Army and State

After the battle of Chaeronea, Philip was at the zenith of his career. In he wanted to surpass himself, he would have to leave Europe and attack the Achaemenid Empire. What had made him so powerful?

It’s useless to deny that he was lucky. During the first years of his reign, the Greek powers in the south simply underestimated the man who appeared to be just another Macedonian leader. It was only after the outbreak of the Social War in 357 that Philip showed his true intentions when he captured Amphipolis and Pydna. But then, intervention had become impossible. Athens lost much of its empire in 355, and immediately, Thebes got into trouble in the Third Sacred War. Sparta had been in decline since the battle of Leuctra (371). At the same time, the king of Persia was more interested in Egypt. There was every opportunity for an ambitious Macedonian leader to expand his power.

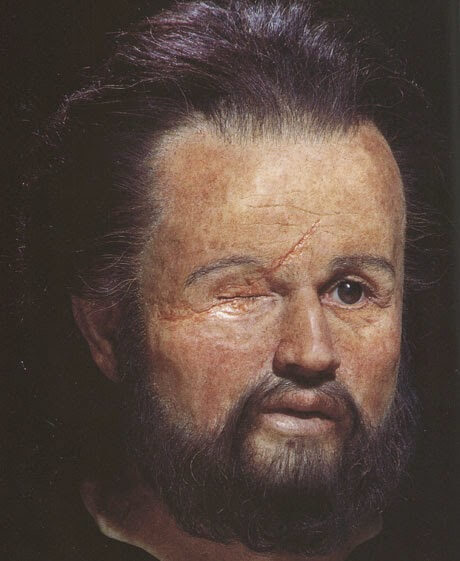

This being said, we can only add that Philip was a great general, a visionary statesman, and very clever. A man, also, who seems to have lived for his ambitions and had no real private life. Except, perhaps, for his final marriage, every woman in his life served a political aim. The result was the most powerful state Europe had ever seen.

One of Philip’s greatest ambitions (and successes) was organizing an army that was loyal to the king, and not to the Macedonian aristocrats. To achieve this, he took several measures. In the first place, he created new noblemen, so that the privileges became more common and less prestigious. The old aristocrats were compensated with dubious new privileges and land. This land was typically given in one of the newly conquered parts of Macedonia, so that the nobleman could no longer spend all his time in his native county, and loosened the ties with his own people. Among the privileges was the right to send one’s sons to the royal court, where they would serve as pages of the king. The boys received an excellent education and learned to know people from all over Macedonia. At the same time, they served as hostages and guaranteed the loyalty of their fathers.

The old nobility being less strong, Philip could create a new aristocracy. On massive scale, he gave out land and military offices. The people who received land were to serve as cavalry men, and were called Hetairoi, “companions”. They were not unlike the Prussian Junker class. When Philip became king, there were about 600 companions; when he died, more than 3,000. Many people had been included who were not native Macedonians: for example, Paeonians, Thessalians, Thracians, and Greeks. In this way, the Hetairoi were some sort of melting pot. When Alexander accepted Iranians among the companions, he simply continued his father’s policy.

Unlike the common practice in the Greek world, Philip used these men for frontal attacks. In a wedge-shaped formation (“like a flight of cranes”, in the words of Polyaenus), they attacked their enemies. The commander was in the first rank, and casualties among Macedonian officers were higher than in Greece, and it is no coincidence that Philip was lame at the end of his life. On the other hand, the cavalry men were inspired by this type of leadership and fought better.

Non-aristocrats fought in the Macedonian phalanx of heavily armed infantry. The Pezhetairoi (“feet companions”) had been founded by Philip’s brother Alexander II (above). Always, these soldiers, often called hoplites, had been armed with a spear with a length of about four meters, a sword, shield, helmet, shinguards, and armor. They fought in close battle arrays, which could not be defeated as long as they kept their formation intact. However, when their array was shattered, the losses could be terrible.

Philip improved the force of the phalanx by making it deeper and giving the foot companions a ‘lance’ of six meters instead of a spear. The lance had to be carried with two hands and therefore, the Macedonian shield was less heavy. The sheer offensive power of the six battalions of 1500 men was the unit’s best defense.

To be strong enough to force away its opponents, a phalanx had to be many rows deep; and to prevent outflanking, it had to be many files wide. Many people had to be trained, which cost a lot of time and was expensive. The soldiers also had to learn to carry their own armor, tent, and food, to make them less dependent on mules, and therefore faster than other armies. All this took time, but the result was Europe’s first professional army: large, well-trained, heavily armed, fast, and invincible.

Except for the Companions and the Foot Companions, Philip created or reorganized other units. There were light-armed spearmen and Cretan archers, who were used to break the rows and files of enemy phalanxes. The Agrinians were very light troops, often used in the mountains, whereas the Hypaspists (“shieldmen”) appear to have been some sort of elite hoplites. And of course, there was the artillery of catapults and a group of engineers, which were used during sieges. During the siege of Perinthus in 340, the Macedonians used a tower that was 30 meters high, and Alexander would order the construction of moveable towers on wheels during the siege of Tyre (332).

Although this army was almost invincible, and although it appeared to be permanently active, it was in fact less often used than it seemed. Philip understood that only soldiers that are alive can inspire terror, and his men knew that their king would not unnecessarily risk lives. Philip may have agreed with the words of general Patton that loyalty from the top down is more important for an organization than loyalty from the bottom to the top, and Philip had the wounds to show that he shared the dangers with his men.

It was foolish to attack a city if you could also employ the twin weapons of threatening to attack & hiring a traitor. So he bought Olynthus, bribed Phocian officers, and summarized his policy with the famous words that walls could also be scaled with gold. The king of Persia, who used his silver and gold for the same purposes, could have said the same, and would also have understood the extravagance of Philip’s parties. The guests gave him important information, and when the Macedonian host sent them home with precious presents, he knew that one day, they would help him. It was expensive, but it worked.

Meanwhile, the Macedonian state remained underdeveloped. Philip was the center of everything. It is highly significant that the coins bear the legend Philippou (“of Philip”), whereas the coins of the Greek cities had legends like Athenaiôn (“of the Athenians”). But there were no coins “of the Macedonians”. Treaties were concluded by Philip, not by the Macedonian state. The apocryphal words of the French king Louis XIV, L’état, c’ est moi (“The government, that’s me”), might have been spoken by Philip.

One of the results of this concentration of power was the impossibility to find reliable generals, who might have independent commands. The soldiers remained loyal to commanders, not to an abstract state. Philip once said that he envied the Athenians, because they could every year elect ten generals, whereas he had found only one, Parmenion. This is often seen as a compliment to Philip’s most trusted officer, who was a real commander, but there’s more to this famous quote. It is a fine illustration of the difference of a real, developed state, and a pristine state like Macedonia.

Philip could modernize other sectors of Macedonian society. The cities, whether they were old Greek colonies like Amphipolis or new settlements like Philippopolis, were very important because they were centers of Greek culture and a more advanced economy. The problem, however, was that cities were usually independent, and this did not fit well in the autocracy that was Philip’s Macedonia. As we already noticed above, Philip imitated the Persian solution: he left the cities their independence and appointed officials that were to report about what happened in the cities (spasaka, episkopos). In several towns, garrisons were stationed.

So, Philip created, in the almost twenty-four years of his reign, a new Macedonian state, army, and society. Of course, the times were favorable, with the Greeks creating their own destruction and the Persian king looking to Egypt. On the other hand, a man with less personal courage, less diplomatic skills, and less talent for organizing a kingdom, would have achieved less.

It was a brilliant achievement, but it had one fatal flaw. The state created by Philip was exactly that: a state he had created. People remained loyal to the king and not to an abstract state. Philip could bring the Macedonian society from the level of a tribal organization to that of a pristine state, but never beyond this point. Macedonia was like Cyrus’ Persia and Charlemagne’s Franconia, in which the ruler overcame opposition by continuous conquest, and the sharing of booty. Macedonia had to expand or implode.

Therefore, Philip’s kingdom was always growing, and sooner or later this expansion would interfere with the vital interests of the Persian empire. As it turned out, this moment was the Perinthus* incident. Here, he had to admit defeat, and this is why he was to provoke a new conflict with the Greek cities, which he defeated once and for all at Chaeronea.

*The siege of Perinthus (340-339 BC) was an unsuccessful attempt by Philip II of Macedon to defeat a wavering ally, and was conducted alongside an equally unsuccessful siege of Byzantium. Both sieges took place in the period just before the Fourth Sacred War.

Perinthus was officially allied with Philip, and in 340, when Philip decided to support his allies in the Chersonese against the local Athenian commander, he asked Perinthus and Byzantium to help. Both cities refused to offer support, and Philip decided to reduce them to obedience before dealing with the Athenians.

Perinthus was a difficult target for a siege. The city stood on a promontory, connected to the land by a 200 yard wide heavily fortified isthmus. The coast was protected by cliffs, making any amphibious assault impossible. The promontory was covered by houses rising steeply on terraces, and the promontory was protected by strong fortifications.

Philip had an impressive siege train, created by the Thessalian siege engineer Polyeidus. He built 120ft high siege towers, topped with catapults, battering rams and mines, and battered the outer walls.

The defenders were supported by Byzantium, which sent men and catapults. The Athenian fleet, under Chares, managed to keep the Macedonian fleet out of the Propontis, so the defenders had control of the seas around the city. The Persians also sent help, a force of Greek mercenaries under the Athenian Apollodorus.

Philip decided to send part of his army to escort the fleet through the Hellespont. Probably at about the same time he sent a letter to Athens, condemning the city’s hostile attitude and appealing for restraint. This was never likely to have any impact at Athens, but any chance was eliminated by the progress of a Macedonian army along the coast of the Athenian territory in the Chersonese.

Although this did allow Philip to get his fleet into the Propontis, that didn’t make any difference. The defenders were now getting support from the Persians, after Artaxerxes III ordered his satraps to send aid. Reinforcements and supplies reached the city, and the Macedonian fleet was unable to intervene.

After several weeks of active siege work the Macedonians finally breached the outer wall, but to their dismay they discovered that the defenders had walled up the gaps between the first line of houses, creating a fresh, almost equally strong line of defences.

Philip now decided to shift his attention to Byzantium, in the hope that the aid she had sent to Perinthus would make her vulnerable. He left part of his army to blockade Perinthus, and moved the rest of it to attack Byzantium. Early in this siege he intercepted a Athenian merchant fleet, capturing 180 Athenian ships. This move finally triggered a declaration of war by Athens, and the Athenians provided open support to the defenders of Byzantium.

Philip continued with both sieges across the winter of 340-339 BC, but after one last failed assault on Byzantium decided to abandon both and instead carried out a campaign in the Balkans.

Perinthus was soon forced to come to terms to Philip, probably after the Athenians and Thebans suffered their great defeat at the battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), but retained some independence, and continued to issue her own coins.

Rickard, J (7 February 2017), Siege of Perinthus, 340-339 BC , http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/siege_perinthus.html

Nice short piece. 🙂

🙂