died, and another 27 were too heavily wounded to be moved. Consequently they agreed to stay behind to man the machine guns to cover the retreat of the remaining forces. About ten soldiers were wounded by Japanese machine gun and cannon fire during the crossing. By 2 a.m. the retreat was complete.

Aftermath:

Faced with defeat in the Battle of Shanghai and the loss of a third of the National Revolutionary Army’s best-trained troops, the failed but morale-boosting defense of Shanghai proved to the Chinese people and foreign powers alike that China was actively resisting the Japanese. The media capitalized on the defense of the warehouse and lauded the Eight Hundred Heroes, embellished from the original 414, as national heroes, and a patriotic song was also composed to encourage the people to resist Japanese aggression. However, the foreign aid that Chiang tried to canvass for did not arrive; none of the European powers delivered anything more than verbal condemnation of Japan. Only Germany and the Soviet Union provided substantial aid to China before the outbreak of war in Europe, and Germany withdrew its advisors in 1938 because of Japanese pressure.

Within the “Lost Battalion Barracks”, the Heroes languished for more than three years. The Japanese had offered to free the soldiers, but only if they disarmed and left Shanghai as refugees. Xie did not agree to these terms, and after refusing numerous offers from Wang Jingwei’s collaborationist government, Xie Jinyuan was assassinated on 24 April 1941 at 5 a.m. by Sergeant He Dingcheng and three others of his own troops, who were bought over by Wang Jingwei’s government. He died at 6 a.m. More than 100,000 people turned up for his funeral, and he was posthumously made a brigadier general of the National Revolutionary Army.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese forces occupied the foreign concessions and captured the soldiers. They were shipped off to Hangzhou and Xiaolingwei to do hard labour. Part of the group sent to Xiaolingwei escaped, and some rejoined the Chinese forces. Thirty-six officers and soldiers were sent to Papua New Guinea to do hard labour, and in 1945 when the war went against Japan, they overpowered their captors and took them prisoners instead.

At the end of the war, some one hundred survivors of the battalion returned to Shanghai and Sihang Warehouse. When the Chinese Civil War broke out, most of them wanted to fight no more and returned to civilian occupations. Later, some of them, including Girl Guide Yang Huimin, retreated to Taiwan with the Kuomintang government, while some of those who remained were persecuted in the Cultural Revolution because they were Kuomintang soldiers.