As we continue a brief series of posts about the lead up to the Battle of Issus one thing that has always struck me as interesting is the ability for these armies to find each other and then get to a location of one or the others choosing.

In this case Alexander literally lucks out. As Darius had grown impatient [see prior post] and moved his massive army to engage Alexander after misunderstanding the rationale for Alexander’s delay.

But with both sides making moves to attempt to engage or cut off the other who could march the farthest and be in good shape to fight upon arrival may well have a significant advantage.

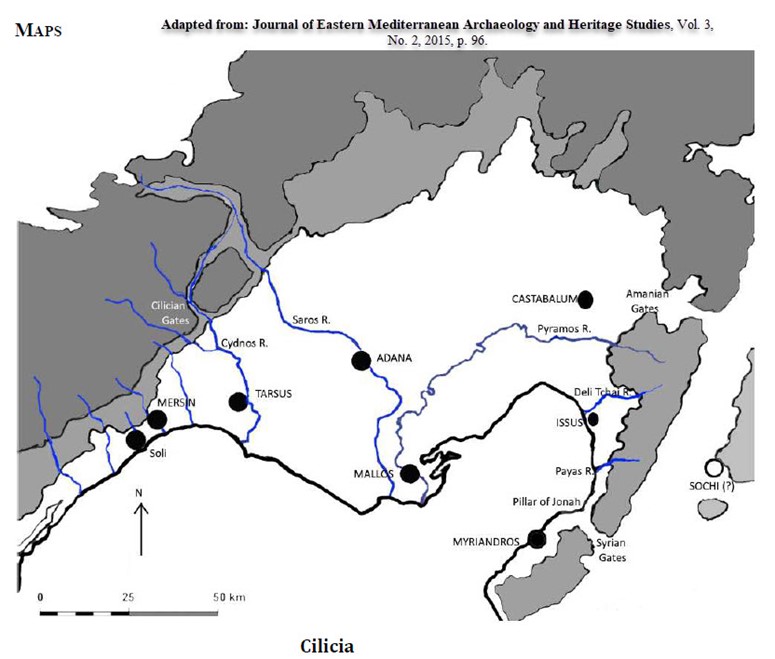

Engels wrote a book called AoG and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army where he put significant effort into identifying locations understanding logistical challenges. Our author we are quoting here references him extensively. Armies in these times could carry about three days rations with out resorting to literally thousands of pack animals which raise the feed carrying requirements exponentially. At its fastest the Macedonian army moved 19 miles a day.

Toohey picks up this thread:

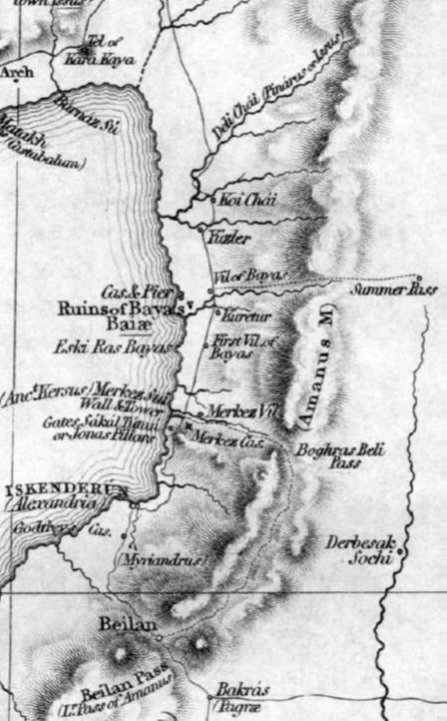

March time was the most compelling factor raised by Engels in support of his case for the

Pinarus to be identified with the Payas. It was an elegantly simple observation that makes

perfect sense when you think about it. Where an army has to march through a pass, the number

of troops that can march through over any unit of time is directly limited by “the narrowest

constriction of the pass”. In the case of the Pillars of Jonah, at its narrowest “no more than four

infantry or two cavalry horses” could pass abreast at a time. On that basis, Engels argued, it

would have taken 7½ hours for Alexander’s army to march through the pass.420

Because of that delay, Engels argued, Alexander could not have reached the Deli River until

half an hour after sunset at the earliest. But he could have reached the reached the Payas by 4:30

pm, half an hour before sunset.421

Engels based his calculations on an estimated army size of 40,864 infantry and 6,280 cavalry

– 47,144 men in total – a figure comparable to Polybius’ estimate of 47,000 men for the size of

Alexander’s army at this time.422 Hammond, by contrast, contends that Polybius’ figures were

“wide off the mark”, and that, based on the units listed by Arrian, Alexander’s army may have

been “little more than 30,000” men. Such a figure would make the size of Alexander’s army

“compatible with the size of the battlefield as reported by Callisthenes”.423 If Hammond’s estimate is

correct, this would reduce the time required for Alexander’s army to descend the pass

to as little as 4¾ hours.424

So Engels may have been mistaken in his estimation of the time it would take Alexander’s

army to traverse the narrow pass. This does not, however, seriously undermine Engels overall

contention, since neither makes any allowance for time lost in the subsequent redeployment of

the army into line, discussed below.425

And if Arrian neglected to mention any units, then Hammond himself may have underestimated

the size of Alexander’s army.

Either way, from the bottom of the pass the army still had to redeploy and march a further

11kms to reach the Payas. At the same time, the Persian army had a 10kms march to reach the

river and then deploy their forces for battle. With the pass delaying Alexander, that still gave

them time enough to reach the river and deploy well ahead of Alexander.

So both armies end up at the Pinarus river within some hours of each other.

Ancient authors comment on the doubling back and marching through the Gates of Jonah

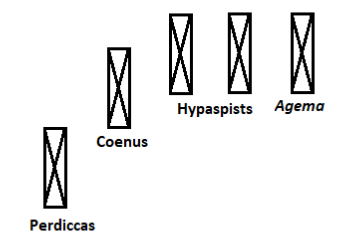

But Arrian goes on to note that as the land began to open out onto the still narrow coastal

plain, Alexander began to redeploy “his column continuously into a phalanx, bringing up

battalion after battalion of hoplites24, on the right up to the ridge, and on the left up to the sea”.25

This is in general agreement with Polybius, but Arrian’s text adds the additional detail that the

deployment was continuous as the plain widened.

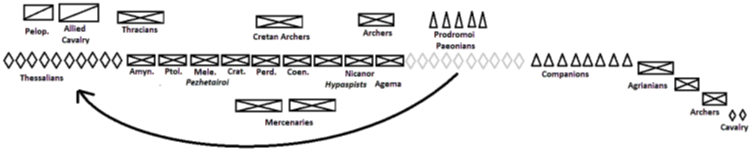

Arrian adds that the “cavalry had so far been ranged behind the infantry”, which suggests

he would then describe how the cavalry deployed as the army “moved forward into open

ground”. But instead, he gives a detailed account of how Alexander then deployed the infantry

into a line of battle order, with no reference to the cavalry beyond noting that Parmenio was

given command “of the entire left wing”.

Now remember that Engels had calculated it would take 7½ hours for the whole army to

march through the pass. And somewhere not far ahead the Persians were waiting, if not already

advancing to meet the Macedonian army. Alexander could not afford to have his first units

march out to a suitably wide place and wait for the rest of the army to catch up.

Instead, I would suggest that as the first company of infantry emerged from the defile, they

continued to advance while they each reformed as soon as possible into a thirty-two deep

column. Then, as the land widened to accommodate more than one column of that size they

continued to advance at a slower, probably half, pace, while at the same time stepping to the

right to allow room for the company coming after them to take their place beside them as they

continued their slow advance. And this would have continued, unit after unit, until the full front

line of infantry was deployed.

Such a deployment is consistent with both Arrian’s account. And it is also consistent with

the Polybius/Callisthenes’ claim that, when they reached open ground Alexander, first “reformed

his order” into a thirty-two deep phalanx.26 And that he then led the army forward in an

extended line,27 if we accept that this was a line of columns marching side by side with gaps

between them sufficient to allow them to negotiate any obstacles in their path.

Remember, the Pinarus would have been about eleven kilometres from the base of the

pass.28 No army could march such a distance in an extended line. Polybius was right on that.

But the march could be done with relative ease in a line of parallel columns.

… A significant part of the army, including the “Immortals”,48 must have been

held back in reserve either at Babylon or Sochi, or both. We know this because of the size of the

army Darius was able to assemble at Gaugamela after his defeat at Issus.

According to Arrian, Darius advanced to the river Pinarus the day after he had taken Issus

10kms to the south.49 Now, as Engels has noted, “standard march speed for infantry” is 3

miles/4.8kms per hour over open terrain, and 2.5 miles/4kms per hour over difficult terrain.50

This means that it would have taken from two to four hours for the Persian army to reach the

Pinarus, depending on the difficulties of the route. And, as Engels makes clear, that only applies

to the leading units of the army. Depending on the size of the army, several hours more must

then be allowed for the rest of the army to catch up, once the lead ranks have halted.51

Just when the Persian army left Issus is not stated. It is reasonable to assume, however,

that scouts were sent out in advance of the army who sent word back to Darius that the

Macedonian army were marching down the Jonah Pass, and had started to assemble and advance

on the plain below.

Whatever its actual size – an issue to be considered shortly – the Persian army was large

and cumbersome. Given the subsequent course of events, it is reasonable to conclude that, on

receiving that news, Darius decided to stop his advance and assemble his army for battle at the

Pinarus.

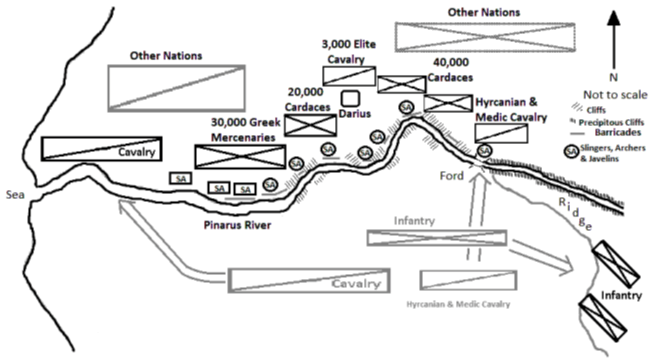

Callisthenes, via Polybius has presented the simplest version of the Persian battle front.

From shore to mountains, the Persian line runs as follows, 30,000 cavalry, 30,000 infantry

(Greek Mercenaries), and from there on, peltasts.52

Arrian gives us some more details. As already discussed, Alexander began to deploy the

phalanx into battle formation on the march to the Pinarus.53 When Darius heard of Alexander’s

approach, he sent a body of 30,000 cavalry and 20,000 light infantry across the river to screen his

own deployment along the north side of the river bank.54

The core of the Persian battle line, in Arrian’s account, consisted of a force of 30,000

Greek mercenary hoplites, flanked on either side by units of Cardaces (Persian heavy infantry)55

together totalling 60,000 men.56 Behind these were massed a body of light and heavy troops that

were rendered useless by the very way in which they were deployed.57 20,000 men are also

reported to have been posted on a ridge (across the river) against Alexander’s right.58 These are

almost certainly to be identified with the 20,000 light infantry in the advance force. No mention

is made of them when Arrian’s later reports on Darius’ recall of the cavalry, most of whom were

station stationed on the right wing. (Some were sent to the left wing, but most were recalled for

lack of space).59 Curtius also recorded that 20,000 men had been sent across the river to

“oppose” Alexander and, if unsuccessful, or unable, they were then to retire to the mountains and

try to place themselves behind the enemy.60

“Darius himself held the centre of the whole host, the customary position for Persian

kings”.61

Probably, we should take it from this that when Darius recalled the cavalry, the infantry

with them were told to move instead to the mountains on their flank, in the hope that they would

at some time have the opportunity to attack either Alexander’s flank or rear. And even if they

were not able to do that, their position would require Alexander to dispatch some of his army to

watch them. In this way the forces available to him for his attack would be reduced.

Finally, it must be noted that when Alexander launched his attack at the ford he came

under fire from archers, suggesting that they had a place at the front of the Persian left wing as

well.62

The conflict that we find in these accounts mean that the Persian battle line can only be

very roughly sketched. But when examined carefully there are number of points of concurrence.

The right wing was held by a large body of cavalry – up to 30,000 men (Polybius and

Arrian). Arrian, Curtius and Callisthenes all agree that there were also 30,000 Greek mercenary

hoplites near the centre.66 Most modern scholars shy away from this figure,67 but from

references in our sources at least 10,000 seem to have survived the battle.68. So the number of

mercenary hoplites was clearly greater than 10,000, and quite possibly, much greater.

The 60,000 Cardaces mentioned in Arrian matches the 20,000 ‘barbarian’ plus 40,000

unspecified infantry included in Curtius.69 He may have been unsure how best to translate

Cardaces into Latin, which is why he left his designation of them vague. They are clearly the

same men, and there is only a minor difference regarding their placement. Arrian placed them

either side of the mercenaries, while Curtius placed them next to the mercenaries to either side of

Darius. Darius was in the centre, defended by his own elite cavalry.70 Curtius’ placement of the

Hyrcanian and Medic cavalry is also compatible with Arrian’s statement that when they cavalry

sent across the river were recalled, some were sent to the left wing, but most of these were

recalled because of lack of space.

This is important. As Berg/Hermans battle setup does not account for either the recall of the Medic Cavalry nor that any at all were in place on Dariu’s left. So we will add some here to account for this in the final setup.

Both Arrian and Curtius also agree that there were Persian troops left in the hills or ridge

on Alexander’s right in the hope of possibly turning his line. These may well be the slingers and

archers Curtius placed next to the cavalry, accidentally including them with the cavalry when the

advance guard was pulled back across the river. That would mean there was a double up between them

and the men sent to the hills to the east in Curtius’ account. Certainly, the numbers (20,000) match.

This leaves only the 6,000 slingers and javelin men that Curtius placed in advance of the

Persian line, who Arrian could have easily overlooked. They were probably placed along that

one kilometre plus stretch of the river where Devine describes the banks as being steep but

traversable for infantry, but not cavalry. (See Topology, Chapter 4 above.) This will have been

where Darius, as Arrian reports, also erected stockades in those parts which were not

precipitous.71 These light troops will have played an important role in the early stages of the

battle, as shall be discussed in due course.