A Review by : Eleazar Lawson

/pic3809688.jpg)

About ten years ago, I read a book entitled “SOG: The Secret Wars of America’s Commandos in Vietnam,” by John L. Plaster. I found the book absolutely fascinating, as it covered a side of the war that is simply not covered in other histories. Major Plaster told stories of mixed teams of American special forces and locals (mostly Nung tribesmen) carrying out missions that ranged from the thinkable albeit harrowing, such as reconnoitering the Ho Chi Minh trail (yes, in Laos, although you didn’t hear it from me), to the unthinkable, such as planting forged documents suggesting political unreliability of high ranking North Vietnamese, smuggling in large caches of counterfeit money to cause dramatic inflation in the North, to (my favorite) Project Eldest Son, which involved planting booby trapped ammunition, supposedly of Chinese manufacture, in supply dumps on the Ho Chi Minh trail, to sow distrust among communist allies. I will say that again: small teams of men infiltrated the Ho Chi Minh trail to plant booby trapped ammunition in North Vietnamese supply dumps. I would call this frankly unbelievable, except that I believe it.

Being a gamer, while I was reading this book, I couldn’t help but try and envision a war-game that would capture the amazing nature of these adventures, and the way they impacted the war as a whole. I abandoned the project eventually, because I felt that the unconventional nature didn’t lend itself to a traditional board war game. Fortunately for gamers, designers with more vision than me have begun to examine the role of unconventional warfare units in more detail (see the special ops detachments in GMT’s Next War Series, or, and more to the point, the way Project Delta is handled in Silver Bayonet). One such effort is Mike Force, the issue game in Modern War Magazine #35.

Mike Force is a purpose designed solitaire game putting the player in charge of “Free World” special operations forces trying to prevent communist infiltration of South Vietnam. The game, designed by Joseph Miranda, has a single 24×32 inch map, 176 5/8 inch counters, and 16 pages of rules. Players must supply a six sided die. In a fashion similar to other solitaire designs from Strategy and Tactics press, many of the charts needed for play are printed on the map, which saves space in the rules, and eliminates the need for a separate page of charts.

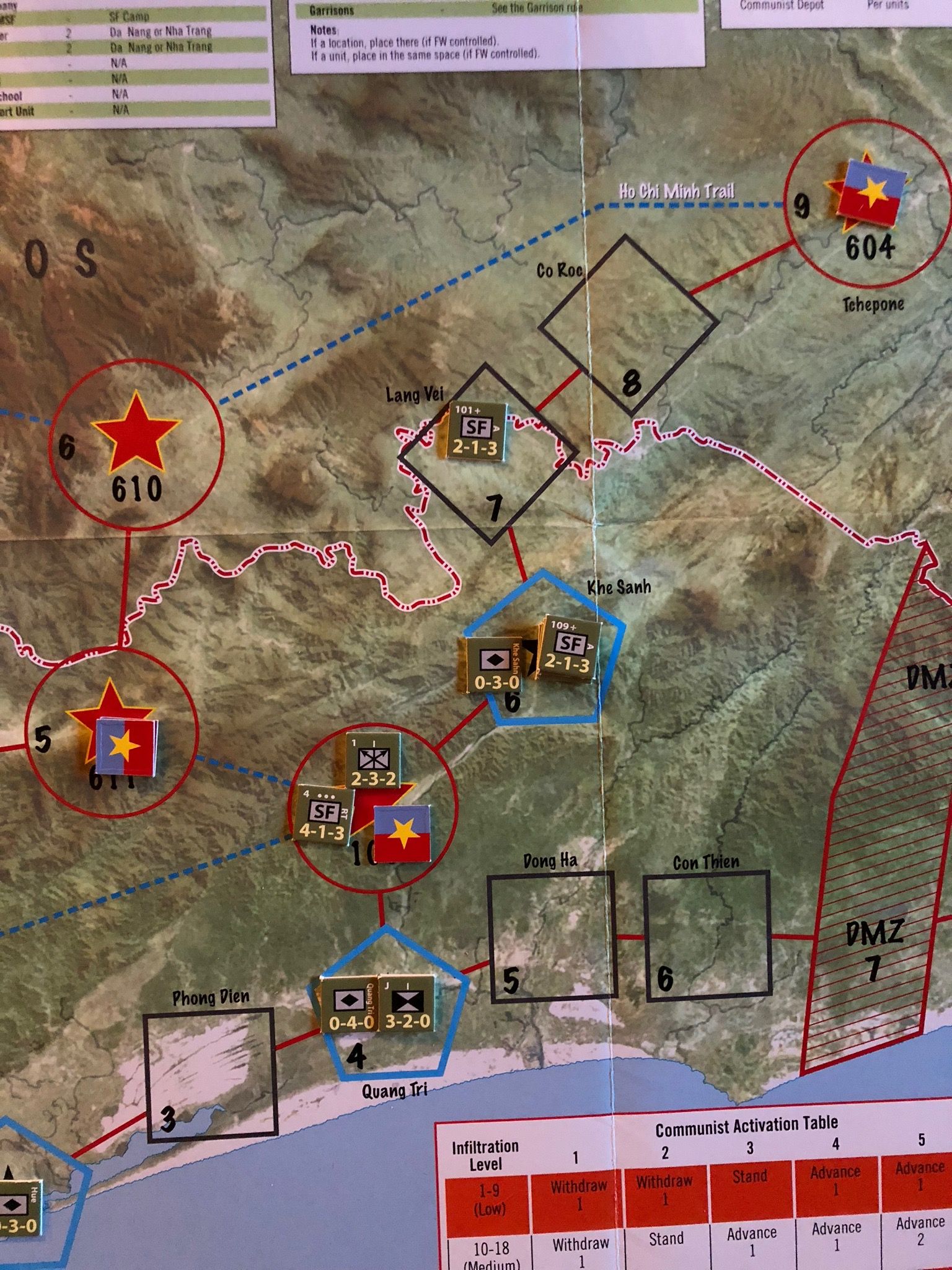

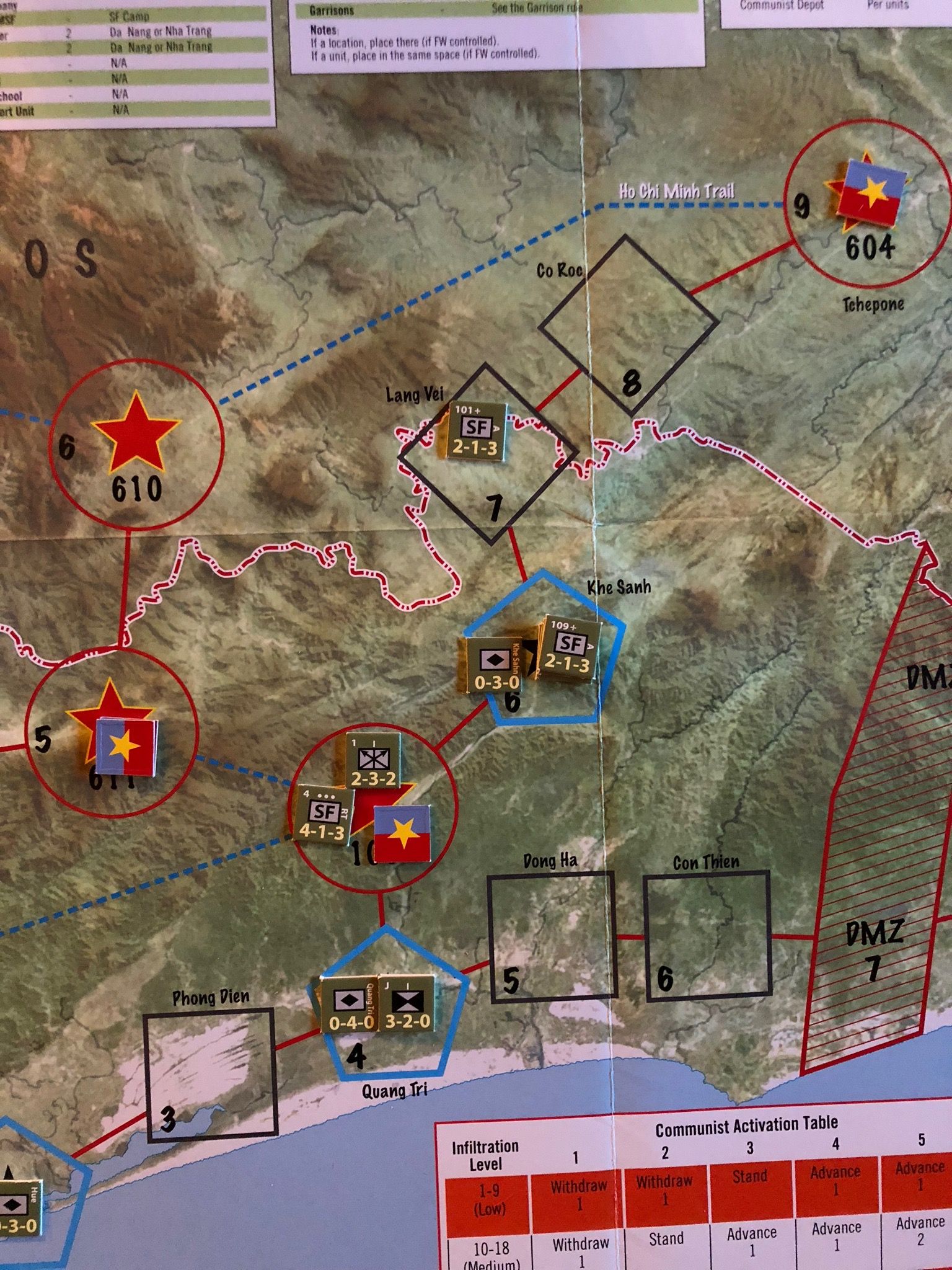

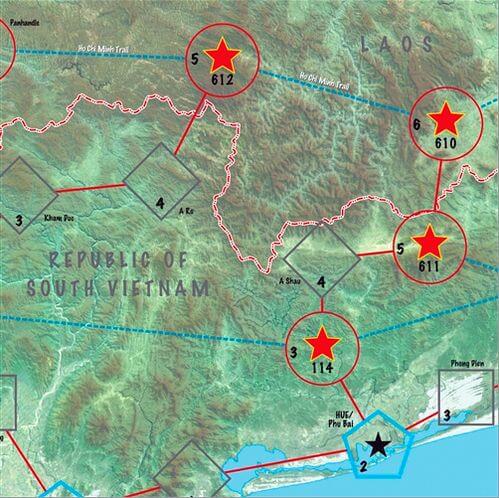

The components are clean and functional. The game uses area movement, and the map, depicting the I Corp area of South Vietnam and neighboring Laos, has roomy spaces depicting communist base areas, the DMZ, Free World bases/cities, and jungle/mountain areas. The counters are colorful, and use a mixture of icons and “modified NATO” symbols to depict infantry, recon teams, airstrikes, supply depots, etc. Free World ground units have values for recon, combat, and movement, while communist units have only a combat value.

My only quibble with the counters is the “late war” designator on some of the communist units. Some units, designated with an asterisk at the top of the counter, only appear in certain scenarios. To my aging eyes, the asterisk is almost imperceptibly small. Late-war units and the asterisk are explained in a single lonely line at the bottom of the page in the rules.

I had apparently also missed that explanation. The first inkling I had that this even existed was when I tried to set up the first scenario, and it directed me to put the late-war units aside. This caused some confusion, as I frantically re-read the rules to figure out what that meant. I eventually noticed the asterisk as well. It’s only a quibble, but the late-war units could have been marked with a bright yellow stripe or something to help us old timers out.

The rules were a pleasant surprise. The system is straightforward, and the rules are clear and well written. In my experience, magazine games, which are often excellent games when all is said and done, are plagued by production errors, poor development, and errata. I found little of that here. A few minor counter errata are noted in the rule book, and are not fatal. In addition, the fundamental game system, as I said, is straightforward, and clearly explained by only a few of the sixteen pages of rules. As befits a game about special units, much of the rules are dedicated to rules and exceptions regarding special units.

So how does the game play? Let me start by saying that I generally avoid purpose designed solitaire games, and am much more likely to play a two player game against myself than to play a solitaire game. The problem for me is that most solitaire games these days rely on almost complete randomness. Randomly draw units, place them randomly, move them randomly, then resolve random events, then roll a die, to determine randomly, if you are going to continue playing or not, because none of your decisions as a player mean anything.

I cleverly garrisoned Khe Sahn

Although there is a lot of randomness in Mike Force, there are a couple of features of the system that make player decision making meaningful, and for me, breathe life into the game.

The first is the recon/reaction phase mechanism. Free-world units use their recon values to identify hidden communist units in the recon phase. In the reaction phase which follows, airmobile units and airstrikes can move into the contested hex in anticipation of the ensuing combat phase. In this way, recon teams, inexpensive to recruit, highly mobile, and with a high recon value/low combat value, can identify targets, allowing you to bring in assets to prosecute according to your priorities.

Your priorities may depend on whether the communist units are static or mobile, how many “body count points” they are worth, and how close they are to free world targets such as special forces camps or major bases.

Which is unfortunate, since the communists are all coming through Que Son. Recon much?

The other aspect of the game that prevents it from being a mindless die rolling exercise is the replacement point/infiltration level economy. You may receive RPs or reduce the infiltration level from random events, or you may convert “body count points” for destroying communist units (and recovering special targets). RPs are used to buy new units, request MACV assets (such as airstrikes), and return units that have lost a step in combat to full strength. On the other hand, the infiltration level determines how many new communist units enter the game each turn, and how aggressively they move, so there is real value in using BCPs to lower it.

For me, much of the success of the game comes from having to balance these factors as a player. On the tactical side, you must make sure that you have assets in place to react to communist units. On the strategic side, you must decide whether to focus on building units or reducing the communist infiltration level, or to take a balanced approach.

Since victory depends on either building special forces camps or reducing the infiltration level to zero, stressing one or the other can lead to victory, but unexpected events or a miscalculation can easily unhinge your efforts, so some might argue for a more balanced strategy.

Ultimately, the challenge is not one of maneuver (your reaction forces can move pretty much anywhere) but of resource management; you have multiple fires to put out, with limited tools. I found myself sweating more than a few times, as I faced multiple communist onslaughts, with only a handful of reaction forces available. I believe that this is an intentional aspect of the design, and it is well done.

A turn 5 “Communist Big Offensive” leads to a dust-up at Que Son. As the name implies, the CBO is both big and offensive.

There are four scenarios, each depicting a different part of the war. While all of the scenarios have a lot in common, the starting conditions, in terms of units and starting infiltration level, vary dramatically. This, coupled with some additional events and communist units in the later scenarios, allow for a different feel and a different set of priorities. Each scenario is 7 game turns long, and once you get the hang of it, turns go pretty quickly. It is not unreasonable to finish a game in an hour or two depending on the scenario, making multiple playings a real possibility.

To summarize, I will briefly list the things I like and the things I don’t like. I would say pros and cons, but some of my pros may be your cons, and vice versa.

Things I like:

1) Theme: You can’t beat the topic, and I love the feeling of sending recon teams out to find the enemy. And I don’t care who you are, using your Combat Talon to recover a special forces HALO team from the DMZ, even abstractly, is cool all day.

2) Playability: The system is straightforward, and I think it works rather well. Such complexity as there is come from the multitude of special units, and the play of the game itself. That is, deciding what to do is complex, but the well written, short rules ensure that figuring out how to do it is not.

3) Decision making: As noted in #2, there are a lot of decisions to make, and unlike a lot of solitaire games, I felt like my decisions actually had some impact on the outcome of the game.

4) Short playing time: Play it out; if you mess up, set it up and play it again. You can easily get two or three plays in in a long afternoon.

5) Replayability: A lot of solitaire games seem to fall into a pattern, or are just so random that there’s no rhyme or reason. Here you have four scenarios with diverse starting conditions which each offers its own challenges. In addition, sending mike forces out to attack NVA columns is actually fun enough that I can see this game getting a fair amount of play.

Things I don’t like:

1) Randomness: I admit there’s a lot, but there’s not much chance of getting away from this in a solitaire game. I guess the beauty comes in the RP/infiltration level balance which gives you something to do other than roll dice and see if you roll well enough to win.

2) Abstraction: Sorry, but I’m an old hand, and I still appreciate a little more grit in my games. The systems here are very abstract. Combat is resolved by rolling a die and comparing to your combat value to see if you hit. Easy? Yes. Functional? Sure. Simulation value? Zero. As far as I’m concerned, it will never be as meaningful as a combat results table, where you compare the relative strengths of units, and roll dice against a range of realistic possibilities. The roll a die/compare to your hit number does allow combat to be resolved quickly which keeps the game moving, and I admit that’s a good thing.

While the randomness and abstraction will prevent Mike Force from being considered (by me at least) a serious simulation of this topic, what you have here is a well crafted board game, where real decisions prevent it from becoming a dice rolling exercise with a dash of Ho Chi Minh flavoring. I can honestly say that I enjoyed playing Mike Force. In terms of an overall numeric rating, I was pleasantly surprised enough that I must award a solid 7.

For what its worth, this review is dedicated to the memory of Roy Mayberry, dear friend and colleague, and a real life MACV/SOG. He was a member of an incredible group of American warriors who walked the Ho Chi Minh trail. Roy made it back, even though many of his brothers did not. Gentle in peace, a fury in war, and one of the finest human beings I will ever know.

Don’t become The Mouth of the Magazine Game!