“THIS RUINED THE CAUSE OF GREECE, AT A TIME WHEN SHE WAS STILL

ABLE IN SOME WAY OR OTHER TO RECOVER FROM HER GRIEVOUS PLIGHT

AND ESCAPE MACEDONIAN GREED AND INSOLENCE”

PLUTARCH AGIS AND

CLEOMENES 16.1

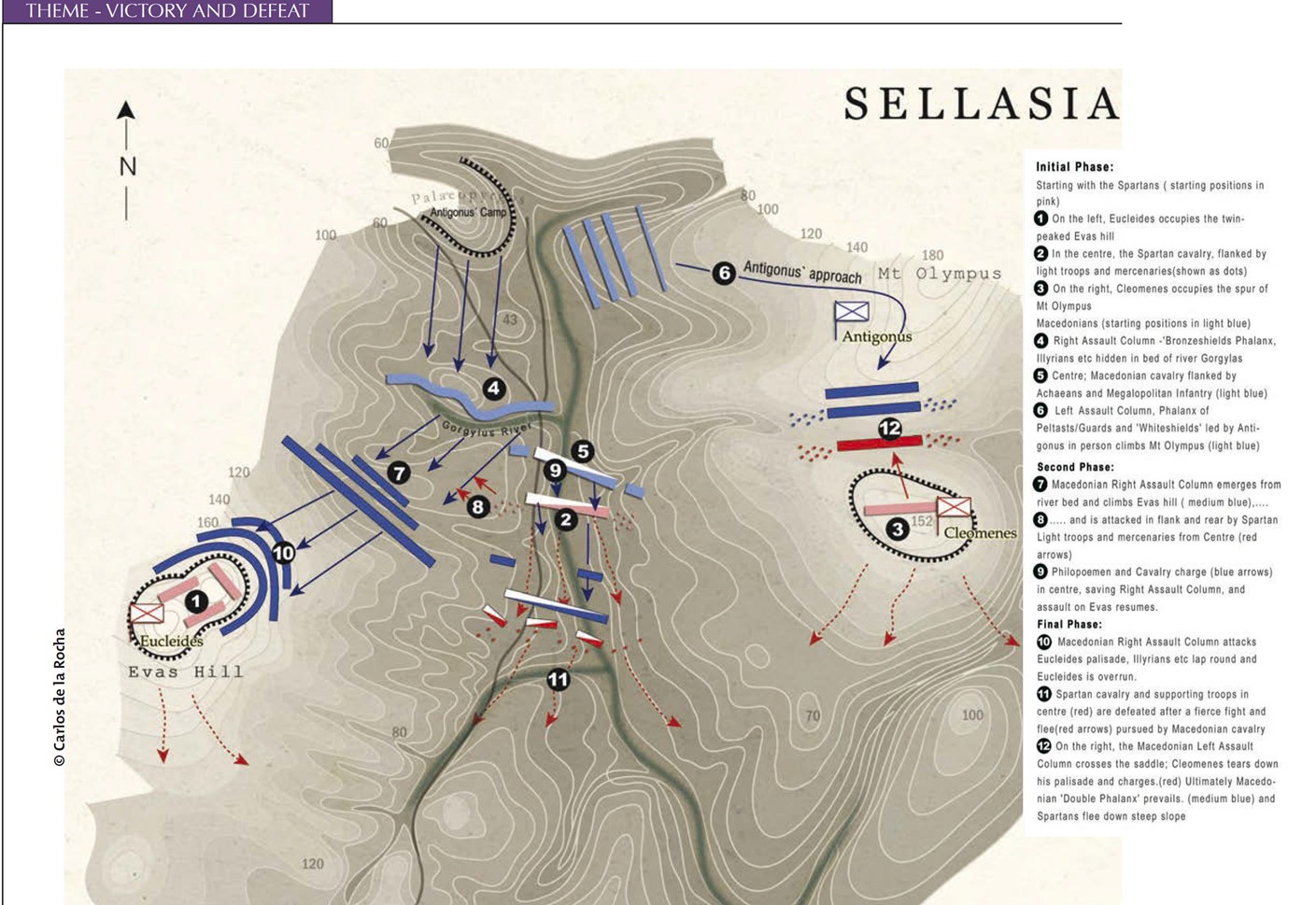

Cleomenean War

From Military-Wiki:

Greece at around the time of the Cleomenean War – image

Date 229/228[1]–222 BC

Location Peloponnese

Result Achaean and Macedonian victory

Territorial changes Acro corinth, Corinth, Heraea and Orchomenus to Macedon[2]

Belligerents: Sparta, Elis, Achaean League, Macedon

The Cleomenean War[3] (229/228–222 BC) was fought by Sparta and its ally, Elis, against the Achaean League and Macedon. The war ended in a Macedonian and Achaean victory.

While we all love Bergs witty comment and assessments, the combination of forces here, the sides and who was fighting and why triggered me to do some further reading.

It ends up Cleomenes’ really screwed the pooch here for the Spartan faction. The dual kingship had faltered, with murder and betrayal. Laconia was under threat from expanding tribes and this all meant one thing. War.

So of course outside forces tried to ply their hand in a typical Darian manner. With the Egyptians getting gold and support into the hands of both sides!

But I digress. Let me share what I found on the wiki and in the estimable Ancient Warfare Magazine Vol II.2. as a long preamble to this very interesting classical Phalanx v Phalanx battle in horrendous terrain in the shadow of My Olympus no less!

The Macedonian hegemony over the fractious Greek poleis has marked a new era for both ancient and modern scholars. Following the defeat of Thebes and Athens at the battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC the squabbles of mainland Greeks would be eclipsed by the clash of empires. Two centuries of war had left the city-states of Greece shattered. Alexander the Great razed Thebes to the ground and imposed a Macedonian garrison on Athens. Sparta struggled for survival ever since Epaminondas had deprived her of more than 60% of her land and wealth by freeing Messenia after Leuctra (371 BC). He had also placed two ‘fetters’ on Sparta’s recovery by founding

two cities – Messene as the capital of Messenia, and Megalopolis (The Great City) just to the north of Laconia. Into this power vacuum in Greece, with the ever-present threat of Macedonia, two federations formed.

To the north of the gulf of Corinth, in mountainous Aetolia, a league of villages had coalesced into small cities. Aetolia did not have a strong agricultural base, and much of its wealth came from organised piracy. They had grown strong enough to defy Macedonia, with the help of Pyrrhus of Epirus, and became the dominant power in Northern Greece. South of the gulf of Corinth, the hitherto small league of Achaean towns, that had stood in Sparta’s shadow, began to grow around 280 BC Aratus of Sicyon expanded the League, to take in most of the Peloponnese except Laconia itself, and allied itself to Megalopolis. Outside Greece, in a few years, Hannibal would take on Rome, (218 BC) while Successor rivalry would pit the young Antiochus III ( later Megas, The Great) against Ptolemy at the battle of Raphia.(217 BC) Antiochus would eventually confront Rome at Magnesia (190 BC) and lose Anatolia/ Turkey as a result, as related in Ancient Warfare I-2.

Sparta returned to her traditional isolation in the Peloponnese after its hegemony was broken at Leuctra, and had not joined Thebes and Athens against Philip of Macedonia. Her intrigue with Persia to move against Alexander ended in crushing defeat. Their one victory against an heir to Alexander had been a defeat of the

invasion by Pyrrhus of Epirus and his death (272 BC). In 244 BC they suffered another disaster when the Aetolians overran Laconia and carried off, it was said, 50.000 men, women and children to be sold into slavery (the number is probably an exaggeration). What wealth there was continued to

accumulate to a rich few, including many women. A young and naïve King Agis proposed to return ‘to the old ways’. He proposed dividing the land up into cleroi (land estates) once more, 4,500 to go to landless Spartans and 15.000 to the Perioikoi (neighbouring Laconians). But there was a catch. Most of the land was heavily mortgaged. The wealthy naturally opposed any such land reform and Agis was murdered. His widow was forcibly married to the other King’s (Leonidas) son, Cleomenes.

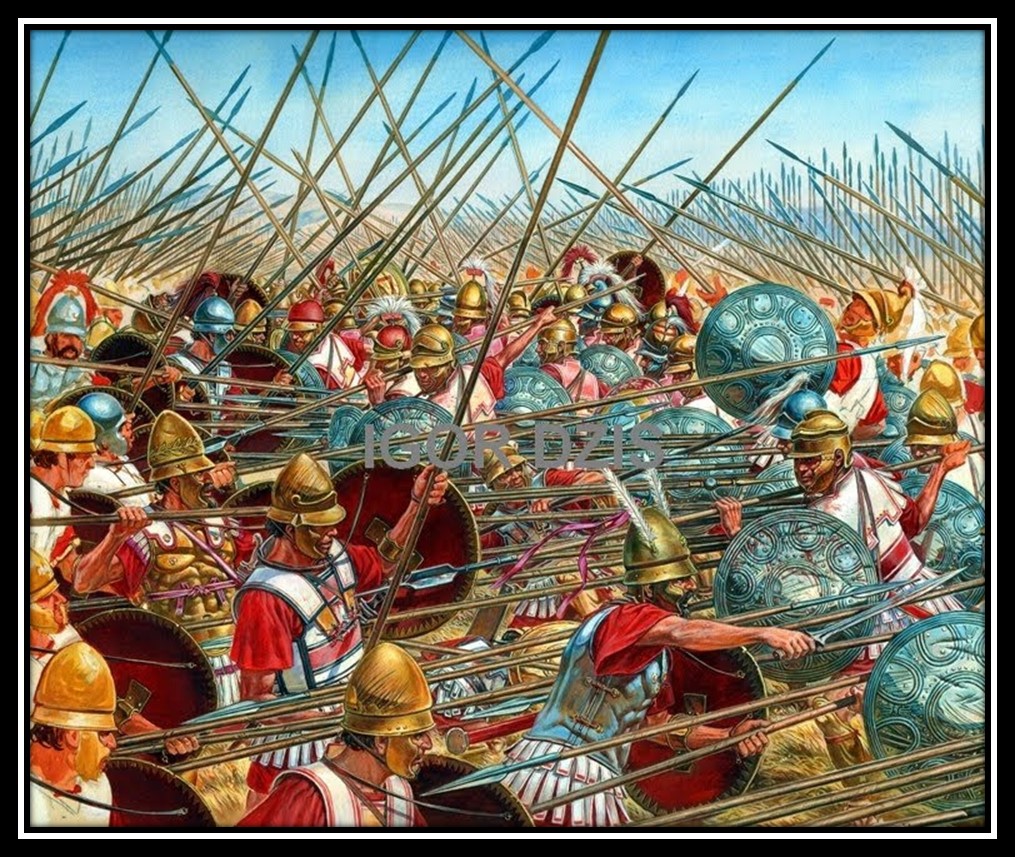

This had unexpected consequences. Cleomenes III coupled the vision of Agis with the ruthless efficiency of a tyrant and carried out reforms that were equally popular with the common folk and poor. He deposed and murdered the Ephors (ruling conservative elders), carried out land reform and parcelled out 4,000 new cleroi to Spartans and

Perioikoi, thereby raising again Sparta’s professional army, and equipped and trained this ‘new model army’ in the Macedonian fashion. His army grew, and with the addition of mercenaries, he could field 15,000 men. Ptolemy III of Egypt was funding Cleomenes secretly, to pay for mercenaries, in an effort to stir up trouble for his rival power, Macedon. This had a marked effect on the war which had been simmering on between Achaea and Laconia/Sparta since 227 BC and the Achaeans suffered three quick defeats (226 BC). Cleomenes nursed ambitions to make Sparta great again. The bourgeois of the Greek cities grew nervous at the thought of popular revolution, with Cleomenes as their champion, especially in Megalopolis and the Achaean League. With the reforms and the sudden increase in Sparta’s power, and the blows of the three successive defeats, Aratus, the Achaean leader, had two uncomfortable choices: fall under Cleomenes sway, or appeal for help to the Greeks hated enemy, Macedonia. He appealed to Antigonus Doson who promised help. His price was the return of a Macedonian garrison to the citadel of Corinth, which ironically had been ejected by Aratus. All the powers cast covetous eyes on Corinth and its strategic location.

We will look at the war and the campaign that led to this fateful battle in the next post.