Welcome to EXCLUSIVE coverage of Less Than 60 Miles, an article from the designer:

Movement and Terrain

In war, events of importance are the result of trivial causes.

Julius Caesar, “De Bello Gallico”

For a real commander, planning and organizing the movements of a mechanized unit is not a trivial task and can easily end up in a disaster when badly executed. Actually, most of the Command Staff time is dedicated to movement planning.

In most simulations, you don’t have this problem. You usually have two movement modes: Standard Mode, where your unit has its full combat potential and move decently across most terrain, and Road Mode, where your unit has reduced combat potential and moves very fast across most terrains. So, your tanks must move across a wooded area to attack a defensive position? Kids’ stuff, you just pay 4 movement points for the woods and immediately proceed to assault the enemy, in perfect combat formation.

Or maybe not. According to US Field Manual 34-130 – Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield (1994), terrain is classified into three broad types:

| Terrain Type | Unopposed Movement Speed |

| GO | 24 km/h |

| SLOW-GO | 16 km/h |

| NO-GO | 1 km/h |

Now, let’s see how US FM 34-130 classifies wooded areas:

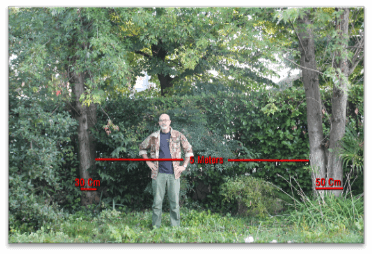

| Trunk Diameter | Tree Spacing | Terrain Type |

| Less than 5 cm | More than 6 meters | GO |

| Between 5 and 15 cm | Less than 6 meters | SLOW-GO |

| More than 15 cm | Less than 6 meters | NO-GO |

In plain terms, this means that a mechanized unit advancing in combat formation would need one hour to cross one kilometre of impassable terrain like, well, my garden.

In plain terms, this means that a mechanized unit advancing in combat formation would need one hour to cross one kilometre of impassable terrain like, well, my garden.

The bottom line is: a mechanized unit moving in combat formation is painfully slow on almost every terrain except a featureless plain. For “painfully”, I mean it could take one or two days to cover 20 km in an average wooded area.

The standard procedure for tactical marches across rough terrain is to form one or more columns, thus allowing each column to move along small roads or trails and avoid the most difficult points. When near the objective, units will move in predefined regroup areas and only after reorganizing they will be ready to attack an enemy position. During the reorganization time, the unit is vulnerable to enemy reactions unless the commander organized a defensive screen protecting the unit. Several armies developed their own unique approach to this problem (for example Warsaw Pact’s “Assault from March”), but its impact on an operational simulation cannot be overestimated.

Call In the Reconnaissance Officer

In Less Than 60 Miles, these movement problems are reproduced by the interaction between a Unit’s Posture and the Map itself.

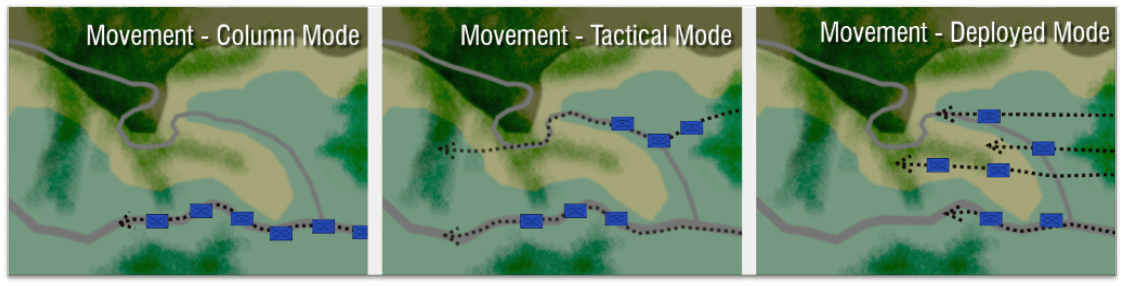

A Unit’s Posture determines its Movement Mode. Column Mode uses roads or even trails not represented on the map to their maximum advantage. Tactical Mode employs multiple columns and gives decent combat power, at the price of forcing a part of the unit to move across SLOW-GO or NO-GO terrain. Finally, Deployed mode prioritizes immediate combat power and forces the unit to move across any terrain faced.

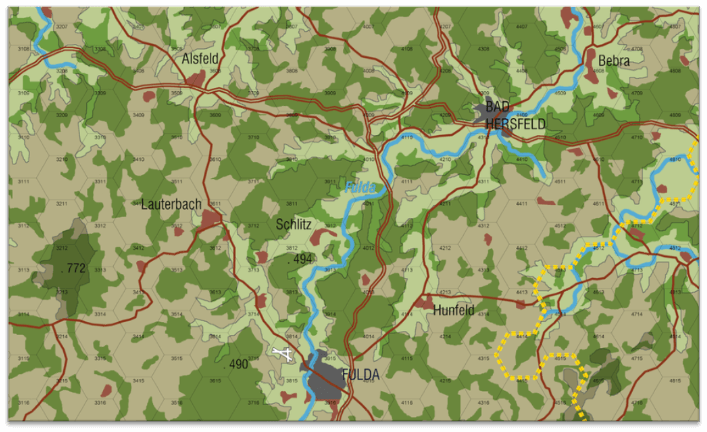

The map we decided to use is a simplified 1:500000 topographical military map, with most terrain features not “normalized” and having more than one terrain type in each hex. As the terrain actually crossed by a unit depends by its Movement Mode, the same hex could be Plain Terrain when moving in Column Mode and Forest when moving in Deployed Mode.

When Movement Modes and Map are put to work together, planning a brigade’s movement is suddenly not so obvious anymore: what’s the best route for moving from point A to point B? How long will it take for the units to reach their objective? Moreover, using main roads whenever possible becomes a top priority, as in real military planning.

As a last note, the movement rates used in Less Than 60 Miles were compared with custom scenarios in Steel Beasts Professional, a spectacular military training application, and values were adjusted accordingly. A big thanks to Ulf Krahn, our man in Stockholm, for his effort on this.

The Damned Autobahn Is Jammed

More surprises came from researching road movement. According to “FM 34-130, intelligence preparation of the battlefield” a US heavy Division moving on a road and using a single route forms a column 247 km long. Yes, that’s not a typo: two hundred forty-seven kilometres. If march is organized on three different routes, the column is “only” 130 km long. Quite different from the single counter with a “Road Mode” marker we typically see in a wargame.

This is simulated in Less Than 60 Miles by forcing players to pay movement point penalties if units moving along a road are too packed together, creating the classical traffic jam.

Seven Days to the Rhine

Crossing water obstacles is usually considered a minor hindrance for modern mechanized units: you pay your extra 3 movement points and keep moving. Yes, Rhine river could be a problem, but in 1985 anything smaller would have been crossed in a matter of minutes.

Actually, several Warsaw Pact artillery and trucks had no amphibious capabilities, and the same applies to the most used West German Armoured Fighting Vehicle, the Marder.

Actually, several Warsaw Pact artillery and trucks had no amphibious capabilities, and the same applies to the most used West German Armoured Fighting Vehicle, the Marder.

This means that your tanks are going to cross, but you’ve left everything else on the opposite river bank.

Even for units with amphibious capabilities, crossing an unbridged river is a bigger problem than expected. Tanks must be equipped with snorkels, and a not too steep river bank must be found. Non-floating vehicles can be stuck on the river bottom by mud or hidden rocks. Vehicle losses were the norm even during organized manoeuvres and were of course removed from official propaganda movies.

In Less Than 60 Miles, Players will have to choose among several options when facing a river crossing. An Amphibious Unit may opt for a Hasty Crossing using snorkels and floating equipment, risking attrition. More prudent and slower approaches are Prepared Crossing with Combat Engineers assistance, or Engineer-built Ribbon Bridges.

Combat

Ten soldiers wisely led will beat a hundred without a head.

Euripides, “Ion”

The overall combat system is inspired by NATO: Division Commander, in my opinion one of the most realistic portraits of modern mechanized warfare.

This brings to life a combat model where unit values have only a limited impact, and a lot of other considerations make the real difference. Reconnaissance, tactical deployment, support by nearby units, command control, electronic warfare, training, combat attrition and supply are only some of them.

The Attack – Defense Paradox

Combat system also changes one of the oldest cornerstones about unit values: a unit attacks with its attack value and defends with its defense value. Simple, clear. Why mess with this elegant concept?

Let’s take as example a couple of your favourite units: two US M-1 Armoured Battalions with hypothetical 7-5 values. Now, put these two identical battalions moving one against the other, in perfectly plain terrain with nothing in it, and you’ll immediately see the problem of this old paradigm:

Let’s take as example a couple of your favourite units: two US M-1 Armoured Battalions with hypothetical 7-5 values. Now, put these two identical battalions moving one against the other, in perfectly plain terrain with nothing in it, and you’ll immediately see the problem of this old paradigm:

-

When battalion A is attacking, it attacks on the +2 column (7 attack – 5 defense).

-

When battalion B is attacking, it attacks on the +2 column (7 attack – 5 defense).

Something wrong here. Why the attacker always has an advantage? What the hell is the defender doing? There’s absolutely no cover for the attacker, and unless the defending crews are drunk and waiting like sitting ducks, this fight should be at least even. Yes, the attacker may concentrate its forces better, but it’s also advancing and more exposed to enemy fire.

Something wrong here. Why the attacker always has an advantage? What the hell is the defender doing? There’s absolutely no cover for the attacker, and unless the defending crews are drunk and waiting like sitting ducks, this fight should be at least even. Yes, the attacker may concentrate its forces better, but it’s also advancing and more exposed to enemy fire.

These considerations gave birth to the “variable value” combat rule, where the defense value actually used by a unit in combat will vary depending on the tactical situation. An armoured unit will be more dangerous when attacked by other tanks, while a mechanized unit will be in trouble when attacked by tanks in a terrain offering no cover.

The Kings of Battle

There’s no need to stress the importance of artillery and air support (both fixed and rotary wing) in a combat. In Less Than 60 Miles, it is critical as it should be.

That said, we tried to avoid reducing the Kings of Battle to a simple number added to the units’ combat value. Here too, the idea is to offer Players several possible choices about how to use combat support to its best effect.

Does the tactical situation require a heavy Barrage Fire, or maybe assigning some guns to a preliminary Bombardment would be a better idea? Should you keep some battalions ready for Counter-Battery fire? Are those towed guns too slow for Shoot & Scoot and exposed to enemy Counter-Battery fire?

Moreover, the actual impact of artillery on combat cannot be predicted beforehand. The fire coordinates could be vague or wrong, the enemy could have better cover than expected. When Players will know the precise effect of their barrage fire, it will be too late to change their mind.

Even Combat Air Support cannot be simply assigned as an afterthought. CAS must be planned and coordinated between Air Force and Army to be effective, and this process could require up to several hours not counting the time needed for aircrafts refuel and loadout. A Player not investing time and precious Command Points to define and establish CAS Areas will find himself with little or no Combat Air Support.

One thought on “Less Than 60 Miles Designer’s Notes, Part 2”

Comments are closed.