Last week, I had the pleasure of visiting Singapore for a few days and I managed to visit a couple of war memorials and sites despite a bout with food poisoning. One of the most interesting places to visit was “The Battle Box”, an underground command complex built by the British in 1926 as part of the British Far East Command Headquarters. The “box” is a series of interconnected concrete tunnels and rooms built at Fort Canning Hill. It was used to coordinate the defense of Singapore and it was where General Arthur Percival decided to surrender Singapore to the Japanese on February 11, 1942. It was occupied by the Japanese until the end of the war and used primarily for communication.

The entrance is largely shrouded by vegetation and we nearly missed it on our walk. As you enter, a series of stairs takes you about 9 meters down where the cool air offers relief from the Singaporean heat.

The rooms in the Battle Box are small, cramped and dark. However, there is enough space under the hill to hold 26 rooms. I suspect there are other rooms that are located in the Battle Box that are not included on the official map as we were warned repeatedly to follow the directions provided and not to stray off the designated path. Indeed, there are one or two mysterious locked rooms that are off-limits to the public.

The first room is the telephone exchange room, featuring a British soldier frantically plugging in wires during the fall of Singapore as the Japanese army under General Yamashita approaches in early 1942. Sounds of battle overhead as well as shelling can be heard through the speakers in this room and give a general sense of the frantic activity that permeated the structure in those days.

Across the hallway is the office for the Fortress Commander and features a meeting between Maj. General Keith Simmons and Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival as they pore over intelligence reports and assessments from the nearby cipher room. Simmons, on the right, looks haggard and though he could be speaking, it looks more like a big yawn to me, as they work around the clock to try and salvage a hopeless situation.

Intelligence estimates of enemy troop strength and location appear on the wall of the cipher room.

The Gun Operations Room is located near the Fortress Commander’s Office and is where enemy aircraft information from Malaya and Singapore was passed and collected. Most of the information was from eye-witness reports who estimated the altitude of the aircraft. The information was then sent through to anti-aircraft gun crews to prepare them for approaching enemy raids or to divert friendly aircraft to intercept them.

The Commander of Fixed Defenses, Brigadier General A.D. Curtis, coordinates artillery strikes and the use of naval guns against Japanese targets. Many of the island defenses were focused on the south of the island where any attack was anticipated to be mounted. The Japanese attack from the north, however, meant that the naval artillery guns had to be turned to face inland where problems such as elevation and ammunition types resulted in their being less effective than hoped.

The Sergeant and Officers’ Mess room features a very basic serving area with some tea. The walls are lined with posters from World War II. In contrast to the rest of the rooms, this one is brightly lit and has a much less stifling atmosphere. It must have been a real relief to have some place for the men to relax considering the situation they faced above ground.

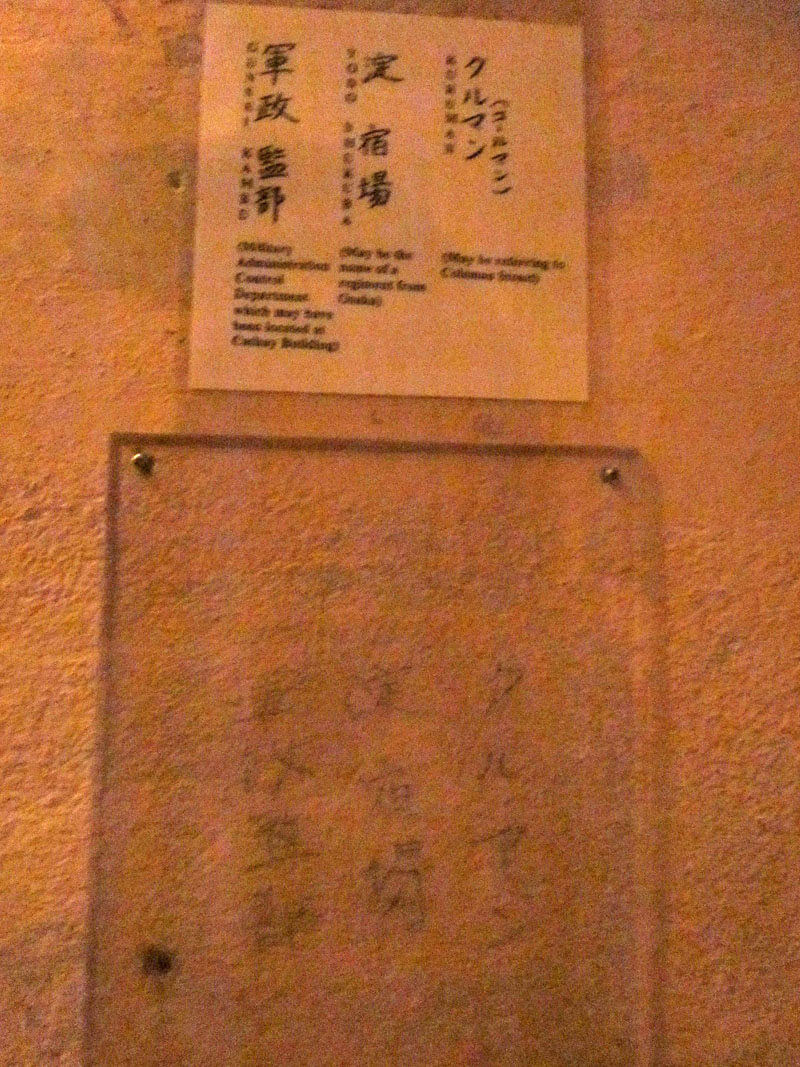

The final room of the tour features the Surrender Conference where Percival and the other British officers decided to seek terms with the Japanese in February of 1942. The Japanese held Singapore, which they renamed to Syonan, until their surrender in August of 1945.