GMT Games partner and game developer Mark Simonitch has done it again.

After releasing now the sixth game using the ZOC bond system [was France 1940 one as well, I have not played so I can’t say definitively, unless I go quickly read the rules! ] So, let’s call it six plus an expansion for Stalingrad 42. Nice, oh and one on the way with Africa ’41 on P500 though my understanding is this may not use ZOC bonds for lots of very good reasons in that very dynamic theatre of war.

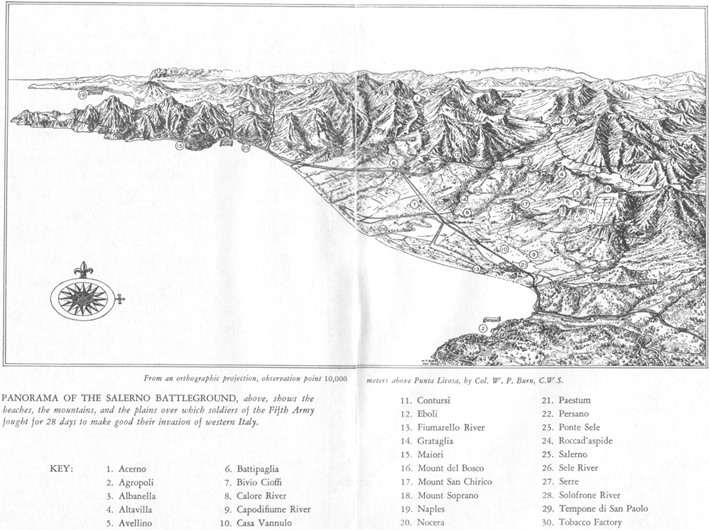

This time Mark explores the landings around Salerno. This battle and the landings have of course been covered before but perhaps not as succinctly and cleanly as this module presents.

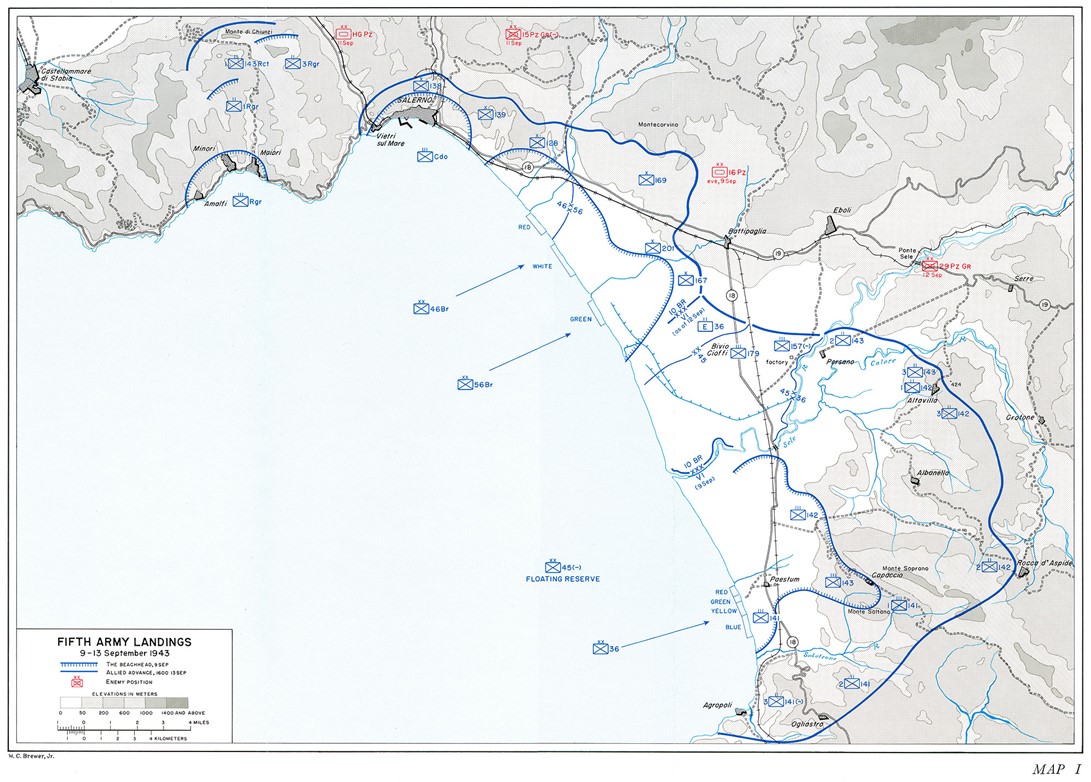

Scale clocks in timewise as daily turns one of the most granular for this system and the same as Normandy ’44. So too we see units as small as battalions at play as well. Terrain is measured in 3.8km hexes. A major difference for players will be the challenging terrain around the Bay of Salerno:

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Note I have 3 videos online that provide a ‘reading’ from Rick Atkinsons coverage of the landings.

First one is here:

The Landings:

Some back channel efforts had secured the agreement between the Allies and Italy that they would surrender. As soon as it had been made clear that the Italian fleet was going to surrender as called for in the agreement between the Italian government and the Allies, Admiral Cunningham had released the 12th Cruiser Squadron to pick up the British 1st Airborne Division for the attack on the naval base at Taranto, called “Operation Slapstick.” The paratroopers were embarked, and on September 8, as the Allied forces moved in on Salerno, the paratroopers were at sea. They arrived on the following day, and landed unopposed. There was one casualty: the minelayer Abidel, loaded with paratroopers, hit a mine while anchoring. She exploded, with heavy loss of life.

As the Allied convoys approached Salerno on the night of September 8, the sea was calm and the night was clear. The American and British troops suffered none of the usual tension the night before an invasion. It would be, as the cockneys liked to say, “a piece of cake.” The announcement of the Italian surrender was in the air, and anyone who had been in Sicily could only too easily recall the sensation of being greeted as conquering heroes by the people of Sicily. The troops were arriving in an almost festive air.

The minesweepers came in and did their job without arousing the troops on shore. The invasion fleets assembled in the landing areas. The ships of the fleets performed with much more precision than they had in the Sicily landings, the result of experience.

But there the dream ended. In the northern sector, the British were detected before they could get started into the landing craft. The shore batteries, manned by Germans who had just taken over from the Italians, opened fire with great accuracy on the ships carrying the Rangers and the Commandos. Five minutes after they landed, the destroyers in the British assault area opened an intensive 15-minute barrage of gun and rocket fire to support the landings. Fortunately, the commanders in the north had made contingency arrangements for full fire support. The British warships fired back on each coastal battery, and the supporting destroyers moved in behind the assault waves to give close-fire support. The Rangers and Commandos landed against light opposition and secured their objectives, with few accidents. One landing craft did land on the wrong beach, creating some confusion.

The troops on shore did not just walk in. The Commandos suffered some casualties but managed to hold their positions. The British 46th Infantry Division was fortunate to land away from any German strong points, but the 56th Infantry Division ran into heavy opposition. By the end of the day, the dream of an easy time had ended. Neither division had achieved its objectives and the 56th had suffered heavy losses. The port of Salerno was not far, but the 46th had not captured it. The 56th reached the edge of Montecorvino airfield but could not go any farther.

In the American sector, there was surprise; they received a hot welcome, not just a warm one. The beaches were silent as the landing craft went in, but when the men hit the beach, they were met by heavy fire from concealed positions. Much of the fire was too high to do much harm, but it soon steadied down and the losses began. After landing safely, on the extreme right, the 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry Division began to work its way to the railroad station near the Solofrone River. But the third wave of boats met German fire so intense that it and the following waves were immobilized on the beach. The fact that no plan for fire support from the ships had been arranged was almost the undoing of the landing. The 3rd Battalion on Yellow Beach ran into German fire from the beginning, 400 yards from the shore.

Following are the words of the official U. S. Army historian describing the scene:

From the massive heights that loomed over all the beaches, and from Monta Sopprano in particular, came the flashes and sounds of the enemy fire. Flares of all colours illuminated the sky, while the crisscrossing tracers of machine guns flashed over the beaches, the heaviest concentrations coming from the right near Agropoli. Some boat pilots who judged the fire too strong for them to land their troops turned around and headed back toward the ships, until intercepted by control vessels and sent again to shore.

Landing craft foundered and some burned near the shore or drifted in the waves. Lost equipment floated on the surface and communications equipment was lost. Boats sank and men swam for the beach. As one mortar squad debarked, the gunner tripped on the ramp and dropped the mortar into the water. Machine-gun fire scattered that platoon, and the men who hit the shore joined whatever unit they were near. Some mortars came ashore without any ammunition. The Americans were finding this a much tougher landing than anything they had ever experienced before.

Casualties were very heavy but the 36th Infantry Division, a National Guard Unit, had been well trained and managed to win most of its D- Day objectives. By dusk, it was holding a narrow beachhead around the Roman ruins of Paestum.

The British and the Americans had met the German 16th Panzer Division, which had 17,000 men, 100 tanks, and 36 assault guns. At the end of the first day, it was apparent that the invasion was already in trouble. The Italians had been counted on for support by the Allies but had produced none. The Germans were very strong and could now concentrate all the weight of their Tenth Army against the U. S. Fifth Army before the British Eighth Army could come up from the south. The Americans still did not know it, but they were facing a numerically superior force, and one very skilled in the art of war.

Now one of the problems over which General Eisenhower had glissaded so easily arose to haunt the Allies: the serious shortage of shipping. The beachheads needed reinforcement immediately.

When dawn came on D plus one, the seriousness of the Allied position began to become apparent. They occupied two corners of the beach. Every action could be observed by the Germans on the hills around Salerno.

Shortly after dawn in the American sector, German tanks came into action working in small groups, supported by their infantry in platoon units. A lone tank reached the beach shortly after dawn and fired on the landing craft approaching. Antiaircraft guns on the LSTs and machine guns on the landing craft took the tank under fire and soon drove it off. Without any naval support fire, it was individual American infantrymen who kept the German tanks at bay in the south during these early hours. Corporal Roy C. Davis, a bazookaman, crawled under machine-gun bursts up the beach until he got to a point near a tank. With one round, he pierced the tank’s armor, then crept up to the disabled vehicle and thrust a grenade through the hole, killing the crew. Sergeant John Y. McGill jumped onto a tank and dropped a grenade through the open turret hatch. Even men without useful weapons helped. Private First Class Harry Harpel kept one group of tanks from reaching the beach by moving the loose planking of a bridge across an irrigation canal. These untried American troops moved with the efficiency of veterans.

But they were badly hampered by the lack of naval fire, and the American tanks, in particular, were disorganized and slow to get ashore. Many of the tanks did not get ashore until afternoon and some not until after nightfall. Six LSTs carrying tanks of the 191st Tank Battalion, moving toward Blue Beach at 6:30 in the morning, were hit by enemy shell fire; four received direct hits and one tank was burning. For five hours the LSTs circled aimlessly, and at 11:00 a. m. finally approached the shore. With neither artillery nor tanks in support during the first four hours, the infantry depended to a great extent on a few 40-mm antiaircraft guns that came ashore at daylight.

At the end of D Day, the Allied troops were ashore, with the British controlling the north entrance to the beaches; the Americans controlled the south. But the Germans controlled the center where Route 19 and Route 94 arrived at a gap in the hills and from which the Germans could bombard the beaches with their artillery and bring their tanks down when they wished.

So although the landings were an official success, they placed the troops in peril. Immediate reinforcement, which they could not get, was needed, as well as the speedy arrival of the Eighth Army from the south.

Almost from the beginning, General Alexander recognized the problem. He ordered the Eighth Army to race for Salerno even though Montgomery argued that to hurry was to take risks. Sometimes, said Alexander, even Montgomery had to take risks. Eighteen American LSTs, which had been assigned to other theaters, were still in African ports, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff ordered their release to build up the force at Salerno.

General von Vietinghoff now recognized his opportunity. If he could bring up reinforcements and destroy the Allied landings at Salerno, he could then turn his efforts against the Eighth Army in the south and destroy that force methodically. It was a race against time. The Germans had the advantage of proximity and numbers, and the use of rail and road transport to bring up their troops. Von Vietinghoff ordered General Herr, in the south, to break off contact with the Eighth Army and move the 76th Panzer Corps toward Salerno. The 26th Panzer Division and the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division were to leave only rear guard behind and move at its best speed over the 125 miles of mountain road to the beachhead. General Hube’s 14th Panzer Corps was ordered away from the Gulf of Gaeta to send the 15th Panzer Grenadier and the Hermann Goering Panzer Divisions south to block any advance of the Allies north to take Naples. Field Marshal Kesselring ordered General Student to release the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division from Rome and asked the OKW for Field Marshal Rommel’s two Panzer divisions, a request that was denied, but still five divisions could come to the aid of the German troops at Salerno. That meant von Vietinghoff could move enough troops to have six divisions to contest the four that General Clark had available. The Allies had air superiority, but it was not very strong.

On the morning of September 10, the Americans landed part of their floating reserve: the 45th Infantry Division. Clark visited the beachhead and was pleased with the conditions in the 6th Corps area. He visited General McCreery and learned what resistance the British were meeting in the north. McCreery indicated it would be difficult for the British to advance to the point where they were to rendezvous with 6th Corps. So, Clark ordered reinforcements to the 10th Corps area in view of the preponderance of German strength located there. Clark was very optimistic. He told General Alexander that he expected to be able to attack north toward Naples. So favorable did the situation seem that the Northwest African Tactical Air Force proposed to reduce the fighter cover over the beaches. Just at this point the Germans were planning to step up their air attacks.

On September 10 and 11, both sides did their best to build up their forces and contain the enemy. The German effort was directed first against the British 10th Corps, which threatened Naples. The Commandos, Rangers, and the 46th Infantry Division were hit by the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division and the Hermann Goering Panzer Division. The 46th managed to capture Salerno, but the Germans had the high ground and kept the harbor under observation and fire.

The confusion between commands continued. The forces off Salerno saw that the number of Allied air sorties was decreasing and protested to the air force, but the air force saw that the air opposition over the beaches was light on September 9 and, thus, cut back the number of fighter sorties as the Germans were increasing theirs. On September 10, the number of Allied fighters was definitely decreased, as more Germans came in. By the 11th, American Admiral Hewitt radioed Eisenhower that the status of the beachhead was growing critical because of the lack of air support. He was told that the only help that was coming was from Admiral Philip Vian, commander of the carrier force.

The Germans continued to hold the Montecorvino airfield and stopped the 56th Infantry Division, which was trying to get to Monte Eboli. Because of the concentration of the Germans on the British 10th Corps, the American 6th Corps was left alone to expand its bridgehead and secure key points overlooking the Ponte Sele bridge. However, that left a huge gap between the British and the American forces, so Clark landed his floating reserve to fill it.

Ashore once again on September 11 Clark was impressed by the way German pressure was building against the British area in the Battapaglia area, where they had pushed into the outskirts of Vietri and were within 12 miles of Salerno. On that day the Germans had captured 1,500 prisoners, most of them in the British sector. That night American troops were moved into the gap between the two forces.

By this time the air situation was indeed serious. The Germans launched 450 sorties by fighters and bombers and 100 sorties by heavy bombers in the first three days of the battle; and they sank four transports, one heavy cruiser, and seven landing craft and made many hits on the Allied fleet. On September 11, a near miss damaged the cruiser Philadelphia, another damaged a Dutch gunboat, and a direct hit on the cruiser Savannah put it out of action. Admiral Hewitt had to declare his situation critical to Admiral Cunningham, who sent the cruisers Aurora and Penelope from Malta.

Clark came ashore again on September 12 and found the British 46th Infantry Division badly bruised and the German strength increasing and pointing toward the center of the beachhead. He had evidence that the Germans were preparing to launch an attack in the near future, and his forces were spread very thin.

After four days, the Allied beachhead was still dangerously shallow and the number of troops to man the perimeter was very small. Clark decided that

day to bring his headquarters ashore, as a way to preserve and enhance troop morale.

Credit: https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2016/10/04/salerno-landings/

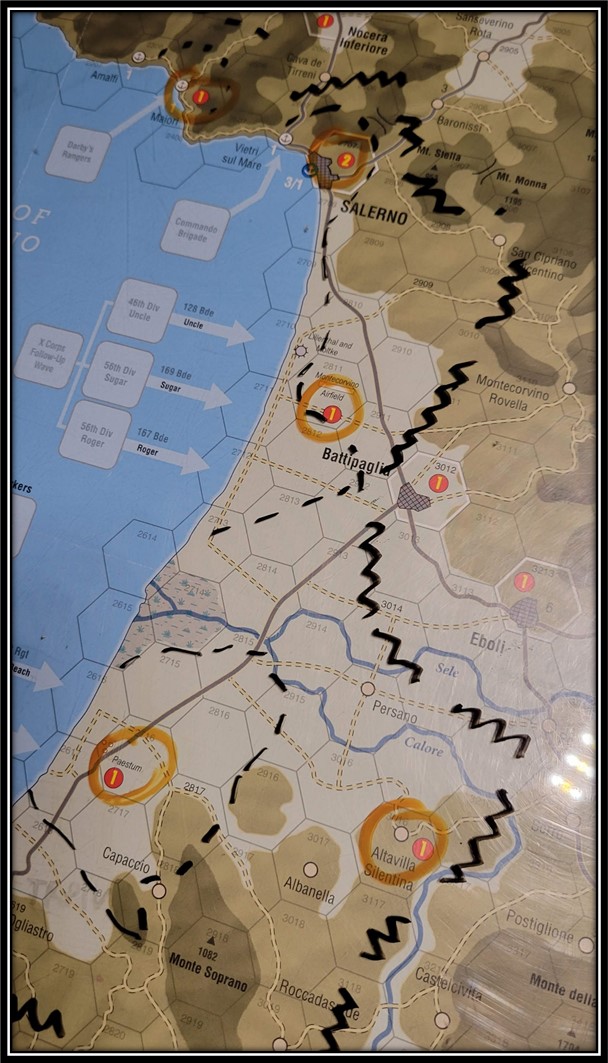

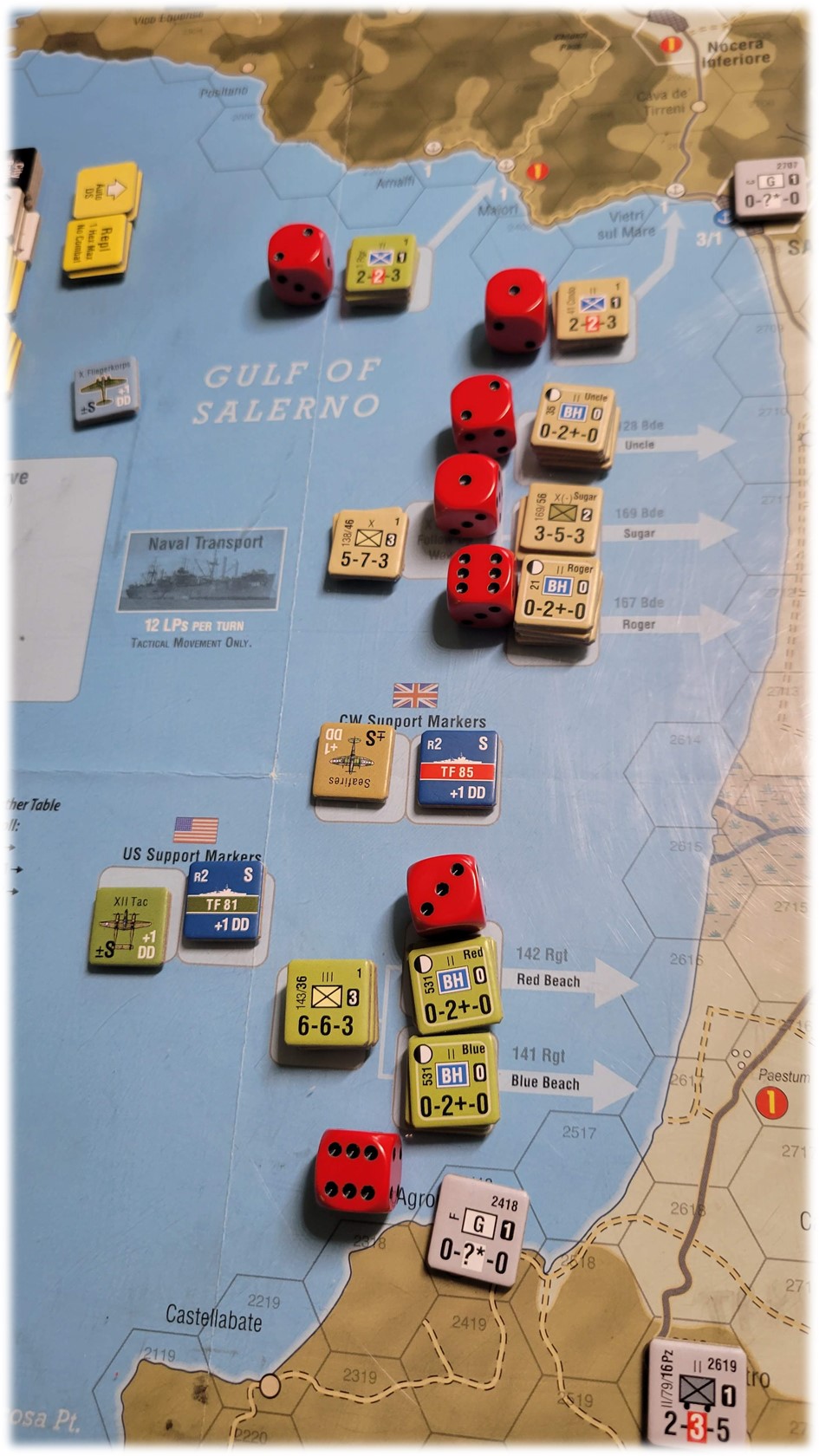

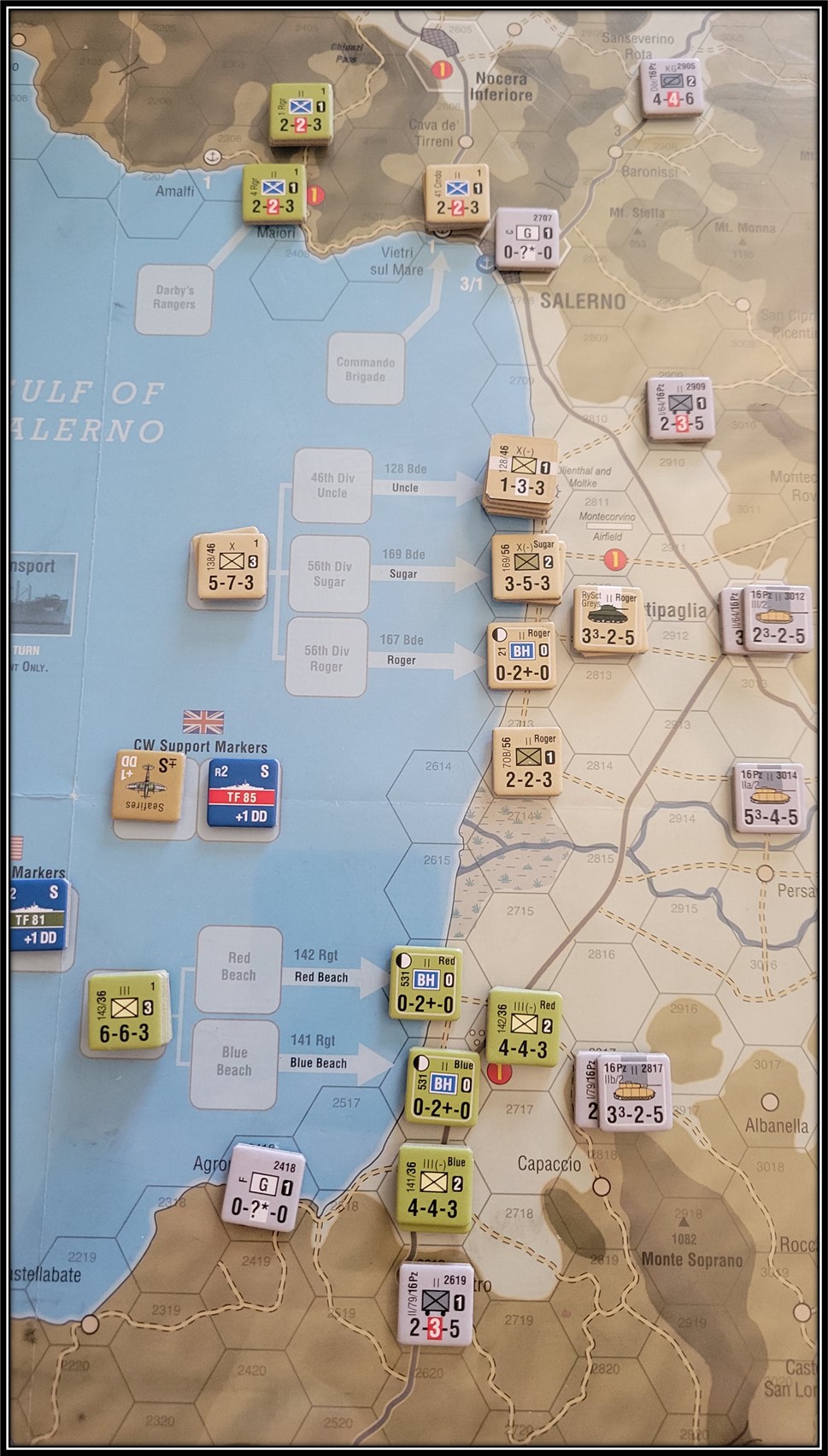

The squiggly lines above show the initial landing successes and VP locations captured on day one circled in orange.

VIDEO INSERTS Historical progress and readings.

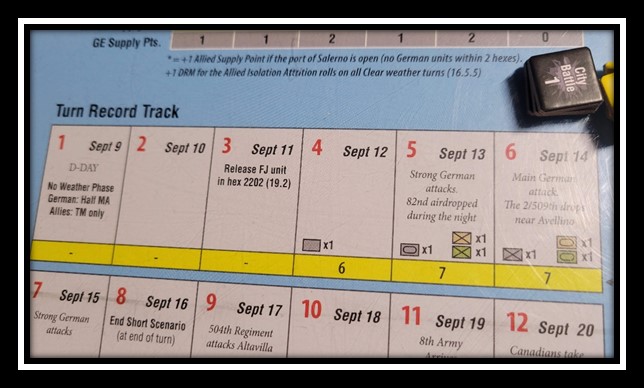

Thus by the 14th of September just seven short turns into the action the Allies are tasked with maintaining the Allied historical rate of success of seven VP hexes! Success landing will be critical as will using your forces effectively from the get go. On the opposing side the Germans have their hands full with four divisions landing and just the 16th Panzer Division plus ancillaries to hold the coastline.

The landings are model of simplicity reflecting the relatively unopposed effort. What matters most is how far will your landing forces progress once upon the shore. As you can see the UK and Darby’s boys did not fare well!

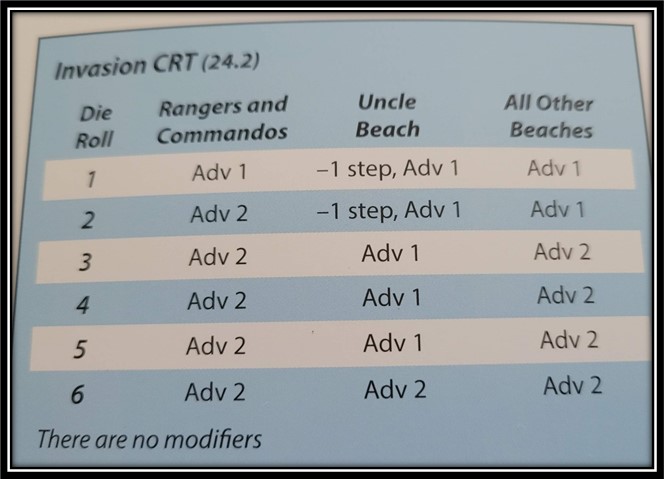

This is handled via a simple die roll on a table.

This means that the beaches can be hotly contested.

Next part of our report will highlight the combat and progress of the German reaction.

Onto game play from here.