Guadalcanal Campaign

7 Aug 1942 – 9 Feb 1943

Contributor: C. Peter Chen

Landing at Guadalcanal:

7 Aug 1942

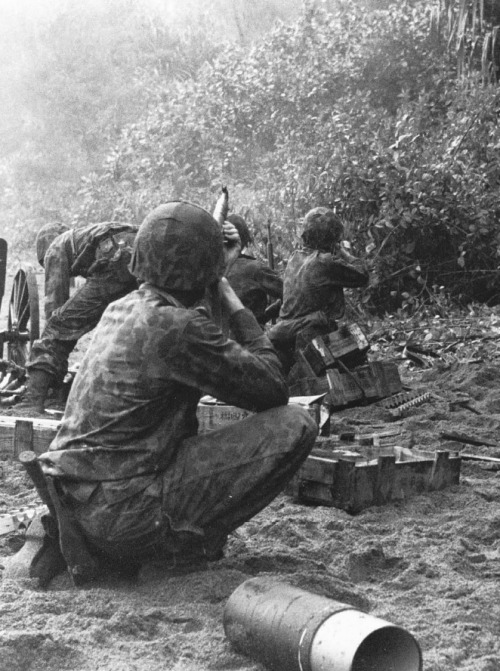

“Even before one drop of blood had been spilled on its fecund soil or a single corpse buried in it,” Dan van der Vat said, “Guadalcanal stank”. Even Morison, the US Navy’s own historian, used the self-coined word “faecaloid” to describe the humid jungle island. When asked about the conditions on the island, United States Marine Corps veteran and author William Manchester said “[m]ove a thousand yards inland. Just be sure you take a compass and leave a Hansel-and-Gretel trail behind you. If you don’t you will die.” Such was the awful conditions that Japanese and American men fought in.

Before the Japanese began constructing an airfield on Guadalcanal, the island was mostly ignored even by the Japanese occupiers. At the evidence of such an airfield being constructed, however, the mosquito and disease-plagued island, with the waters around it, soon became a hotly contested zone for the next six months. On 7 August 1942, the US First Marine Division landed on the island of Guadalcanal successfully albeit amateurish amphibious landing techniques (this was one of the first amphibious assaults in the war). The landers lacked information about the terrain, the tide, and the weather; some of the Marines were even wielding WW1-era rifles. On 0910 that morning, two battalions of the Fifth Marine Regiment established a 2,000-yard beachhead very quickly, and the airfield subsequently fell under American control. Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, the newly installed commander of the Japanese Eighth Fleet based at Rabaul, ordered an air assault on the Allied ships, but did not meet success. Mikawa then gathered every ship he could find and start sailing south.

Some days ago, Mikawa actually had already sent six transports filled with troops for Guadalcanal. While in transit, Meiyo Maru was attacked by American submarine S-38 commanded by Lieutenant Commander H. G. Munson, sinking her with a loss of 342 men. The rest of the transports turned back for Rabaul. Had this transport mission succeeded, the fight on the island of Guadalcanal would be much tougher for the American Marines.

The airfield was named Henderson Field after Lofton Henderson, a Marine pilot lost during the Battle of Midway.

The Japanese troops continued to shell the field with artillery, attempting to destroy or recapture the field. Bombers from Rabaul, despite constant Allied attack on that Japanese air field, were sent to attack Henderson as well. However, Allied engineers were able to keep the field available for aircraft to land and take off. Meanwhile, the American Marines slowly drove back the land elements of the Japanese forces on the island with superior firepower. The Americans held on to Henderson Field, but the Marines there felt helpless due to the lack of adequate naval support while the Japanese controlled the sea.

Battle of the Ridge / The First Battle for Henderson Field

12-13 Sep 1942

During the day on 12 Sep, the American Marines reported an unusual number of skirmishes with Japanese patrols, and Vandegrift prepared his forces for an attack. He formed his defenses at the area known as the Ridge 1,500 yards from Henderson Field. The Ridge’s close right flank was guarded by Marine engineers and pioneers, and the far right flank on the coast by Lieutenant Colonel Biebush.

The close left flank was guarded also by Marine engineers, and the far left flank at Tenaru River by Lieutenant Colonels Pollock and McKelvy. The Japanese, under the command of General Kiotake Kawabuchi, attacked after nightfall.

Biebush, Pollock, and McKelvy fended off the secondary attacks amongst Japanese yells of “banzai!” and “Maline (sic), you die!”, but the main thrust at the Ridge was a different story. Japanese troops charged the Ridge wave after wave with grenades, rifles, and bayonets, with each wave signaled by red flares which attracted attention from American mortars. During the battle, salty exchanges of “US Maline (sic) be dead tomorrow!”, “Hirohito eats shit”, and “Eleanor eats shit” were heard in between bursts of machine gun fire.

Throughout the night, the fearless Japanese attackers charged and charged, pushing the Marines to the last knoll of the Ridge. If the Japanese could push the Marines off of the last knoll, then there would be no further natural obstacles defending Henderson Field.

The Marines held.

The last charge took place at dawn, and after that charge the Japanese offensive ceased. The Marines noted that the Ridge was “littered with Japanese bodies sprawled in the pitiful and repulsive attitudes of death.”

As American aircraft took off and strafed remaining Japanese units still in the area, the Marines buried 40 of their fallen comrades and treated the 103 wounded. The Japanese casualties were much greater.

Out of the 2,000 troops committed on this night offensive, over 800 were killed in battle (200 reported by McKelvy, 600 reported by Colonel Edson at the Ridge), and hundreds more died of their wounds on their retreat to the coast. By the end of Kawaguchi’s campaign, he had little over half of the 3,450 troops he had at the time he landed on the island.

From the World War II Database www.ww2db.com

2 thoughts on “Background of Bloody Ridge @ Guadalcanal /3”

Comments are closed.