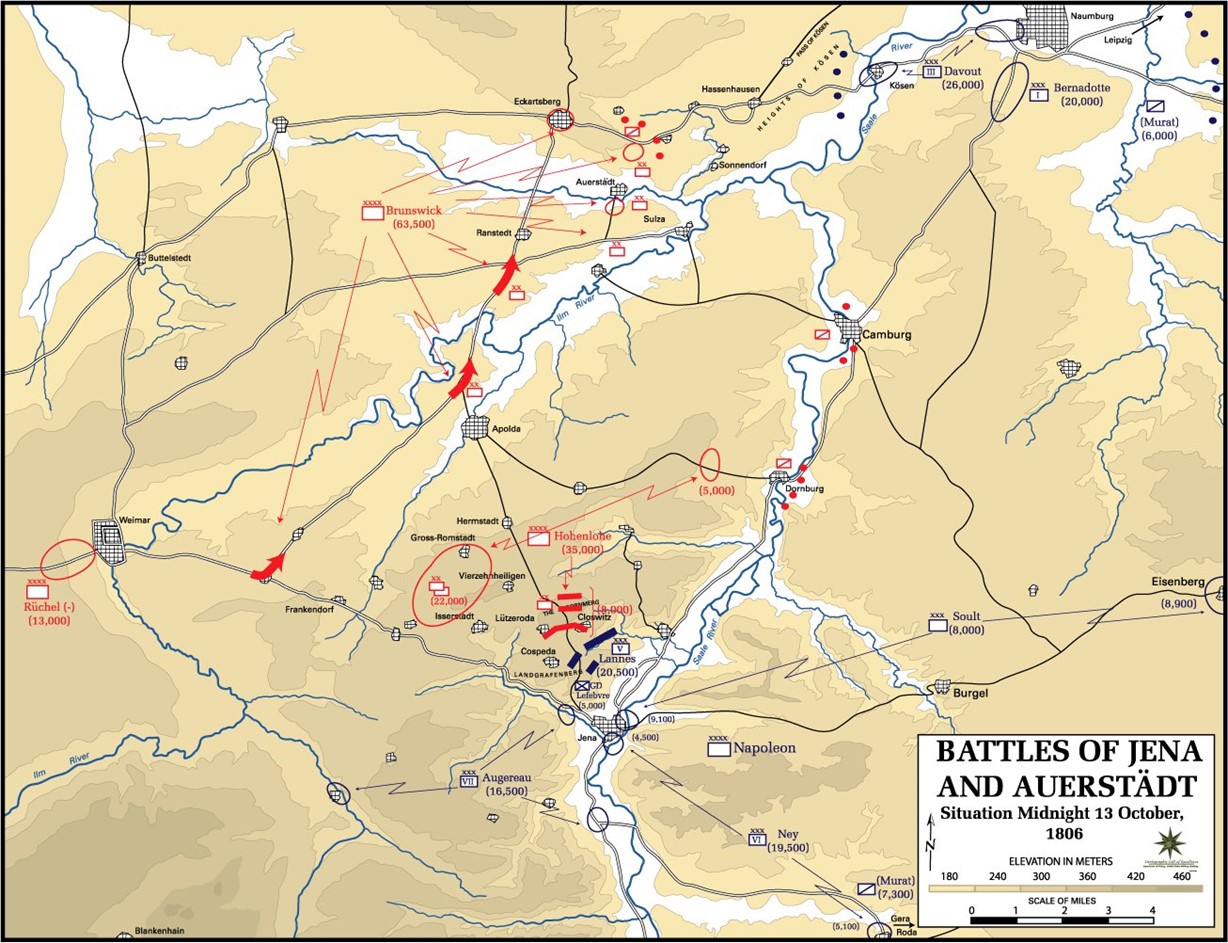

Overall situation

The creation of the Confederation of the Rhine, after the battle of Austerlitz, was badly accepted by the Prussians. These, blinded by the reputation which stick to their army since Frederick II, did not hesitate, on October 1, 1806, to give an ultimatum to France, summoning it to evacuate Germany. Napoleon reacted by directing the Grand Army towards the Main to meet the Prussian army which was concentrated in Saxony, sheltered from the mountains of Thuringia. The Berlin government, which thought it would benefit from the initiative against French people, busy concentrating their troops, had in fact already lost. Napoleon had preceded it and was ready before it.

The Emperor’s campaign plan aimed at seizing the enemy’s capital. After a first victorious engagement at Saalfeld, October 10, 1806, during which Prince Louis of Prussia perished, Napoleon pursued the Prussian army and learnt, on October 13, that he joined her not far from Jena . He therefore sent Louis-Nicolas Davout and Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte forward, ordering them to cross the Saale to go to Apolda and Weimar and cut off the retreat of the enemy. According to his calculations, while he himself would face the bulk of the Prussian army, his marshals would have in front of them only a rear guard. The opposite was going to happen.

Prelude to the battle

On the night from the 12th to 13th of October 1806, the Prussian command decided to withdraw towards the Elbe. On the morning of the 13th, the army of Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg, left Weimar for Magdeburg. The vanguard, with whom the King, the Duke of Brunswick, and General Wichard Joachim Heinrich von Möllendorf were marching, spent the next night near Auerstaedt . The next day, Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher took charge of Kösen at the head of 28 cavalry squadrons and with the support of Friedrich Wilhelm’s division Carl von Schmettau. This one had to hold the heights of Kösen while the army of Brunswick was going to pass the Unstrut to Freiburg [Freiburg] and to Laucha. It would then keep this position pending the arrival of the troops of Frederick Louis Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, who had to follow.

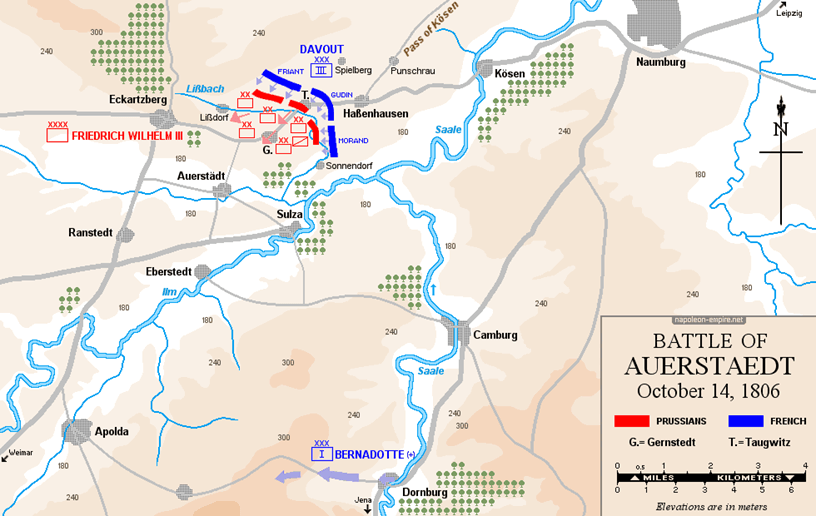

At dawn on October 14, Davout left Naumburg [Naumburg an der Saale] heading south-west with the 26,000 men of his only III Corps. Bernadotte, who hated him and jealousy, refused to join forces. The commander of the Third Corps offered to leave his colleague the command of their joint-venture, nothing worked. Around 6.30 am, the division of Charles-Étienne Gudin passed the Saale on the bridge of Kösen . It then crossed the path of the same name and started climbing the plateau on which was standing the village of Hassenhausen, 7 kilometers from the river. As in Jena at the same time, an opaque fog covered the countryside. A detachment of chasseurs on horseback, sent as a scout, delivered the first skirmish of the day by falling unexpectedly on a troop of Prussian horsemen. These were part of Blücher’s detachment. First victorious, the Prussians were soon arrested and driven back by the French infantry squares.

First hours: Resistance from the Gudin division

Against Brunswick’s opinion, who wanted to wait for reinforcements, the king chose to follow Moellendorf’s, who pointed out the weakness of the enemy forces and advised to reject them without further delay in the path of Kösen. Schmettau and Blücher accordingly received the order to attack in force. Although they still had only Gudin’s division and a regiment of mounted chasseurs in front of them, their offensive broke on the 25th Line Regiment, which stopped the first enemy column, sew disorder and seals, and took two of his batteries.

Davout, however, arranged for the upcoming battle. He positioned a regiment in the village of Hassenhausen , two others on the right of the village on a small eminence, a fourth on the left .

While Schmettau’s division was woring on Gudin’s skirmishers, Blücher tried to surprise the French with fog. He passed his squadrons between Spielberg and Punschrau to attack their right flank and their backs. But the regiments against which it clashed were formed in squares by battalions and hold good. Encouraged by their leaders who went from square to square between the successive charges of the enemy, French infantrymen even managed to repel their attackers. These, disgusted by the heavy losses they experienced, came to abandon the fight. While the bulk of the Prussian cavalry retreated behind Schmettau’s division, some of the squadrons who suffered the most flee to Eckardtberga. The French hunters, till then held in reserve, started the pursuit.

In the meantime – it was then about eight thirty – the division of Leopold Alexander von Wartensleben, strong of ten battalions, burst on the zone of combat. Brunswick sent him immediately to support Schmettau’s division, which was fighting, at that moment, on the slopes of the hillocks overlooking Hassenhausen. Faced with this combined attack, the division Gudin, was in great danger of being submerged.

Arrival of the Friant Division

Luckily, this was the moment chosen by the division of Louis Friant to arrive on the battlefield . Davout immediately positionned it on the north hill, where it prolonged and relieved Gudin’s right. Soon, Friant was even able to launch a violent assault on his vis-à-vis, which he pushed back to Spielberg.

On the opposite side, the situation was more critical. The regiment which alone composed the French left got attacked both from the front and the flank by forces far superior to its own. Seeing him in great danger, Davout did not hesitate to detach two regiments from his right wing, where the situation was at its best. The first was sent to support the left wing, the second took solid position within the village of Hassenhausen. It was only time, because Brunswick soon received the reinforcement of a new division, that of Prince William of Orange (Wilhelm Fürst von Nassau-Orange-Fulda, the future king Guillaume Ier of the Netherlands) lining up about 10,000 men. It was then between 10:30 and 11:00.

With this new mass of combatants, Brunswick decided to try a new effort south of Hassenhausen, where the French left seemed – rightly – much less solid than the right, which had resisted until then all attacks. The maneuver he designed aimed to overflow Davout from the south and cut his retirement to the Saale. The Prussian general-in-chief then sent the infantry of the Orange division to support the bulk of Schmettau’s division, these two troops pressing their pressure on the village and the northern nipple. At the same time, the entire Wartensleben division, reinforced by six battalions taken from the Schmettau division and the cavalry of the Orange division, was launched to attack the two French regiments of the southern wing. Submerged, they had no choice but to retreat, partly in the village, partly in the hollow roads that led to it.

The Morand division joined the fight

The situation became dangerous for Davout’s third body when the division of Charles Antoine Morand entered the fray by the French left. Its burst, at around 11 am, broke the impulse of the enemy infantry. Wartensleben was repulsed. The Prussian cavalry of Prince William of Orange, with 10,000 horsemen, then attempted to load the French columns, as did that of Blücher a little earlier and without more success. The French regiments were immediately formed into squares by battalions and repelled them. Morand immediately returned to the offensive.

Meanwhile, at the center of the scheme, the struggle for control of the village of Hassehausen, considered by the two generals in chief as the key to the battle, continued with greater vigor. In this fierce defense, the French regiment occupying the front line lost half of its strength. However, the Prussian attacks were becoming less and less sharp, as the fire of the French tirailleurs cleared the lines of the attackers. As in Jena at almost the same time, Prussian battalions had to be forcibly sent back to fight by their officers. Brunswick, to revive their courage, stood at the forefront of a battalion of grenadiers and walked with them towards the village. A gunshot hurt him deadly. General Schmettau killed, Marshal Möllendorf wounded, it was half of the high command of the Prussian army which was suddenly unable to fight. In addition, the Friant division in the north was pushing its vis-à-vis, putting the Schmettau division in danger of being overwhelmed. To avoid it, it ended its attacks on Hassenhausen and won. Soon, it was the entire Prussian front that surrendered and retreated nearly 1500 meters in order to reorganize itself.

First Prussian retreat

The new battle line was located southwest of Hassenhausen. The Prussian left was in Poppel, the center in Tauchwitz [Taugwitz] , the right in front of Rehausen [Rehehausen] . The King of Prussia personally commanded his army. He hesitated a moment between going back to the attack or retreating. If the three divisions that had fought so far were already well underway, two others were about to join them. The king could throw everything on the French or use the last arrivals to cover the retreat. While he was deliberating, Davout was busy assembling his own troops. The fight paused.

The French marshal soon put an end to the procrastination of the King of Prussia by himself going on the offensive. On the left, Morand’s division advanced on Rehausen; in the center Gudin left Hassenhausen to clear the village of Tauchwitz ; on the right, Friant attacked that of Poppel where a thousand Prussians put down arms. The Prussian army ad to back off once again, in good order, however, always towards the southwest , so Auerstaedt.

Intervention by the Kalckreuth division

Halfway to this village, Friedrich Adolf von Kalckreuth’s army corps was located around the hamlet of Gernstedt, on the right east side, the left west side as far as Lissdorf. This reserve was composed of two large divisions of infantry and twenty-five squadrons of cuirassiers and dragoons, to which had just been added, at the end of their retreat, many of Blücher’s cavalrymen. The position was good, overlooking a valley at the bottom of which the enemy would cross a stream, the Lissbach , before going back to the Germanic troops. The numerical superiority of the Prussians, once Kalckreuth’s corps united with the retreating divisions, would be of the order of two against one. Faced with units that had been fighting since early morning, the chances of a success likely to erase the failures suffered so far were not slim. Blücher vigorously advocated this solution and proposed to prelude it by a large cavalry charge. He was already organizing it when Frederick William III returned to his initially favorable decision.

Prussian retreat

The King of Prussia, was, in fact, demoralized by the loss of the general-in-chief of his army, the debacle of his infantry, and the fiasco of his cavalry, judged hitherto unbeatable and unequaled. Moreover, nothing that was happening in Jena had yet come to his knowledge, hope had allowed him to repair soon the defeat of the day in another battle, given once the junction with Hohenlohe’s army restored. It was ultimately the solution he chose. Around 2 pm, he sounded the retreat.

Shortly after, Davout’s army appeared in front of the Kalckreuth reserve, left behind. Friant division, on the right, overflew the opposing left flank formed by the division of Alexander Wilhelm von Arnim, which was simultaneously attacked frontally by the Gudin division. The Prussians were pushed back to Eckartsberga, leaving behind 22 cannons. On the other wing, the Morand division springed from the Rehausen valley to assault the flank of Johann Ernst von Kühnheim’s division. Despite a harsh resistance, the latter finally had to retreat, as well as a large fraction of the cavalry.

Kühnheim rallied his troops in Auerstaedt and tried to maintain himself there. Davout had the village bombed with shells. The fire forced the Prussians to flee. The fight stopped then and Davout installed his encampment close to the village in flames.

From retreat to meltdown

At this moment, the battle had already made 10,000 Prussian victims, dead and wounded together. 3,000 more fighters had fallen into the hands of the French. The rest retreated in fairly good order, in the direction of Weimar, by Auerstaedt, Rudersdorf and Willerstedt. But, to the south-west of Apolda, the vanquished of Auerstaedt were reunited with those of Jena who fled before the cavalry of Joachim Murat. The mixture of these routed bodies caused an irreversible disorder. Panic seized Prussian soldiers who threw their weapons to flee more comfortably. Every organization abolished, the fugitives ran at full speed towards Weimar in the midst of the horses of their pursuers, who cut them with sabers and entered the city with them. Survivors were going to continue their journey to Erfurt or Buttlestedt.

King Frederick William scarcely reached Sommerda, about thirty miles from the battlefield, with a few squadrons. Queen Louise of Prussia, on the other hand, had to leave Weimar about four o’clock in the afternoon, at the first echoes of the defeat.

Consequences

This defeat, combined with that of Jena, suffered on the same day by the rest of the Prussian army, resulted in the almost complete dissociation of the latter. The discouragement was such among what remained of troops to Frederick William III that fortresses and cities would capitulate in the following days in front of simple regiments of hussars. Three weeks later, on October 27, Napoleon entered Berlin, making the Third Corps and Davout go before him, in tribute to the extraordinary victory achieved by them against troops two to three times more numerous. Hohenlohe and Blücher would take up arms soon after.

On November 30, 1806, an armistice was concluded. The war would continue in Poland, the King of Prussia now placing all his hopes in the intervention of Tsar Alexander I. The latter would hardly justify his confidence in sacrificing his ally after his own defeat: the treaty signed at Tilsit on July 9, 1807 would cost Prussia half of its territory, 5 million inhabitants and almost all of its strongholds, with the payment of a war indemnity of 120 million francs.

Bernadotte leaned, to refuse to join Davout, on the very text of the orders transmitted to him by Louis-Alexandre Berthier. “If Marshal Bernadotte is with you, you may walk together, but the Emperor hopes he will be in the position he has indicated to him at Dornburg. ” Bernadotte indicated that he intended to place himself where the Emperor hoped he was. But on the evening of the 13th, he was so far away – he was in Naumburg, six leagues from his goal – that the movement he was considering was especially likely to prevent him from participating in the events of the next day, which was clearly contrary to the will of Napoleon. The latter, it seems, went so far as to consider deferring his marshal to a council of war for disobedience to his orders.

https://www.napoleon-empire.net/en/battles/auerstaedt.php