Designer’s Notes by Fabrizio Vianello

Have you ever thought a subject had no more surprises, only to find a bunch load of new, unexpected layers the moment you revisit it? Well, it happens to me all the time, and yes, of course by now I should know better.

In a Dark Wood has been no exception. Like its predecessors, it introduces several intriguing new dimensions to the NATO-Warsaw Pact conflict – or, depending on your perspective, forces you to face more grim realities about warfare.

Being the fourth module in the series, these Designer’s Notes are not going back to discuss the basics; A full coverage for that can be found in the Less Than 60 Miles Extended Designer’s Notes, available for download on TRLGames.com. What we will cover here are the peculiarities of this sector of the Central Front, and in-depth considerations about some of the armed forces involved.

More detailed info on In a Dark Wood can be found on our official site, and by now you should know the drill: Report for Duty to info@TRLGames.com to reserve your equipment!

The Battleground

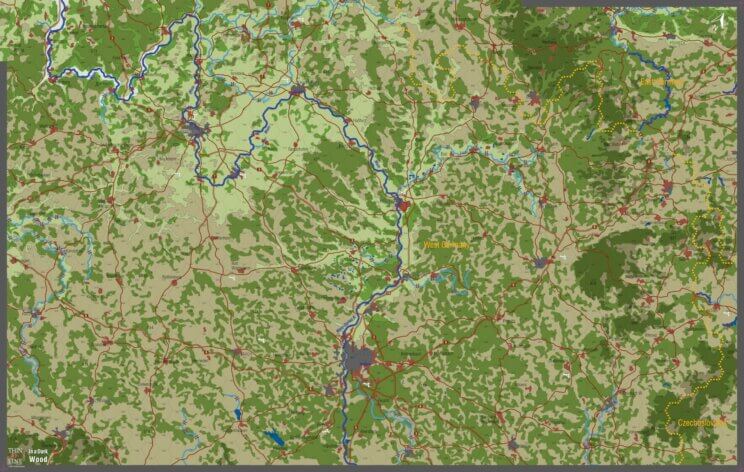

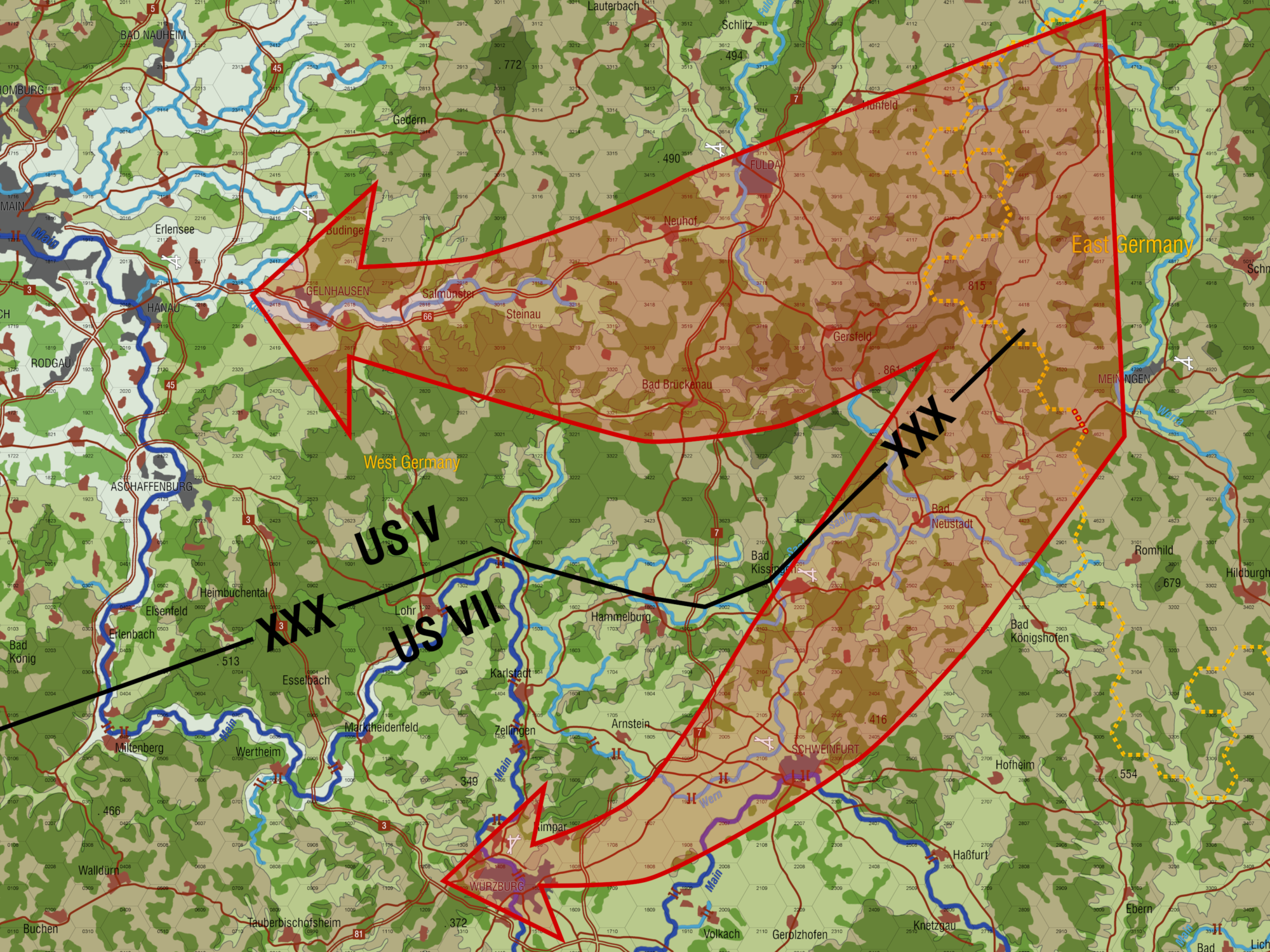

The map covers the whole US VII Corps Area of Responsibility, plus a slice of WG II Corps area to the south. Considering the layout of the Inner German Border (the “this is not an international border” division of Germany), this translates into approximately 200 km of front to handle, one of the longest sectors defended by a single NATO Corps.

No Thanks, We Don’t Need More Trees

A cursory glance at the map is more than enough to realise that the terrain in this sector is far from ideal for large-scale mechanised warfare.

First, hills above 400 meters create a major obstacle, with the highest peaks situated exactly where the Warsaw Pact forces least want them—right along the Iron Curtain or just a few kilometres to the east.

Second, dense forests are practically everywhere, with the only exception of an area in the proximity of Wurzburg and Schweinfurt.

Further complicating the situation is the Main River, whose winding path divides the region and adds another layer of difficulty for forces moving in either direction.

Setting aside the picturesque German landscape, the road network offers little help. Despite being extensive, it primarily runs north-south, providing only limited options for the eastbound movement required by the Warsaw Pact and the westbound routes NATO needs to bring in reinforcements.

While these geographical features generally favour the defenders, they can also pose challenges: the rough terrain forces NATO reinforcements to rely heavily on roads, and the limited number of west – east routes could lead to traffic congestion, making Warsaw Pact interdiction and bombardment particularly effective.

The Shortcut to Würzburg

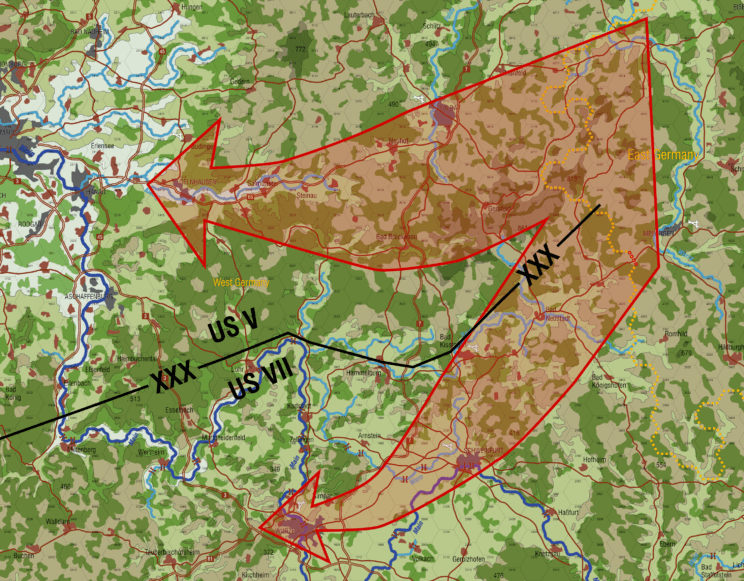

One of the most likely and dangerous Warsaw Pact offensive axes in this sector would have actually originated further north, in the area of the US V Corps. After the NATO covering forces had been forced to retreat and a corridor through Bad Neustadt and Bad Kissingen had been secured, a follow-up army could have exploited this breach to launch an offensive toward Schweinfurt and Würzburg, defended by an understrength West German 12. Panzer division and one US brigade.

Moreover, this offensive axis would have moved, at least in its initial phase, along the boundary line between the two US corps, always a good idea as boundaries are often a weak point in the enemy defense.

The capture of Würzburg, a vital road junction, would have opened the door to further advances in three possible directions, each posing a significant threat to NATO’s entire defensive posture in southern Germany.

The Duelists

Vive la France, on a Budget

The French army is of course one of the biggest novelties in this module. In 1985, France fielded very significant armed forces, and was probably second only to United States and West Germany in terms of possible contribution to the defense of the Central Front in a conflict against the Warsaw Pact. However, French army’s budget was limited by the need to maintain a very costly independent strategic nuclear component, as well as a very significant navy, with two carrier groups at its core.

Although France was a member of the alliance, its forces were not part of NATO’s integrated military structure and would have remained under French command during a conflict, leading to the limitations outlined in the ‘French Separate Command’ rule. However, this independent approach should not be mistaken for a lack of commitment to supporting its NATO allies. There was no doubt whatsoever that the French army would have intervened if Warsaw Pact had invaded West Germany.

French I Corps, consisting of two armoured and two light armoured divisions, would likely have been deployed in the Munich sector. French II Corps, with two armoured and one mechanised infantry division, could have reinforced the Nuremberg sector covered by this module. The newly formed French III Corps, also composed of two armoured and one mechanised infantry division, would have likely been placed under NORTHAG command, serving as a strategic reserve alongside the US III Corps after its arrival as part of OPERATION REFORGER.

A significant part of the Force d’Action Rapide (FAR, Rapid Deployment Force), five divisions strong, would have been probably committed too. This was one of the most discussed topics during development and is covered in detail in a separate chapter.

A unique aspect of the French army, unlike any other NATO force, was that it was structured, equipped, and trained mostly as a counterattack force. It was not designed for sustained conventional warfare. In 1985, the French army’s stated objective was to conduct short, high-intensity counterattacks against any enemy penetration, forcing the Soviets to face ‘the option of halting the offensive or crossing the nuclear threshold’.

Within this doctrine, France also considered the use of tactical nuclear weapons as a viable option, without necessarily triggering a full-scale nuclear exchange, provided its strategic nuclear deterrent remained intact. To this end, each French Corps had its own tactical nuclear forces, composed by two Pluton SSM battalions equipped with 25 kt warheads. Frankly, quite a gamble in my opinion.

Last but not least, the French army was definitely weak in the area of offensive electronic warfare, that is the capability to disrupt or jam the enemy communications. Probably no more than a couple of specifically equipped and trained companies were available in the whole French army.

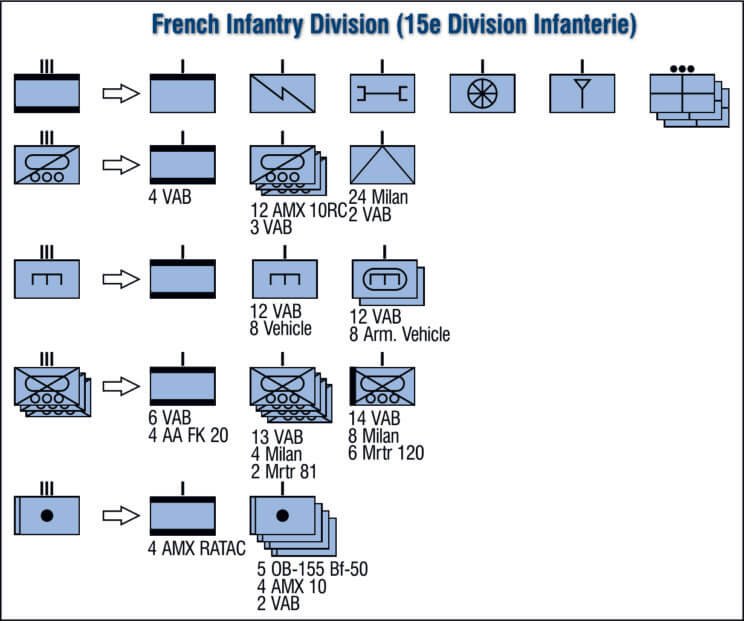

The French Divisions

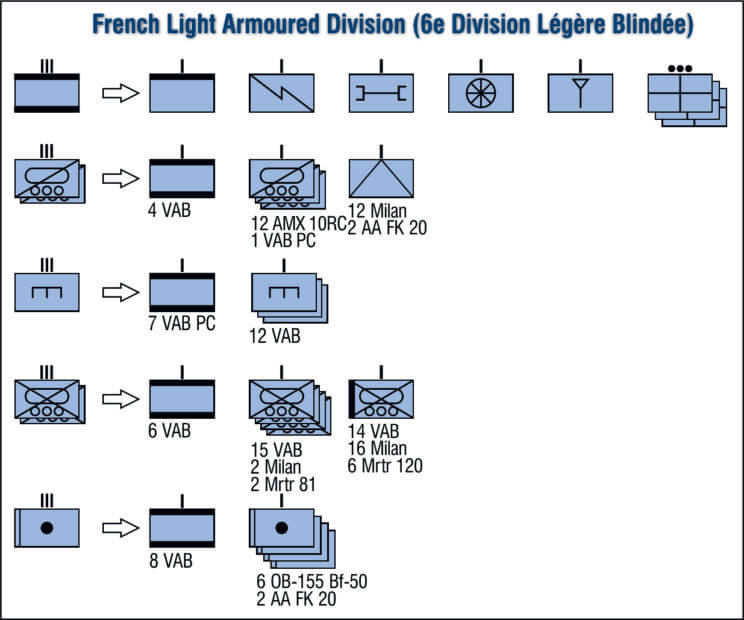

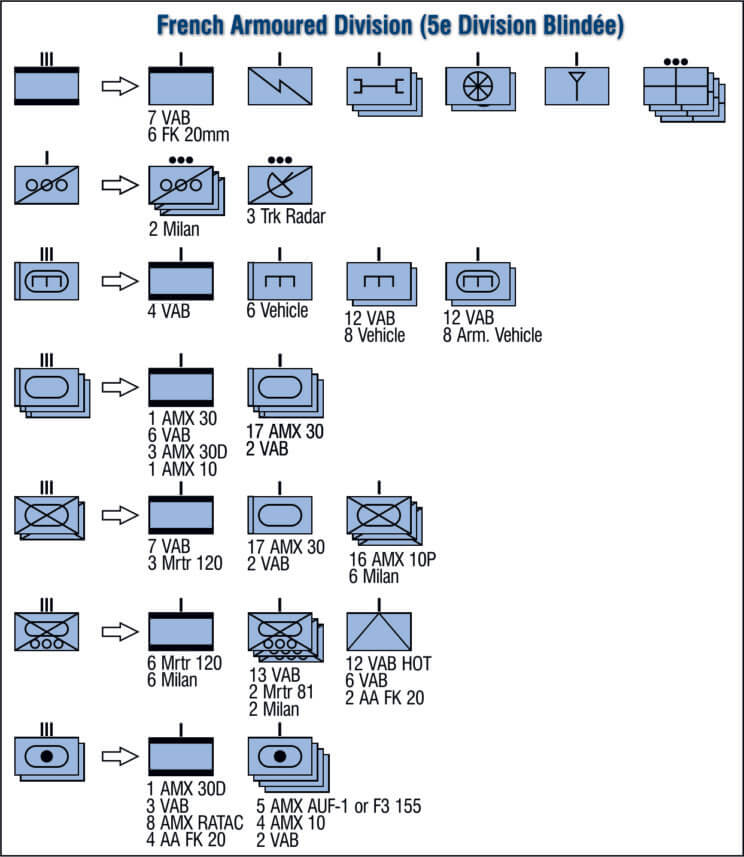

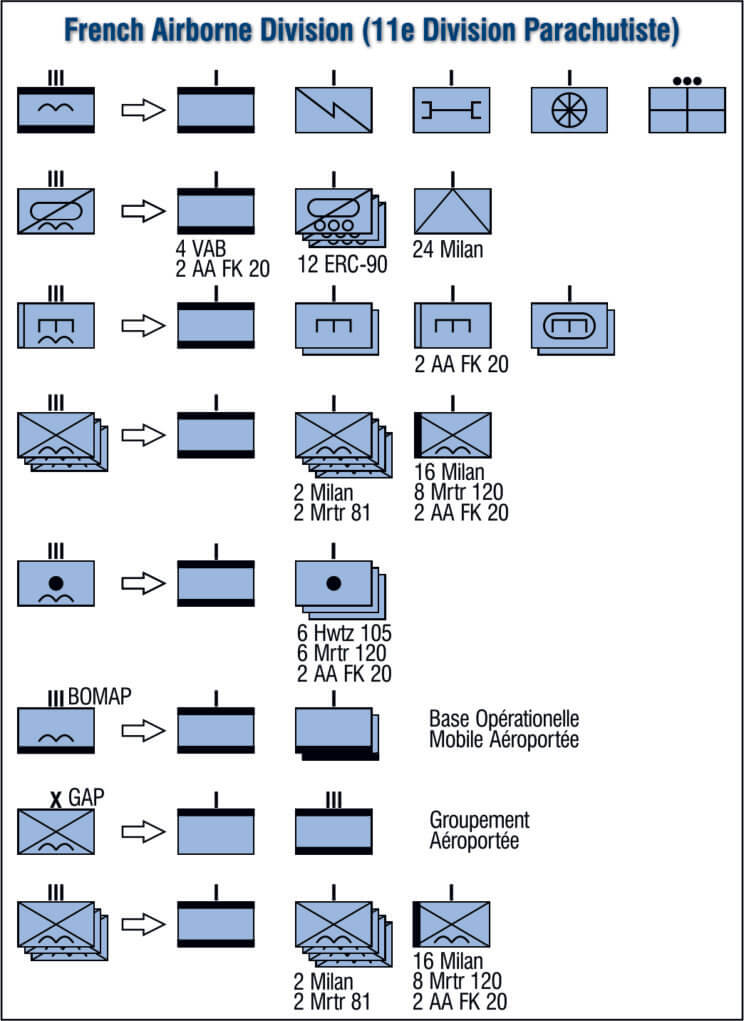

Following the reforms of 1977 and 1983, French divisions were organised as large brigades, with most of the logistic components at Corps level. The only exception to this was the 11e Division Parachutiste, that partially maintained a brigade-level structure due to its size and its possible employments within the FAR (Force d’Action Rapide).

As in the British and Canadian armies, the manoeuvre units within a division were nominally regiments, actually battalion-sized units. A division typically had four to six combat battalions, supported by one or two artillery battalions. The exact composition of each division could vary, both in the number of battalions within the division and the number of companies making up each battalion. Corps-level artillery could add an extra punch where needed.

The divisional artillery was generally modern, even though barely adequate as France was not deploying any heavy artillery as practically every other country on both sides. The largest calibre used by the army was the 155mm, considered sufficient for any purpose – similar to the often criticised “75mm only” doctrine in vigour in 1914.

Engineer support was good, with a strong and well-equipped engineers battalion assigned to each division.

The Force d’Action Rapide (FAR)

As an ex-colonial power maintaining strong ties with most of its former colonies, France has always been very active in the world. Political and military support has been continually provided to several countries in North and Central Africa, Near and Middle East, and more. The number of military interventions that took place since the end of World War Two is second only to the United States.

The well-known Foreign Legion had always been the first choice for these kind of operations, but in 1983, a more specific and flexible formation was created – the Force d’Action Rapide, consisting of the following:

- 6e Division Légère Blindée: The armoured element, particularly suited for low intensity operations in an hostile environment.

- 9e Division Infanterie de Marine: The marines element for overseas operations.

- 11e Division Parachutiste: The airborne element, deployed by airdrop or airlift using its assigned C160 Transall transport aircraft.

- 27e Division Infanterie Alpine: The mountain troops, suited for intervention in rugged terrain areas.

- 4e Division Aéromobile: The airmobile element, with three attack helicopters regiments, one transport helicopter regiment, and one small reconnaissance battalion.

There was a hot debate in the development team about if, when, and how, the FAR would have been used in a high-intensity conflict in central Europe.

The first point discussed was about the overall possibility of a FAR commitment in West Germany. Several military analysts at the time argued that the FAR’s lighter, more mobile equipment, such as wheeled vehicles like the AMX-10 RC, might struggle in a high-intensity conflict against heavily armoured Soviet forces. The FAR was perceived by some as optimised for power projection in post-colonial interventions or rapid flanking manoeuvres, rather than as a key player in NATO’s Central Front defense. Nevertheless, French officials insisted that the FAR was capable of contributing to NATO’s defense in the event of a Warsaw Pact invasion, particularly in scenarios where flexibility and rapid response were crucial.

The second point was about which FAR units would have been actually committed, if any. Military and logistic considerations pushed towards a deployment of the FAR as a whole; Political consideration suggested that it could have been split, leaving a couple of divisions as strategic reserve for possible overseas interventions within the French sphere of influence, where local potentates would have perceived the ongoing conflict in Europe as a perfect time to expand their ambitions. Think for example about Qaddafi in Chad, or the Somalian warlords in Djibouti.

On this second point, a look at the past could lead to different conclusions. In 1914, France almost immediately planned to recall most of its metropolitan troops stationed oversea; On the contrary, in 1940 France kept consistent metropolitan forces in its colonies, recalling them only when it was too late, and also sent an expeditionary force of three divisions to Norway only a few days before the disaster stroke.

So, how important was it for France in 1985 to protect its overseas sphere of influence, even during a NATO – Warsaw Pact conflict?

In the end, it was decided that a significant part of the FAR would have been deployed to West Germany: 6th Light Armoured, 11th Airborne, and 4th Airmobile divisions. The two remaining divisions, 9th Marines and 27th Alpine, would have stayed in France for a possible deployment to an overseas area of crisis.

A few extra words should be expended about a couple of FAR’s divisions.

The 4e Division Aeromobile was similar to the “High Technology Motorised Division” concept, fielded by the US 9th Infantry Division and abandoned after several attempts to fix it: A formation with a strong helicopter component, both attack and transport, and a light, highly mobile ground component. The primary tasks for the division were to provide fire support, air transport, and recon intelligence to the rest of the FAR.

The 11e Division Parachutiste was the biggest and only “true” division in the French army, amounting approximately at 14,000 men and with a subordinated brigade formation named Groupement Aèroportè (Airborne Group). As the 60 available C160 Transall could airlift a maximum of two battalions, this Airborne Group would have probably been the first wave airlifted to a friendly airbase in West Germany, followed by the rest of the division at a nine hours interval. Once the airlift to the area of operations had been completed, the division or part of it could have been employed as real paratroopers, or as airmobile troops transported by the 4th Airmobile division helicopters.

The French Equipment

The weapon systems and equipment fielded by the French army are probably less widely known than their American or German counterparts. Let’s see some of them in detail.

The AMX 30 was the Main Battle Tank fielded by most French armoured units. Its first prototype dated back to 1960, and followed the same philosophy adopted by Germany at the time: Quoting Jane’s Armour and Artillery 1985, the goal was to have a tank “which would be well armed, lighter, and more mobile than the tanks in service”. From this concept, the Germans developed the Leopard 1, and the French the AMX 30, both armed with a 105mm gun. Starting from 1982 an improved AMX 30B2 version was being produced, with integrated fire control, an LLLTV system (Low Light Level TV), and more. All considered a good MBT, with a barely sufficient armour protection and a lack of stabilisation as its weaknesses.

The AMX 10, primarily used in the armoured divisions, fielded a plethora of variants for almost every imaginable use: Infantry Fighting Vehicle (AMX 10P), Command Vehicle (AMX 10PC), Radar (AMX 10RATAC), Anti-Tank (AMX 10HOT), Recon (AMX 10RC, not tracked but wheeled), and a lot more. In its IFV version, the AMX 10P sports a 20mm gun, and can carry up to eight infantrymen, plus a crew of three.

The AMX 10RC (for “roues-canon” – wheels / cannon) and ERC 90 were conceptually similar vehicles, a seriously improved version of the AML 90 which had been the workhorse of the French army in the 1960’s and 1970’s, and embodied the French focus on firepower and mobility at the expense of protection. These were light armoured cars, sporting, respectively, a 105mm medium pressure gun with a laser range finder and an integrated fire control system, and a high-performance 90 mm gun with a laser range-finder.

The VAB (Véhicule de l’Avant Blindé) became the standard Armoured Personnel Carrier for infantry regiments in most French divisions. In its APC configuration, it was usually armed with a 7.62 mm machine gun, operated by a crew of two, with a transport capacity of up to ten fully equipped infantrymen. Despite being wheeled rather than tracked, which initially sparked debate over whether these regiments should be classified as mechanised or motorised, its excellent all-terrain performance ultimately led us to categorise them as mechanised infantry.

As for the artillery, the AUF-1 Self Propelled 155mm Gun was realised by mounting a 155mm GCT rapid fire howitzer on a AMX 30 chassis, and adding a armoured turret. This very effective system was only available in limited numbers in 1985. The F3 Self Propelled 155mm Gun used an older AMX 13 chassis and a 155mm howitzer, resulting in the lightest 155mm motorised artillery ever produced.

French infantry was also quite well equipped in antitank weapons, ranging from 58mm dual-purpose rifle grenades to the ubiquitous Milan ATGM, with the 89mm LRAC replacing the Carl Gustav and the new 112mm APILAS disposable rocket launcher making its debut.

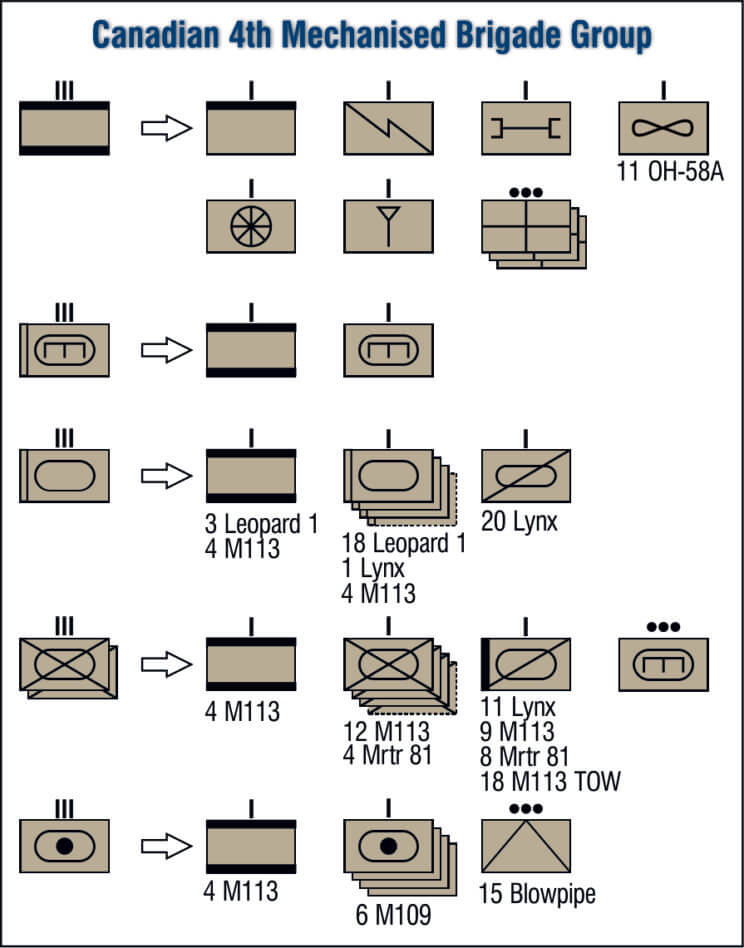

The Canadians, Not That Polite After All

The 4th Canadian Mechanised Brigade Group (4CMBG) was the only Canadian formation stationed in West Germany, based in the distant German village of Lahr, near the border with France.

Initially a frontline unit within the NORTHAG/BAOR defensive structure, the Canadian brigade’s role shifted after significant defense budget cuts implemented by Pierre Trudeau’s government in 1970. As a result, NATO reassessed its role and redeployed it to southern Germany, designating it as an operational reserve for the US VII Corps or the West German II Corps.

In the early 1980s, with Canada’s decision to increase military spending, the brigade began to regain its former strength and prominence. By 1985, it was once again a top quality force with the following composition (It’s important to note that in Canadian terminology too, a “regiment” was essentially the equivalent of a battalion):

- One armour regiment fielding three tank companies and one recon company, for a total of 57 Leopard 1, 16 M113 and 20 Lynx

- Two mechanised regiments with three infantry companies each, totalling 36 M113 and 12 Mortars, plus a support company with 9 M113, 8 M125 with 81mm Mortar, 18 M113 TOW, and 11 Lynx.

- One self-propelled artillery regiment with 24 M109.

- One Engineer regiment.

- One Tactical Helicopters company, with 11 OH-58A.

Additionally, personnel of a fourth company in the combat regiments would have been airlifted and married with pre-positioned equipment in West Germany. How quickly this would have happened is anybody’s guess, but given the initial reserve status of the brigade we considered this fourth company augmentation as already completed.

The Strange Case of the 12th Panzer Division

The West German 12th Panzer Division had a unique and somewhat complex position within CENTAG. While nominally subordinate to the West German III Corps, it was assigned to defend the Würzburg sector under the operational control of the US VII Corps. Further complicating this arrangement, the division’s 34th Panzer Brigade was detached and held further north, as operational reserve for the West German III Corps. To compensate for this loss, the US 1st Armored Division (Forward) brigade was placed under the operational control of the 12th Panzer Division.

This intricate structure introduced a variety of challenges, ranging from communication difficulties to differences in doctrine and fire support coordination. To mitigate these issues, a specialised NATO Division Support Platoon (GE/US) was created using personnel from both nations and custom communication systems. How effective this solution would have been in the heat of war remains uncertain.

Back to us and the C3 system, the inherent difficulties of such a structure would have likely made it hard for the West German units under US command to fully implement the German Auftragstaktik (Mission-type tactics). Although some efforts were made to instil this decentralised, flexible command approach, by 1985 the US Army had not yet fully absorbed it. Hence, the limitations on its use by WG 12. Panzerdivision while under US command.

Please also note that additional counters having the WG 12Pz Division subordinate to WG III Corps are provided, along with the units for the 34th Panzer Brigade. These give NATO the flexibility to explore alternative strategies when using multiple C3 modules.

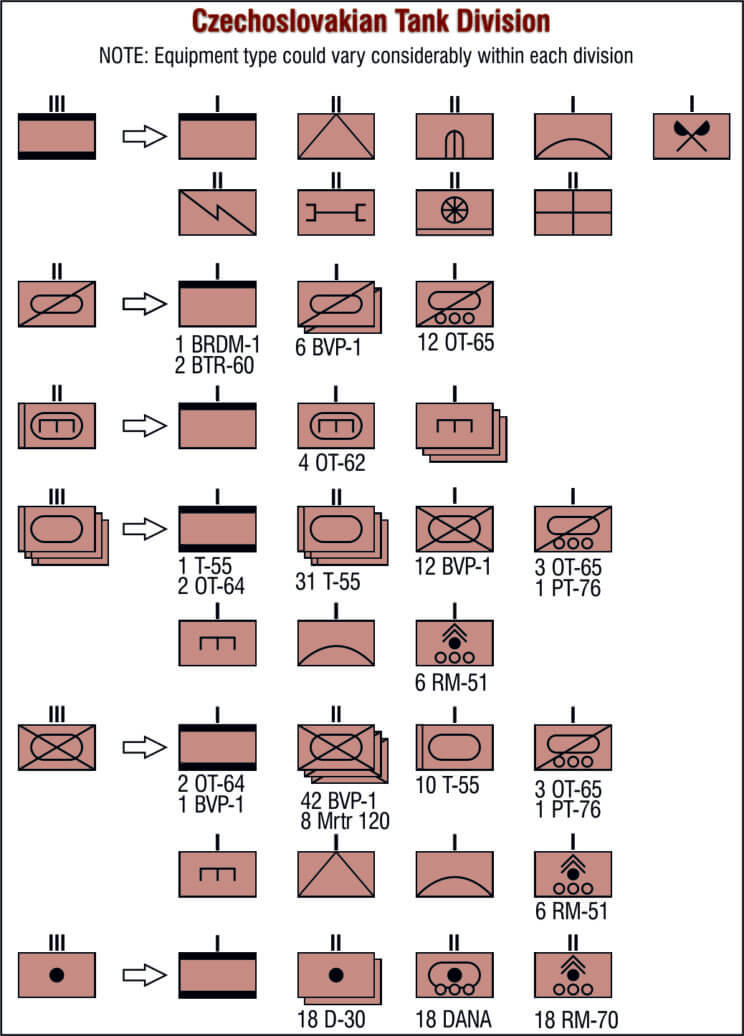

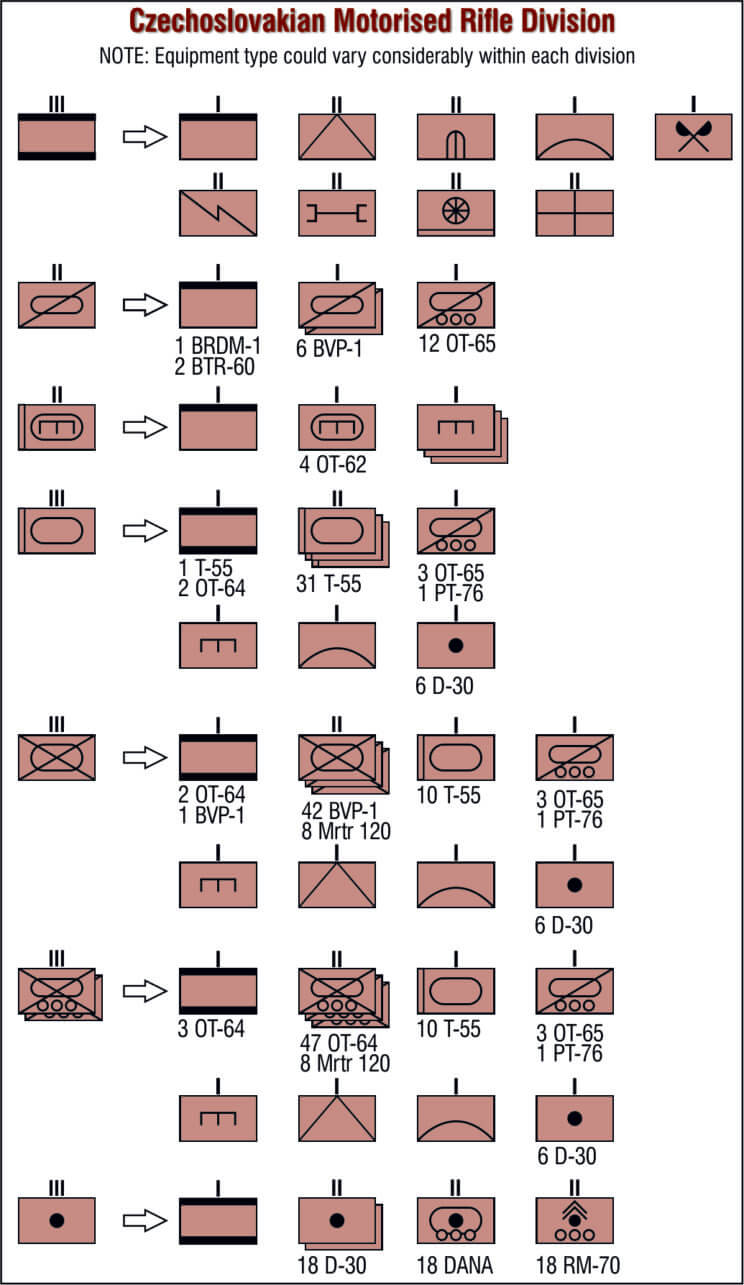

Czechoslovakia, a Taste in Beer and Guns

The Czechoslovakian contribution to the liberation of Western Europe could have consisted of two armies:

- The 1st Army, fielding one tank and three motorised rifle divisions. These divisions were permanently manned at 75% strength and classified as Category I in the US evaluation system, meaning they could have been fully operational within 48 hours in the event of conflict.

- The 4th Army, with two tank and two motorised rifle divisions. These divisions had a lower level of readiness (Category II or Category III) and would have required several days to become fully manned and ready for deployment.

The internal situation in Czechoslovakia must also be considered. In 1985, only 18 years had passed since the Prague Spring and the subsequent invasion by the brotherly comrades of the Warsaw Pact. It is difficult to imagine the Czechs as firm supporters of a war against NATO. Therefore, in our strategic scenario, two divisions from the 4th Army remain in Czechoslovakia, along with additional Soviet troops, to ensure strict adherence to the Socialist Doctrine.

The quality of the divisions was generally near the standard Warsaw Pact level, with a few highs and several lows.

Tank regiments were mostly equipped with T-54 or T-55 tanks, while motorised rifle regiments fielded the BVP-1, a locally produced version of the Soviet BMP-1, and the OT-64 SKOT, a capable wheeled APC jointly produced by Czechoslovakia and Poland.

It is also important to note that Czechoslovakian motorised rifle divisions did not include a separate tank battalion, unlike their Soviet counterparts, and the tank regiments had only one motorised rifle company instead of a battalion.

Artillery at the regimental level was typically weaker than that of the Soviets, usually consisting of a single battery equipped with D-30 122mm towed howitzers or RM-51 rocket launchers, the Czechoslovakian version of the venerable Soviet BM-13 Katyusha.

Things improved at the divisional level, with each division fielding two battalions of D-30 122mm towed howitzers, one battalion of SpGH DANA 152mm self-propelled howitzers, and, in most cases, one battalion of RM-70 rocket launchers. Both the DANA and the RM-70 were excellent locally produced weapon systems.

Each army also had a substantial artillery force to support its divisions: one 9K72 (Scud) SSM Heavy Artillery Brigade, and one Cannon Artillery Brigade fielding a mix of M-46 130mm towed howitzers, wz. 18/46 152mm howitzers, and SpGH DANA 152mm self-propelled howitzers.

Bibliography

As usual, this is only a partial bibliography, as an unaccountable number of internet sites have been used during the research.

Generic

James F. Dunnigan, Stephen B. Patrick (1980): NATO Division Commander

International Institute for Strategic Studies (1985): The Military Balance 1984 – 1985

Various Authors (1986): Jane’s Armour and Artillery 1985-86

Michael Napier (2020): In Cold War Skies – NATO and Soviet Air Power 1949 – 1989

U.S. Combined Arms Operations Research (1983): Deep Attack Map Exercise (DAME) Rules and Operating Procedures

U.S. Army (1994): FM 34-130 Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield

U.S. Army (1992): FM 90-13 River Crossing Operations

U.S. Army (1982): FM 100-5 Operations

U.S. Army (1986): FM 3-6 Field Behavior of NBC Agents

David Miller (2012): The Cold War – A Military History

Neil Munro (1991): The Quick and the Dead – Electronic Combat in Modern Warfare

NATO

David C. Isby (1985): Armies of NATO’s Central Front

Various Authors (2012): Die Bundeswehr 1989, Teil 2.1

Various Authors (2012): Die Bundeswehr 1989, Teil 2.2

Maurice Faivre (2019): Les Armées dans la Guerre Froide en Centre–Europe: Forces, renseignement, plans d’opérations

Paul-Werner Krapke (Date unknown): Leopard 2 – sein Werden und seine Leistung

Bundeswehr (Unpublished): 12. PzDiv Order of Battle, French Orders of Battle

Bundeswehr (Unpublished): General Defense Plan 82 (maps and extracts)

US Army Armor School (1981): US Army Armor Reference Data

Helmut R. Hammerich (2011): Southern Germany as a Cornerstone of Europe’s Defense

Warsaw Pact

Michael Holm (2015): Soviet Armed Forces 1945 – 1991 http://www.ww2.dk/new/newindex.htm

V.I. Feskov, K.A. Kalashnikov, V.I. Golikov (2004): The Soviet Army in the Years of the Cold War 1945–91

Foreign Broadcast Information Service (1987): East Europe Report

Central Intelligence Agency (1980): Warsaw Pact Forces in Czechoslovakia

Central Intelligence Agency (1988): USSR Staff Academy Lesson: Rocket Troops and Artillery in a Front Offensive Operation

David M Glantz (1991): Soviet Military Operational Art – In Pursuit of Deep Battle

David C. Isby (1985): Weapons and Tactics of the Soviet Army

U.S. Army (1991): Army Field Manual, Vol. II Part 2 – Soviet Doctrine, A Treatise on Soviet Operational Art

U.S. Army (1984): FM 100-2-1 The Soviet Army – Operations and Tactics

U.S. Army (1984): FM 100-2-2 Soviet Specialized Warfare and Rear Area Support

U.S. Army (1991): FM 100-2-3 The Soviet Army – Troops, Organization and Equipment

Thanks Kev for publishing this!

BTW, there’s a typo error in the “The Strange Case of 12th Panzer Division” chapter: the US brigade under WG 12. Panzer command was of course from the 1st Infantry Division and not the 1st Armored Division.

The horrors of copy and paste in a hurry

From 1972-74 I was stationed at a tactical nuclear warhead storage and maintenance facility about 300 or so clicks from the Czech border. The idea was that the Germans had the launchers and we would supply them the warheads when giving the word. We had no doubt that a war with the Warsaw Pact would begin with our facility being taken out. We had heated discussions about whether it would be by Spetsnaz Commandoes, by tactical nuke (my choice) or by ballistic missile attack.

If they were not stored in an underground bunker, my money would go on a SSM attack – It fits perfectly with the Soviet doctrine.

If underground, they would have needed a quite big Spetsnaz sleeper cell, as an insertion 300 km behind the front line had in my opinion zero chances.

Thanks for catching the error Fabrizio. since I was in that brigade at the time, it is sort of important to me.

Great article, I thoroughly enjoyed the read. This is such a great re-boot of the classic 5th Corps game system. I played that to death back in the early 80’s.

Thanks for sharing.

Dear Comerades, greetings from Paris !

Very interesting to see the french forces coming in the fray, recalling me the good old days of FAR 90 Casus Belli vintage from Laurent Henninger. A great classic we all played… (I have many copies so feel free to ask me.)

Concerning the rather strange US/WG 12Pz coordination problem I recall to have participated in 1993 to the Montcornet Manoeuvre with the Brigade Franco-Allemande (BFA) as a circulation agent from the command & support regiment of 10 th Armored Division (10 RCS). I remember a glorious charge as the blue force traffic control agent, standing up in my P4 holding my ANF-1 7.62 mm MG, well, spotting red force AMX10-P’s all along on both sides of the road. I have always felt a bit skeptical about the success of this 30 km charge, but well it was a good ride in the Ardennes…

Well just to contribute to the community about the liberating forces, let me share this fantastic blog :

https://thesovietarmourblog.blogspot.com/

Dear Comerades, greetings from Paris !

Very interesting to see the french forces coming in the fray, recalling me the good old days of FAR 90 Casus Belli vintage from Laurent Henninger. A great classic we all played… (I have many copies so feel free to ask me.)

Concerning the rather strange US/WG 12Pz coordination problem I recall to have participated in 1993 to the Montcornet Manoeuvre with the Brigade Franco-Allemande (BFA) as a circulation agent from the command & support regiment of 10 th Armored Division (10 RCS). I remember a glorious charge as the blue force traffic control agent, standing up in my Peugeot P4 patrol car holding my ANF-1 7.62 mm MG, well, spotting red force AMX10-P’s all along on both sides of the road. I have always felt a bit skeptical about the success of this 30 km charge, but well it was a good ride in the Ardennes…

Well just to contribute to the community about the liberating forces, let me share this fantastic blog :

https://thesovietarmourblog.blogspot.com/

All the best comerades !!! Continue the great job !

Comerade Frankivitch.