1985: Sacred Oil Designer’s Notes,

by Fabrizio Vianello

Sacred Oil is the third and last module of the 1985 series. The first seed was planted in 2015, with a very detailed After Action Report of a The Next War campaign on my personal blog, WarWithoutKIA. Encouraged by the success, we started developing 1985: Under an Iron Sky and founded Thin Red Line Games a couple of years later.

Almost immediately, I found myself plunged in a world I’ve never dared to imagine: Grognards from all over the world were willing to help, militaries of every branch shared their knowledge on specific aspects of warfare. Some of them decided to dedicate considerable time and energy to our projects, growing our small initial team of two people.

Six years later, we are now at the final chapter. I had immense fun creating this trilogy, coupled with occasional moments of desperation, and I will miss it.

Now, back to business before the Gunnery Sergeant Hartman inside all of us starts wondering what my major malfunction is and if mommy and daddy didn’t show me enough attention when I was a child. And remember you may still reserve a copy by writing to info@TRLGames.com!

The Persian Gulf Trap

Besides the nature of the Soviet threat, U.S. strategists also had to consider certain aspects of the Southwest Asian theatre that closely affected American military capabilities. The major considerations – distance, lack of basing, and regional environment – must form the background to any discussion of general military strategy.

Concepts of Operations and Planning for Southwest Asia

RAND Corporation, 1984

According to a U.S. Department of Energy report, in 1985 36% of world oil production and 56% of world oil reserves were located in the Persian Gulf countries (Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates), so it’s easy to understand the interest that Western countries had in the region. On the opposite side, Soviet Union was an oil exporter, so its interest was not economic but strategic: denying the enemy access to a vital resource.

Despite its importance, the region in 1985 was mostly undeveloped, and a Soviet mechanized offensive against Iran would have faced three significant problems: Difficult terrain, poor or non-existing road network, and distances involved.

Deploying an appropriate defensive force would have been equally difficult or even worse for United States and its allies: The only available base in the area was Diego Garcia, a whooping 4000 km distance from the Strait of Hormuz, so access to airfields and ports had to be negotiated with the Gulf countries. Moreover, any heavy equipment should have been transported by sea.

Let’s talk about each problem more in detail.

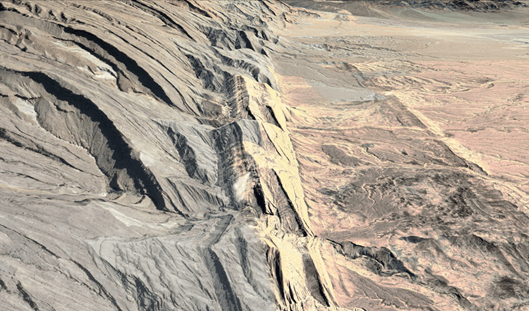

Terrain

From a cursory glance at a geographic map, Iran could appear as a more or less standard country, with a couple of imposing mountain ranges, ample plains and plateaus and a wonderful fertile area at the mouth of Shatt-El-Arab river.

Unfortunately, a closer examination reveals an almost alien region dominated by absurdly steep peaks, broken terrain, and salt marshes.

The Zagros mountains, starting in Northern Iran and ending at the Strait of Hormuz, is where the Eurasian and Arabian tectonic plates collided for millions of years and are still colliding now. They are on average only 1000 – 1500 meters higher than the Iranian highlands where they are rooted, so from an altitude point of view they would barely qualify as mountains.

Problem is, if you look at a detailed satellite image, you’ll discover they were probably designed and imported from Mordor. Except for selected mountain passes, moving anything across them is impossible.

Zagros Mountains, or Barad-Dur. Can’t remember.

The Eastern part of Iran is mostly covered by huge salt deserts, extending for hundreds of kilometres in all directions and with the occasional salt marsh thrown in for variety. In some areas, temperature in summer goes from 0° C at night to 70° C during day. Yes, that’s the highest temperature ever registered on Earth. Even today, it is practically an empty wasteland with barely any road.

The Eastern Great Salt Desert, near Tucson

Finally, the area where Tigris and Euphrates rivers enter the Persian Gulf is covered by the Mesopotamian Marshes, a salted wetland that in the period of our events was several times bigger than today. To give you an idea of how good this area is for conducting mechanized warfare, Iraq in 1984 stopped a dangerous Iranian offensive in this sector by releasing 200,000-volt electrical discharges into the marsh where the enemies were advancing in waist-deep water. Thousands of Pasdarans were electrocuted and drowned, and the Iranian attack failed.

Not everything is like a Martian landscape, though. Several areas around the main cities have extensive farming and decent roads, and are represented on the map by the standard, European style “Plain” terrain.

Transportation

According to CIA’s World Factbook, Iran in 1985 had 85,000 km of highways, of which 19,000 km paved. If you consider that Belgium in the same year had 51,000 km of paved roads, that Iran is 50 times bigger and is subject to harsh climate and seasonal floods, you’ll get the idea of how good the road network was.

Iranian rail network amounted to 4,000 km and was practically non-existent.

Alexis Seydoux helped us defining the details about roads. Alexis is a strange guy having, as far as I know, two completely unrelated fields of expertise: Electronic Warfare and the Islamic Republic of Iran, that he toured dozens of times for work. According to him, most of the Iranian highways become little more than trails when entering mountain areas and suffer from total lack of maintenance.

So, when the road you desperately need for crossing a mountain pass or tracing a vital supply line suddenly disappears into nothingness, right when you need it, you know what happened and who you should blame.

Distances

The distance problem actually has three different aspects, each one impacting one side or both.

Soviet Union is heavily impacted by land distances. A Soviet offensive starting from the Trans-Caucasian Military District must advance for approximately 1,400 km to reach the main objectives of the campaign – the Iranian oil fields and ports on the Persian Gulf. The greatest obstacle to overcome would have probably not been the Iranian army, but logistic: Soviet army would have confronted its own logistical shortages, guerrilla attacks on an Afghan scale or even bigger, and the more than likely US air strikes along the supply lines.

United States have a similar problem, but on sea. Except for US Marines MPSRON (Maritime Prepositioning Ships Squadron, more on this later), supply and equipment for high-intensity combat must be transported by sea from US West Coast. This could take up to 28 days and the danger posed by Soviet submarines must also be taken into account. A Mediterranean route could reduce the transit time to 16 days, but Suez channel could be sabotaged, and the convoys would be well within range of Soviet Tu-22 bombers taking off from the Black Sea.

Finally, both sides have a critical problem of distance from their air bases.

Soviet squadrons based in Trans-Caucasus, Turkmenistan or Afghanistan and flying within their normal Combat Radius (approximately 650 km) can barely support the first phase of the offensive. In order to have an air cover for the second phase and meet US air forces on (almost) equal terms, the Soviets need to take control of Iranian bases and make them operational for their aircraft.

Combat Radius from selected Soviet bases in Trans-Caucasus, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan

An alternate possibility for Soviet Union is persuading Saddam Hussein to concede access to Iraqi air bases. This would require keeping several transport squadrons busy shipping weapons to Baghdad and could backfire as the Americans would probably decide that an Iraq actively supporting Soviet Union in a war against United States cannot be tolerated.

Air bases are an even bigger problem for the US Coalition, as there’s initially none available in the region. Therefore, gaining the support of one or more Gulf states and bringing enough airfield to an operational status for US squadrons is an absolute priority.

Global Strategy for a Global War

A Soviet military move in the Persian Gulf region could have had several possible developments, depending by a multitude of factors. Deciding which options were the most probable, defining the possible actions for each option and writing the rules for each action was one of the most interesting aspects of the development.

The Communist Plan to Take Over the World

While recent events suggest that residual U.S. capabilities may be sufficient to deter Soviet adventurism, it would be foolish to base long-term policy on this assumption. […] It must be made clear that the U.S. feels its vital interests are engaged in the oil-producing regions of the Gulf, and that it is willing to take enormous risks to protect them.

The Soviet Threat to the Persian Gulf

RAND Corporation, 1981

In Kremlin’s plan, an attack in the Persian Gulf could have been conceived as a “limited” war to increase Soviet influence and weaken the Western countries, or as part of a global offensive to settle the score between Eastern and Western blocs once and for all.

Therefore, the first, secret dilemma that Soviet Union must face in Sacred Oil is about the strategic plan: The start date for Operation Baikal (the offensive against Iran) must be planned, and a decision must be taken about whether to execute or not Operation Ladoga (the offensive against NATO).

If Operation Ladoga is placed in stand-by, the offensive against Iran is the card on which the Politburo is betting to restore Soviet Union’s position in the world and the image of an unbeatable Red Army. In a few weeks, Iranian resistance must be crushed, the oil fields must be under firm Soviet control and Persian Gulf must be patrolled by Soviet aircraft.

Should the Politburo instead approve Operation Ladoga, the offensive in the Persian Gulf would become a secondary front having the objective of attracting as much US forces as possible there. Every American aircraft, ship and tank in Iran will be one less in Europe. Occupation of geographical objectives is still important, but secondary.

Another key decision for Operation Ladoga is timing: It should start before the growing international tension persuades NATO to mobilize, but preferably after the Americans committed significant forces to the defense of Iran.

On the US Faction side, the Soviet actions must be analysed to determine Kremlin’s real intentions. After all, Soviet Union had enough troops to mount an attack against Iran using only regional forces, and the attack could be the prelude to an offensive in Europe within days or even hours. Maybe a strong American reaction in the Persian Gulf, leaving fewer reserve forces available for the defense of West Germany, is exactly what the Soviets want.

Where is NATO When You Need It?

Without doubt, a Soviet offensive aimed at taking control of the Gulf region would have quickly escalated into a USA – USSR conflict, but not necessarily into a NATO – Warsaw Pact one.

The first and most evident reason is in NATO Article 5 and 6, already cited in the rules and summarized here below:

“The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all. For the purpose of Article 5, an armed attack on one or more of the Parties is deemed to include an armed attack on the forces, vessels, or aircraft of any of the Parties, when in the Mediterranean Sea or the North Atlantic area north of the Tropic of Cancer.”

Persian Gulf is not covered by the treaty, and it is not a question of mere detail. As any other treaty of this importance, every single word has been chosen carefully to ensure that only specific and well-defined events will be binding for the signing parties, and a war in Iran is not among them.

The second reason is that Soviet Union alone attacked Iran. The other Warsaw Pact countries attacked no one and invaded nothing. On what basis is NATO going to bombard East Germany or Czechoslovakia?

A practical example of this standard, unpleasant NATO inertia happened during the 1973 Yom Kippur war, when most of NATO countries refused overflight rights to US transports carrying supplies to Israel. Please note that we’re not talking about sending troops or declaring war to a superpower, but simply of giving overflight rights to aircraft of a long-standing ally.

This does not mean that no Western country except USA would have considered military intervention to defend its interests in the Gulf: France and Great Britain would have probably joined the US-led coalition since the start as they had the necessary force projection capabilities, active bases in the area, and the national support to the use of military force when no other choice remains. The other European countries in 1985 simply did not have neither the resources nor the political will for a significant intervention.

Also, the above does not mean that if the Iranian campaign were a Soviet victory everything would have returned to Business as Usual. USA and USSR are at war, the balance of power has been significantly altered and oil supply to Europe is threatened. A global military clash between the Soviet Bloc and the West would have been a possibility sooner or later, but not with the modalities and within the time frame covered by 1985: Sacred Oil.

For those convinced that a war between NATO and Warsaw Pact would have been certain at that point, I offer the following possible unfolding of events:

-

Soviet Union attacks Iran, United States intervenes. It’s war!

-

After weeks of heavy fighting, Soviet forces gain control of strategic locations in Iran and expel US ground forces.

-

Soviet Union offers a ceasefire, freedom of navigation in the Persian Gulf to commercial vessels, access to Iranian oil for any party willing to pay a price significantly lower than before, effective immediately.

-

European countries could now choose to declare war to Soviet Union. Unless the plan is an amphibious assault to Leningrad, this means attacking the Soviet installations in Eastern Europe and consequently declare war to the whole Warsaw Pact. The alternative is swallowing the bitter pill and continue buying the Iranian oil from the new Iranian puppet government. With a discount.

I think it’s a very good application of the old “Divide and Conquer” strategy.

The Unbearable Tension and Its Consequences

To deter or meet Soviet aggression, U.S. strategy calls for the rapid insertion of effective fighting forces into the area, relying upon measures as political agreements with regional states, host nation support, land and sea based pre-positioned materials, sealift, airlift, and highly mobile, heavily armed combat forces.

Concepts of Operations and Planning for Southwest Asia

RAND Corporation, 1984

One of the basic behaviours of Western countries during the late Cold War was the Proportionate Response doctrine.

In the early years of the USA – USSR confrontation, the almost complete nuclear supremacy allowed United States to adopt a simple, drastic approach to the communist problem: any Soviet aggression would immediately meet a strategic, unrestrained nuclear response, period.

As the Soviet nuclear arsenal increased and ultimately obtained a substantial parity, this simple and (ahem) reassuring policy gradually evolved into the Proportionate Response doctrine: Any countermove must be proportional to the threat, and the main objective was to deter Soviet Union from continuing that course of action, thus avoiding a military confrontation.

The Tension cards and rules reproduce the Proportionate Response doctrine, giving birth to the classical Cold War crisis development: Soviet Union or its proxies move some forces, United States reacts by sending comparable forces to the threatened region, and so on until one of three things happen: the crisis de-escalate, the area becomes a new “hot spot” with permanent forces of both sides, or war erupts. We’ve never seen the third possible outcome in practice, but this is what Sacred Oil is here for.

The Tension system also has three very interesting side effects.

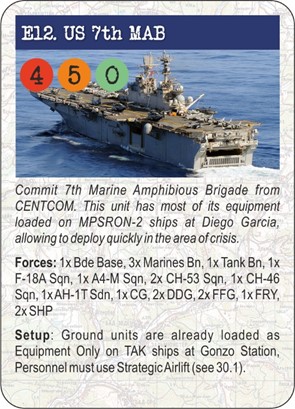

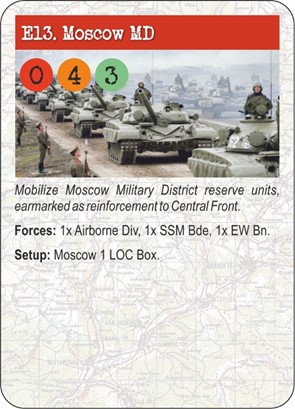

First, both sides will start the campaign completely unprepared for a large-scale military confrontation. Soviet Union sole forces in the region were 40th Combined Army, a little busy fighting Mujahedeen in Afghanistan, and Category II and III divisions requiring days or weeks to be combat-ready. On the opposite side, United States CENTCOM was still in its embryonal form and needs time to react to Soviet moves, obtain access to regional air bases, and move heavy troops in the area.

Second, no one really knows when war will escalate to a USA – USSR conflict. Soviet Union will of course know when hostilities against Iran will start, but depending by the strategic plan in execution the Soviets could wish to keep the Americans away as long as possible, or have them committing to war as fast and hard as they can. On the other hand, a particularly aggressive CENTCOM Commander could force Soviet’s hand into attacking the capitalist forces earlier than planned.

Third, neither side has a predetermined order of battle or reinforcement schedule. Both things must be decided by defining a plan, evaluating the enemy’s intention, and acting appropriately. US Coalition is more vulnerable on this, as the time needed to bring new forces to the operational theatre can be considerable, and after the start of hostilities there’s a concrete possibility that a Soviet submarine will sink them while in transit from CONUS.

Lines of Communication

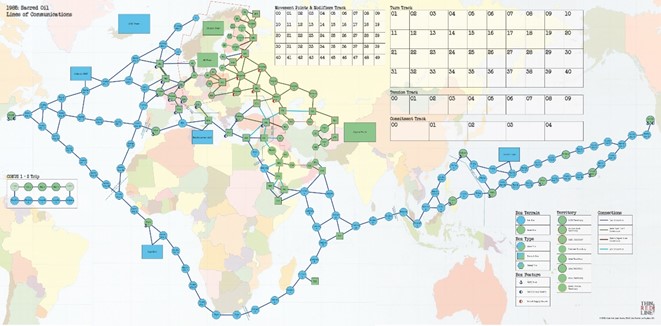

As last module of the 1985 trilogy, Sacred Oil must also work as a connection with its brothers, allowing to play a global, insane campaign spanning from North Cape to Strait of Hormuz and from Baghdad to Murmansk, at 14 km per hex. This glorious endeavour falls on the Lines of Communication Map.

The initial version of the LOC Map was significantly smaller and did not include the Pacific and Southeast Asia area. The first comment of Anthony Morphet after seeing it was “You’ve designed it in the wrong direction. We need the Pacific.”, but I babbled some defensive argument and kept it that way.

As the development went on, it became clear even to the most retarded (me) that a LOC Map without the Pacific area was cutting out a strategically important area and a big chunk of the fun – specifically, organizing the US convoys loaded with heavy equipment from CONUS to Diego Garcia, and avoiding the Soviet SSNs waiting for a prey.

The LOC Map was finally expanded to practically cover the whole planet, and this allows both sides to take decisions at strategic level and to connect the three different war theatres covered by the 1985 series.

The Lines of Communication Map in all its glory

US Faction may choose among three different possible convoy routes (Pacific, Atlantic or Mediterranean) for transporting supply to the Gulf region. This is a key decision as it allows to extend the supply network from the US to Southwest Asia; Without an active sea line of communication, all the US Faction forces in the Gulf would have to rely on supply delivered by ad-hoc air or naval transport missions.

Each route has a default level of Soviet threat, representing submarines and aircraft squadron not included in the OOB as they had different strategic assignments, but could have been used should a juicy opportunity target present itself. Moreover, Soviet Union may also decide to explicitly commit additional forces to the interdiction of each convoy.

As a side note, this version of the Designer’s Notes still needed some proof-reading. The final, proof-read version has been completed today and it’s better

Fabrizio – this is fantastic!! Thank you for all of the effort!!!

LOL send it to me I’ll swap it out.. dork

Hahaha!

That LOC map is fabulous. Insane, but fabulous. Just like the chutzpah of the whole series. Can’t wait to get my hands on it!

“Six years later, we are now at the final chapter. I had immense fun creating this trilogy, coupled with occasional moments of desperation, and I will miss it.” I will miss the anticipation of new modules as well (admittedly without the pain and frustration of having to make them!). But then again, you could always change your mind and do the Balkan theater as well. I would love to see that map and those armies in on the “fun” as well. Even if we had to assume that the USSR really did have all those forces we thought it did at the time…. Just a thought.

Someone on Facebook suggested to create smaller modules covering secondary fronts, or even completely different conflicts, using the 1985 system. I like the idea

How come I’m only learning that here – that’s work isn’t it?