Editors note see the announcement for this here: @TRLGames

Designer’s Notes by Fabrizio Vianello

Once again, we’re back to the period that was the background for most of my (and probably yours) juvenile years: the bleak, gloomy confrontation between East and West, permanently on the verge of becoming the most dangerous conflict humanity had ever seen.

The background and causes for Third World War have already been discussed in the 1985: Under an Iron Sky designer’s notes, available for downloading on our site, so I’m not going to repeat them here. Instead, I’ll try to focus on the particular aspects and problems of an aeronaval campaign in Northern Europe, both from a real and from a design point of view.

The Battleground

Of course, the first step of game development has been the map. Given the geography of the Scandinavian peninsula I was prepared for a difficult task, but it turned out much worse than that.

Practically every single fjord required a decision about how to represent it and the consequences on adjacent fjords, ports and rivers. Moreover, every single hex had to be examined from several points of views: Does it have roads? I don’t mean big or even single lane country roads, but ANY road at all? How many dozens of lakes lay in that particular 15 km area? Is that river to be considered an impassable fjord, or maybe a mechanized unit could cross it with appropriate engineer support? Moreover, as our Swedish military consultant Ulf Krahn explained me, several Scandinavian forests are studded with boulders so big that is almost impossible to cross them.

In the end, all these considerations gave birth to the various types of Arctic terrain, where “Arctic” does not necessarily stand for “cold”. Arctic could represent a terrain completely devoid of roads and tracks, or having more lakes than you ever dreamed of. The final result is in my opinion the most detailed map of Scandinavia ever included in an operational simulation.

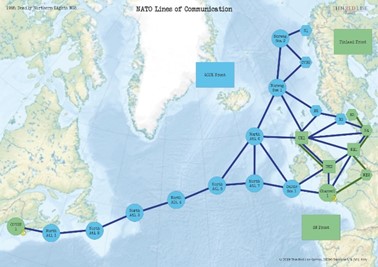

Despite that, the map alone wasn’t enough. Off-map bases, going as far as Leningrad and Northern Scotland, have been included, and the Lines Of Communication maps covers an additional area going from US East Coast to Moscow.

As a final touch, control of strategically important areas outside the map boundaries can have a decisive effect on the whole campaign: GIUK Gap, Finnish Front and Schleswig Holstein peninsula will have a direct effect on victory or defeat, and it will be up to each Commander to decide if that precious fighter squadron is needed at Tromsø or must be committed to Iceland defense.

The Sky is the Limit

Even more than in Central Europe, air power is the cornerstone over which a Scandinavian campaign will fail or succeed. Ground troops may occupy or control objectives, ships may transport men and supplies, but in the end only the control of the skies will ensure the survival of the ground and naval elements of the triad.

The basic elements of 1985: Under an Iron Sky Air Warfare have been maintained, but the sheer size of the operational front required the introduction some additional considerations on combat radius and number of squadrons each airfield can support.

Let’s see the combat radius problem: A Soviet squadron taking off from Murmansk to strike Bodø has an 800 km trip ahead – more or less the distance from Warsaw to Frankfurt, not counting that Finland and Sweden are right in the middle. A similar incursion against Trondheim would require a 2400 km round trip, once again flying directly over Finnish and Swedish air space.

NATO has similar headaches, as taking off from Scotland or Northern Germany to support ground or naval operations around Bodø requires a 2800 km round trip, but the problem is mitigated by the Co-located Operating Bases program, giving NATO several fully equipped airfields in Norway.

Therefore, deciding where to base aircraft squadrons and plan their use becomes essential, even considering that most airfields only have a limited support and repair capacity – you cannot simply place everything at Murmansk and hope for the best. On the Soviet side, the problem is worsened by the absence of in-flight refuelling systems on many aircraft and by a chronical shortage of air tankers, as reflected by shorter Combat Radius and worse Interception Modifiers.

Another important aspect added to air warfare is of course the interaction with naval forces. Carrier Battlegroups have been added, as the possibility of missile Stand-Off air strikes against ships. Air forces also play an important role in helping or denying detection of naval forces.

Boots on the Ground

An important problem both sides must face is how to move troops to their objectives. Due to the distances involved and the scarcity of roads, simply moving by land is not going to work in most cases, so one of the following approaches must be taken:

· Airdrop missions using heavy transport aircrafts and airborne troops.

· Air transport missions bringing airmobile troops to a friendly-controlled airfield

· Helicopters moving airmobile troops from a friendly base or ship to a plausible landing zone

· Amphibious landing ships transporting marines ashore

· Naval transport to a friendly-controlled port. This is particularly important for Warsaw Pact, as most of its land power relies on heavy mechanized formations that must be sealifted to a functioning port.

When the troops are finally ashore, every effort must be taken to support and protect them, as once they’re gone there’s usually no replacement, particularly for NATO. A single brigade can be expendable in Central Europe, but in the Arctic it’s all you’ll ever get.

Oil, Ammo and Canned Food

Whatever the mean used for bringing the troops in, the problems are not over. Troops need supply, and they will probably need it fast and in considerable quantities. In most cases there will be no direct connection to the overland supply network, so supply must be transported on site. Several methods are possible, each one with its own advantages and drawbacks:

· Air Resupply missions by heavy air transports: This will work fine if an operational airfield is available but just airdropping supply in the countryside will probably ensure only a bare minimum for survival.

· Transport by helicopters: No airfield needed, but even the biggest helicopters have not enough lift capacity to keep a brigade supplied during high intensity combat.

· Debark by Landing Ships: Cargo in a Task Force can be loaded on Landing Ships and subsequently unloaded on a suitable land strip, but the process is slow and sometime dangerous.

· Unloading at port by ship: if you have the luxury of an operational port, this is of course the best method.

In short, you’ll need troops to control an airfield or port to use as supply base, but you’ll need supply in order to have troops able to fight for it, and you’ll need aircraft within strike distance to protect the air transports and ships needed to bring in the supplies. Last but not least, the Soviets are going to need additional supply for repairing captured airfields and ports. NATO is probably better equipped for solving this conundrum, but both sides will find it challenging.

As a final note, never forget that your hardly stockpiled supply can be bombed by enemy air strikes or destroyed by special forces incursions.

The Naval War

The naval system is fully integrated with its ground and air counterparts. Some of its elements (for example the Task Force Tactical Display) have been inspired by Task Force, a very interesting SPI simulation deserving in my opinion more recognition. The rules have been refined and tested running custom “Command” scenarios, a computer simulation already used during the 1985: Under an Iron Sky development, and the combat outcomes adjusted accordingly.

The final result is that naval forces cannot survive for long without effective air support – Moving a Task Force inside an enemy Air Superiority Area could be the last bad idea you’re going to have. At a minimum, an effective and well-based Interception force must be available to stop enemy air strikes, and adequate support by submarines or fast attack boats must be ensured.

Amphibious Landings have been an interesting problem, as the opposing sides adopted different solutions.

The Soviet Navy, probably due to budget constraints, maintained a traditional approach of having troops and supply embarked and debarked directly by landing ships. A notable exception was the use of hovercrafts, but apart being spectacular they didn’t add much to the old Second world war style solution.

United States and UK developed a more flexible approach, certainly requiring more money and a more seaborne mentality. US Iwo Jima and Tarawa classes, and to a lesser extent UK Fearless and Round Table classes, may use Landing Craft Units to bring troops and supply ashore, or debark them by using their embedded rotary-wings assets. This gives NATO a decisive advantage when it comes to amphibious operations.

Whatever the chosen method, the time needed for debarking troops and supply must be considered and contingency plans must be made should bad weather prevent or hamper air cover.

The Northern Armies

Sweden

Despite an apparently strict adherence to the neutrality concept of “Nordic Balance”, Sweden had been often labelled as a “Secret NATO Member”. In 1985 a line of communication was active between Swedish High Command and NATO’s AFNORTH, and plans for an active intervention by special forces and aircraft in case of a Soviet attack against Finland would have been executed with little or no hesitation.

Moreover, Swedish armed forces would have been a serious problem for any less than determined Soviet offensive.

The Army could count on more than 20 peacetime regiments, forming the backbone of 27 wartime brigades with artillery and special forces support. Several dozens of Home Guard battalions would have provided local defense and garrisons.

Swedish Air Force was probably among the best in Europe, counting 24 fighter-bomber squadrons equipped with the excellent JA37 / AJ37 Viggen and some older but still functional J35 Drakken. Also, the Bas 60 / Bas 90 war plan would have allowed Swedish squadrons to disperse among dozens of small, camouflaged airfields, making practically impossible for Soviet Union to neutralize Swedish Air Force by bombing its bases.

Swedish Navy was small, but its strong submarine contingent and extended coastal battery network could have been able to inflict some serious losses to any enemy amphibious landing attempt.

Finland

The small but combative Finnish Army would have been mostly busy defending the Southern part of the country, not represented on map, and would have used ambush and guerrilla tactics in the Northern areas. Considering the almost complete absence of roads and infrastructures and the swampy terrain covering most of Northern Finland, any Soviet advance would have been slow and probably costly as reflected by the Finnish Front rules. Despite these problems and the more than probable Swedish reaction, violation of Finnish neutrality is a proposition difficult to avoid for Warsaw Pact, as Finland’s air space sits exactly in the middle of any attack route to targets in Norway and Sweden.

NATO Forces

With the increasing Soviet commitment in North and Baltic Seas during the seventies, Norway strategic significance in NATO planning increased accordingly. In 1985, several steps had already been taken to ensure NATO’s capability of reinforcing Norway and Denmark in case of war, and more were under preparation.

Denmark

The small Danish army chronically suffered from manpower shortage, poor training and low ammunition reserves. To make things worse, the reserve system had a low readiness level and the national will to fight a bloody, prolonged battle was at best questionable.

Air Force had good equipment, particularly the three F-16 squadrons, but small numbers and insufficient flight hours mined its capability to successfully oppose a serious Warsaw Pact’s offensive.

Danish Navy had some good assets, such as Missile Frigates and Fast Patrol Boats, and could have contributed in a significant manner to the defense of Skagerrak and Kattegat Straits.

Norway

With a population of 4.5 million, an extension of 385,000 square km (more than Germany) and 25,000 km of coasts, Norway is definitely a peculiar country. Its historical neutral stance still had consequences in 1985, as despite recognizing the desperate need for reinforcements in case of war, no foreign troops were allowed to station in Norway. Even combined NATO exercises required special authorizations in order to be conducted.

Norwegian ground forces were of course small, but they could count on an efficient mobilization system to quickly raise up to 12 additional brigades plus several Home Guard battalions. The main weakness was the lack of air defense assets, a problem under scrutiny in 1985 but that unfortunately would have been fixed only a few years later with the acquisition of US I-Hawk weapon systems.

Norwegian Air Forces had good equipment and training, but with only five fighter squadrons they would have been desperately outnumbered in the initial stages of a serious Warsaw Pact offensive.

Navy’s best assets were probably the Kobben-class diesel submarines, based on the German Type 205 design, and the Storm-class Fast Patrol Boats armed with Penguin anti-ship missiles. Also, a formidable array of Coastal Batteries was strategically placed for defending main ports and fjords and could have been a nasty surprise for any enemy landing force.

United Kingdom

Together with United States, United Kingdom had most of the burden for defending and reinforcing Norway and Denmark. To this end, British Army fielded three different formations:

1. The United Kingdom / Netherlands Amphibious Force, a brigade-sized Marine unit with support helicopters and specially trained for operating in Norway

2. UK 1st Brigade, a mechanized formation that could have been assigned to Denmark or as an additional reinforcement to Norway.

3. UK 5th Airborne Brigade, a national strategic reserve to be used only in case of emergency.

As Falklands War showed just a few years before, Royal Navy was still a formidable force able to project power and support combat operations at considerable distance. In case of conflict against Warsaw Pact, the Navy would have committed at least one Aircraft Carrier and divided its forces among four difficult tasks:

1. Reduce Soviet air and submarine incursions across the GIUK Gap and against North Atlantic Lines of Communication

2. Transport and support UK / Netherland Amphibious Force in Norway

3. Transport and support UK 1st Brigade in Denmark or Norway.

4. Contribute escort to North Atlantic convoys.

Despite Royal Navy’s efficiency and excellent equipment, accomplishing all of the above was probably too much, and some difficult choices have to be made by NATO about where to employ British sea power.

Royal Air Force had a similar, demanding list of tasks to accomplish and could count on approximately twenty squadrons, with several Tornados and F-4s among them.

United States

US Marines started training seriously for an intervention in Norway during the ’70s. As in their tradition, they would have brought with them an impressive array of weapons systems including:

1. 4th Marine Amphibious Brigade, with three air and four helicopter squadrons, supported by a naval task force centred on Tarawa and Iwo Jima class Amphibious Assault Ships and several escort and logistical vessels.

2. 6th Marine Amphibious Brigade, with two air squadrons and four helicopter squadrons.

3. 2nd Marine Amphibious Force, with four air squadrons plus artillery and AA support.

US Army’s experimental 9th Infantry Division, structured as a “light” mechanized formation with a strong helicopter element, was another possible Norway reinforcement thanks to its (yet to prove) increased mobility and agile structure.

Air Force already had several F-111 and A-10 squadrons based in UK, mostly assigned to GIUK Gap defense and to strategic nuclear reserve but that could be diverted to Norway in case of need. Also, several reinforcement squadrons from CONUS would have arrived in UK or Norway during the first few days of the conflict. To this end, in 1974 US Department Of Defense signed an agreement with Norway for the creation of Co-located Operating Bases (COBs), enlarging and equipping several Norwegian airfields to support NATO squadrons.

US Navy plans for North Sea called for building up a force of up to three Aircraft Carriers, with three distinct operational phases:

1. Ensure North Atlantic Lanes safety by reducing Soviet Air and Submarine threat

2. Stabilize the situation in Norway

3. Counterattack in Norway and strike Soviet bases in Kola peninsula

Canada

Given their small size, Canadian Armed Forces were heavily committed to AFNORTH defense. Apart from an Iroquois class Destroyer included in NATO’s STANAVFORLANT forces, the Canadian Air Sea Transportable Brigade Group (CAST) was earmarked as Norway reinforcement.

Unfortunately, the Brigade’s disastrous performance during NATO Exercise Brave Lion in 1986 brought some doubts on its effective capability to deploy to Norway in an effective and timely manner. Despite that, it has been included but with a more or less improvised escort and little logistical support.

One thought on “Designer Notes Part 1, Deadly Northern Lights”

Comments are closed.