First AAR post HERE

Primary Unit participation: 1st Provisional Brigade, 5th Regiment 1/5 2/5 Bn.

Historically

We pick up the story where Commander Newton is advised of the urgency of the mission, after an already gruelling handful of days for his men in 114 degree heat.

https://permanent.access.gpo.gov/gpo88871/FireBrigadeUSMarinesinthePusanPerimeter_PCN19000315000.pdf

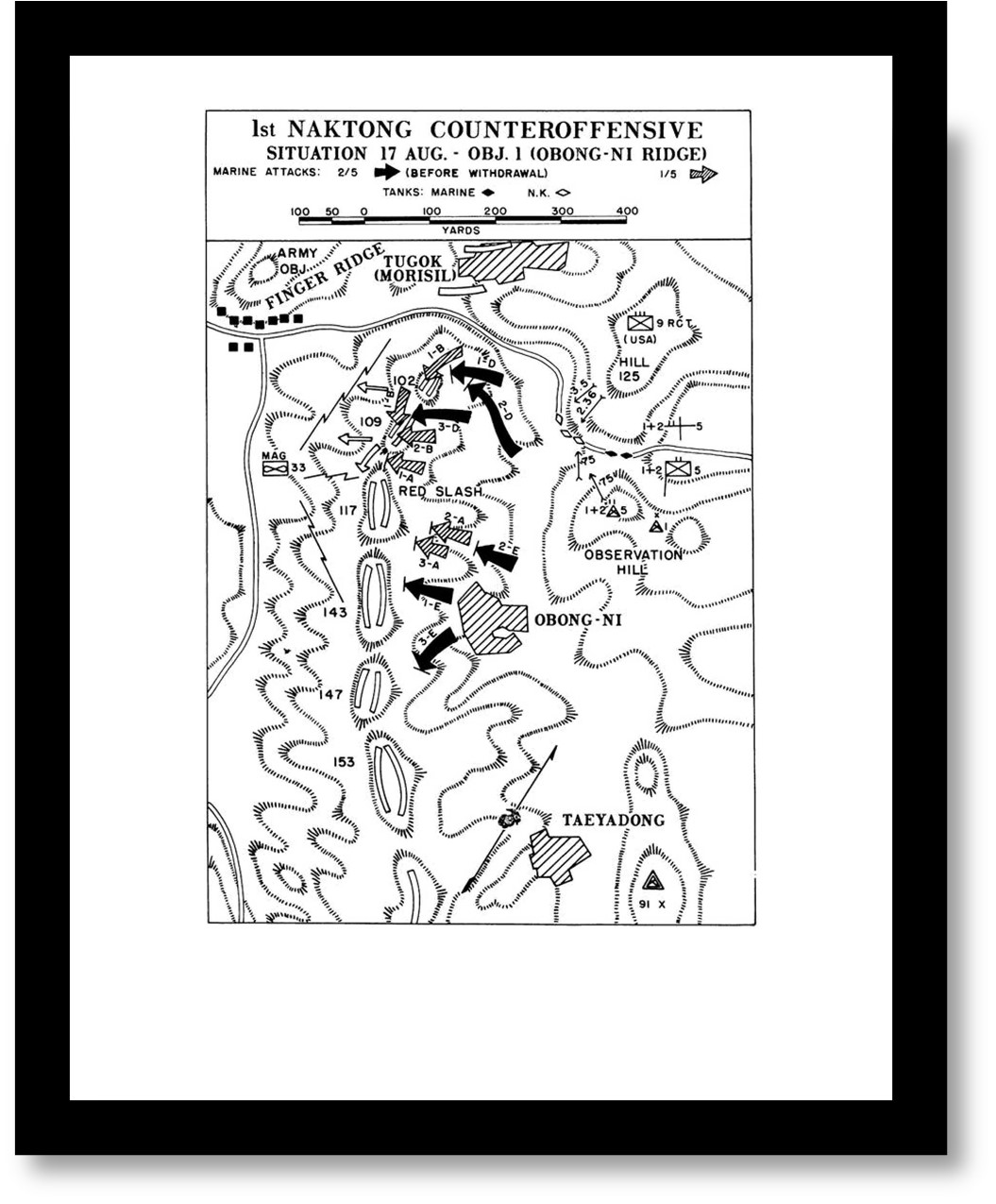

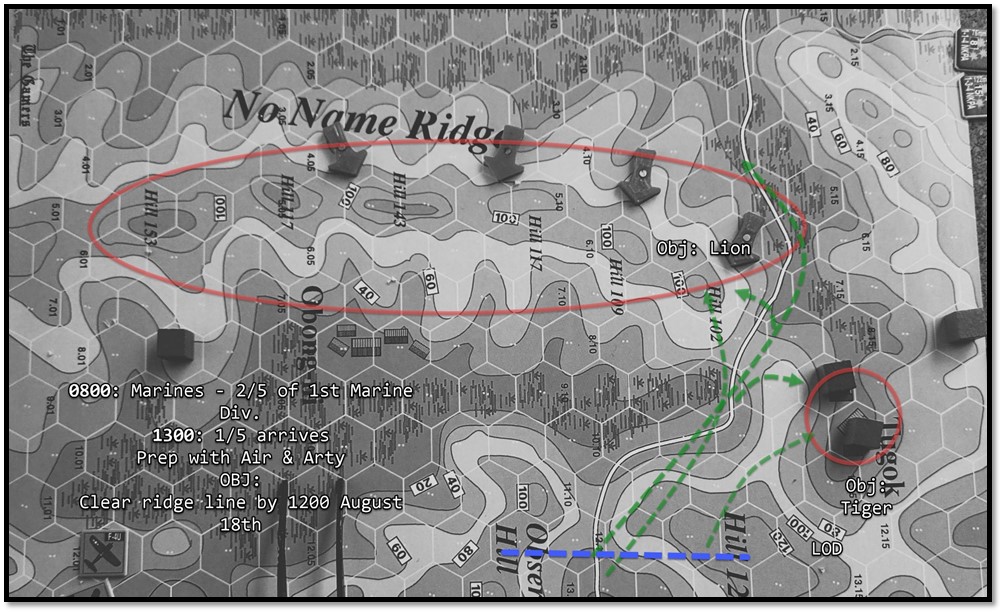

That night, the tone of the attack was set when Murray told Newton: “You must take that ground tomorrow! You have to get on that ridge and take it! Understood?” Newton replied: “Understood! Understood! This battalion goes only oneway—straight ahead!” The brigade was to jump off at0800 on 17 August as part of a planned full-scale effort by the Army’s 24th Division, reinforced by the 9th Infantry Regiment. There was a happy history of linkage between the Marines and the9th Infantry. They had served together in the battle for Tientsin during the Boxer Rebellion in China at the turn of the century, and again in the 2d Infantry Division in France during World War I. Now the 9th would operate on the brigade’s right, with the Marines as the left wing of the attack. Three objective lines were assigned to the brigade, with the first being Obong-ni Ridge. Craig and Murray made an on-the-spot reconnaissance of the terrain which was a jumbled mass of hills and gullies. Because of the type of terrain to the left and the presence of the Army’s 9th Regiment to the right, the only, reluctant choice was a frontal attack.

The shift to the new crisis area was a pressure-laden one for the Marines. Stewart, Craig’s operations officer (G-3), remembered in later years that he was advised that the Naktong River line had been broken through, threatening the Pusan-Taegu MSR, and the brigade had to move there immediately to restore the front.

He recalled:

Things were so hectic that Roise, who was commanding the 2d Battalion, which was going on the line below Masan in a defensive position, received minimum orders to move. In fact, our radio contact was out and I wrote on a little piece of brown paper, “These are your trucks, move to Naktong at once.”

Those were the only orders Roise ever got to move to the Naktong front. But they were all he needed in the hectic situation in which the Marines found themselves, for, when only a portion of the promised trucks showed up, many men in the battalion had to march until 0130 the next morning to reach the jump-off point for their attack a few hours later.

Waiting for the Marines, well dug-in and confident of victory, were the 18th Regiment and a battalion of the 16th Regiment of the NKPA 4th Division. Geer quotes a speech by Colonel Chang Ky Dok, the regiment’s veteran commanding officer: Intelligence says we are to expect an attack by American Marines. To us comes the honor of being the first to defeat these Marines soldiers. We will win where others have failed. I consider our positions impregnable. We occupy the high ground and they must attack up a steep slope. Go to your men and tell them there will be no retreat.

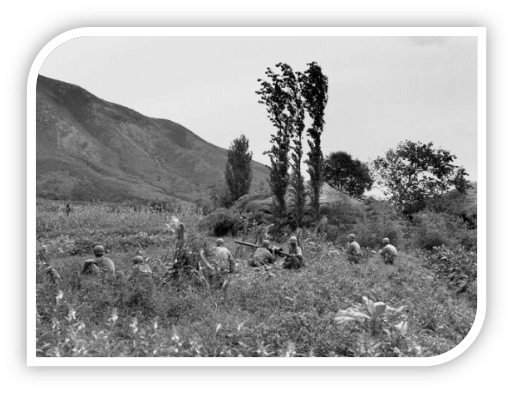

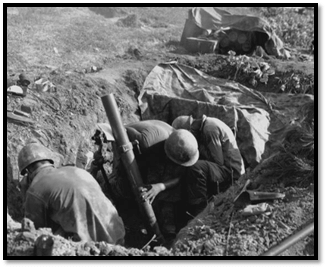

Preparation by supporting units for the Marine riflemen’s attack was inadequate. Artillery fire was ineffective. When the enemy positions were later examined, the foxholes were found to be very deep, sited along the length of the ridge slightly on the reverse slope. Thus shell fire on the forward slopes caused few casualties, nor could artillery get a trajectory to reach the enemy on the reverse slopes. Adding to the problem, there was only one air strike, Moreover, there would be little or no natural coverfor the men who had to climbtoward the six hills of Obong-ni, called by the news correspondents “No Name Ridge.”

Murray had an agreement with the Army’s 9th Infantry on the right flank that the Marines would attack first, supported by fire from the 9th. He picked Roise’s 2d Battalion to lead off. It was a very thin frontline for such a crucial moment: four understrength platoons totaling only 130 men from Companies D and E to lead the assault (with two platoons as reserves). “RedSlash Hill” was to be their dividing line. One platoon of Company E, led by Second Lieutenant Nickolas D. Arkadis, hit the village of Obong-niat the foot of two of the company objectives: Hills 143 and 147.

Driving ahead through heavy fire, the platoon fought its way to the slopes beyond. Arkadis’ leadership was later recognized by the award of a Silver Star. Now both companies were out in the open, sometimes forced to crawl upwards, met with a continuous hail of enemy machine gun and mortar fire with barrages of grenades. Casualties mounted rapidly. Joseph C. Goulden tells of a correspondent who was watching and described the bloody scene:

“Hell burst around the Leathernecks as they moved up the barren face of the ridge. Everywhere along the assault line, men dropped. To continue looked impossible. But, all glory forever to the bravest men I ever saw, the line did not break. The casualties were unthinkable, but the assault force never turned back. It moved, fell down, got up and moved again.”

One platoon of Company D, with only 15 men remaining, did claw its way to the top of Hill 109 on Obong-ni Ridge, but it was too weak and too isolated when reinforcements simply could not reach it, so it had to pull back off the crest.

Second Lieutenant Michael J. Shinka, the platoon leader, later gave the details of that perilous struggle: Running short of ammo and taking casualties, with the shallow enemy slit trenches for cover, I decided to fall back until some of the fire on my left flank could be silenced. I gave the word to withdraw and take all wounded and weapons. About three-quarters of the way down, I had the men set up where cover was available. I had six men who were able to fight. I decided to go forward to find out if we had left any of our wounded. As I crawled along our former position (on the crest of Hill 109), I came across a wounded Marine between two dead. As I grabbed him under the arms and pulled him from the foxhole, a bullet shattered my chin. Blood ran into my throat and I couldn’t breathe. Shinka, after being hit again, did manage to survive, and was later awarded a Bronze Star Medal.

Another Company D Marine, Staff Sergeant T. Albert Crowson, singlehandedly silenced two deadly machine gun emplacements and was awarded the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross by order of General MacArthur. By now, it had become clear that many of the casualties were caused by heavy enemy fire coming from the zone in front of the Army’s 9th Regiment to hit the flank and rear of the Marines, and there had been no supporting fire from the 9th. Other problems arose when some men of Company E were nearing the crest which was their objective and they were hit by white phosphorus shells from “friendly” artillery fire. Then, later, some Marines were hit in a strafing attack by their own Corsairs. By mid-day the men of the 2d Battalion, halfway up the hills, could do no more, having suffered 142 casualties, 60 percent of their original 240 riflemen.

Murray ordered it to pull back, undoubtedly lamenting the fact that he did not have a third rifle company in the battalion, for it might well have seized the top of the ridge and held it. Craig stressed this point in a later interview, noting that “without a third company, or manoeuvre element, the battalion commanders were at a tactical disadvantage in every engagement. They lacked flexibility in the attack. On defense they had to scrape up whatever they could in order to have a reserve.

” Pinpointing an example, Craigre called: This condition became critical in the First Battle of the Naktong. 2d Battalion, 5th Marines’ assault companies took heavy losses in the initial attack against Obong-ni Ridge, the strongpoint of the enemy’s bridgehead over the Naktong. Since Roise had nothing left to use, the attack stalled. Murray then had to commit 1/5 [the 1st Battalion] prematurely to continue the attack. This took time, giving the enemy a breather right at the height of the battle. That night, when the enemy hit our positions on the ridge with a heavy counterattack, Newton certainly could have used another company on line or in reserve. We were spread pretty thin, and it was nip and tuck on that ridge for several more hours. The original battle plan had called for an attack in a column of battalions, with each battalion taking successively one of the series of three ridge lines (objectives 1, 2, and 3) that shielded the NKIA river crossing It was now painfully obvious that a sharp change must be made. Accordingly, Newton’s 1st Battalion relieved the battered 2d on the hillsides at 1600 (17 August), with Company A replacing E, and B replacing D.

While the 18th Regiment had hit the 2d Battalion hard, the bravery, skill, and determination of those Marines had caused serious losses in the enemy’s ranks: 600 casualties and severe reductions in serviceable weapons. With his ammunition running low and no medical supplies so that most of his wounded men were dying, the NKPA commander’s situation was critical, as described by Fehrenbach: He knew he could not withstand another day of American air and artillery pounding and a fresh Marine assault up the ridge. Because he had a captured American SCR-300 radio, tuned in on Marine frequencies, he knew that the 1st Battalion had relieved 2/5 along the front of Ohong-ni, and he knew approximately where the companies of 1/5 were located, for the Marines talked a great deal over the air.

The relief movement of the two battalions was covered by what the official Marine history described as “devastating fires” from the planes of MAG-33, the artillery of the 1stBattalion, 11th Marines, and the brigade’s tank battalion. Then Companies A and B attacked up the daunting slopes. Simultaneously, after Murray had gone to see Church to request a change in the previously agreed-upon plan, the 9th Infantry jumped off in an attack. This eliminated the previous flanking fire on the Marines. Helped by the advance bombardment, the two Marine companies were able to make slow (and costly) progress towards the crests. Company A attacked repeatedly, trying to reach the battalion’s objective on the left: the tops of Hills 117 and 143. It proved impossible

in spite of very aggressive leadership by the officers (and gunnery sergeants who replaced them as they fell). The company could get only part way up the slopes when it was “pinned down by a solid sheet of Communist fire casualties, bled Ethel skirmish line white and finally brought it to a stop.”

Herbert R. Luster, a private first class in Company A, remembered his own searing experience in this brutal battle: It was evident no one saw the enemy but me . . . . I pulled back the bolt to cock the action of the BAR, pushed off the safety, settled back on my right foot, and opened fire. The flying clay and tracers told me where my rounds were going. I emptied the rifle. So I pushed the release with my right thumb and pulled the empty magazine out, stuck it in my jacket pocket, loaded and raised my BAR to my shoulder. Before I got it all the way up, red dirt kicked up in my face. A big jerk at my right arm told me I was hit. I looked down and saw blood squirting onto my broken BAR stock.

As always, there were gory episodes. Second Lieutenant Francis W. Muetzel in Company A was in an abandoned machine gun emplacement with his company executive officer and a rifleman from the 3d Platoon. He later recalled: The use of the abandoned machine gun emplacement proved to be a mistake. Enemy mortars and artillery had already registered on it . . Without registration of any kind, four rounds of enemy 42 82mm mortar fire landed around it. The blast lifted me off the ground, my helmet flew off. A human body to my left disintegrated. Being rather shook up and unable to hear, I crawled back to the CP. . About the time my hearing and stability returned . . . I thought of the 3d Platoon rifleman . . . . I returned to look for him. One of the mortar rounds must have landed in the small of his back. Only a pelvis and legs were left. The stretcher-bearers gathered up the remains with a shovel. On the other side of “Red Slash Hill” that was the dividing line, Company B made some progress until it was pinned down by heavy fire from a nearby village on its flank.

Captain John L. Tobin was wounded, so Fenton took over as company commander. Calling in an 81mm mortar barrage from the battalion’s weapons company, the riflemen were then able to lunge forward and seize the crests of Hills 102 and 109 by late afternoon (17 August). The two battered companies settled down where they were and tied into each other to dig in night defensive positions. With the flood of casualties, the resulting manpower shortage caused the far left flank to dangle dangerously in the air. Newton threw together an improvised unit of men from his headquarters and service company personnel to cover that flank. The mortars and artillery were registered on probable enemy approach routes, including the crossing point on the Naktong River. Then their harassing fire missions went on all night to try to disrupt the enemy.